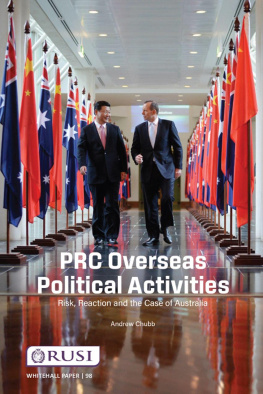

PRC Overseas Political Activities

Risk, Reaction and the Case of Australia

Andrew Chubb

www.rusi.org

Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies

PRC Overseas Political Activities: Risk, Reaction and the Case of Australia

First published 2021

Whitehall Papers series

Series Editor: Professor Malcolm Chalmers

Editor: Dr Emma De Angelis

RUSI is a Registered Charity (No. 210639)

Paperback ISBN [978-1-032-15207-3] eBook ISBN [978-1-003-24303-8]

Published on behalf of the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies

by

Routledge Journals, an imprint of Taylor & Francis, 4 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon OX14 4RN

Image Credit: President Xi Jinping with Australias Prime Minister Tony Abbott at Parliament House in Canberra, November 2014. Courtesy of Reuters/Alamy Stock/ Lukas Coch

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Please send subscription order to:

USA/Canada: Taylor & Francis Inc., Journals Department, 325 Chestnut Street, 8th Floor, Philadelphia, PA 19106 USA

UK/Rest of World: Routledge Journals, T&F Customer Services, T&F Informa UK Ltd, Sheepen Place, Colchester, Essex, C03 0LP UK

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Contents

The author gratefully acknowledges support from the Columbia Harvard China and the World Program and the Lowy Institute during this research project, and Emma De Angelis, Malcolm Chalmers, Veerle Nouwens, Zenab Hotelwala and the editorial team at RUSI. For helpful comments on earlier drafts, thanks in particular go to Geremie Barm, David Brophy, David Campbell, Jie Chen, Tom Christensen, Mary Lynn de Silva, Gerry Groot, Ash Jones, Wendy Leutert, Darren Lim, Adam Ni, Alex Oliver, Charles Parton, Richard Rigby, Matthew Robertson, Wanning Sun, and all anonymous reviewers. Thanks are due also to those who kindly took the time to share their thoughts and ideas in formal interviews and informal conversations since the projects inception in 2017. The author takes sole responsibility for all shortcomings, errors and omissions.

Andrew Chubb is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow based in the Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion at Lancaster University, where he researches the linkages between Chinas domestic politics and international relations. A graduate of the University of Western Australia, his current project focuses on the role of domestic public opinion in international crisis diplomacy in the Asia-Pacific. More broadly, Andrews interests include maritime and territorial disputes, strategic communication, political propaganda and Chinese Communist Party history. His recent research articles can be found in International Security, International Relations of the Asia-Pacific and Asian Security.

The emergence of the Peoples Republic of China (PRC) as a global power has reanimated a central challenge for liberal democracies: how to protect both national security and political liberties when adversaries are willing and able to use one against the other. In President Xi Jinpings New Era of PRC power, politicians, pundits and the media in the UK, the US and Australia are paying increasing attention to the overseas political activities of Beijing and its supporters. Many such concerns are well founded. Covert and overt political activities are in the Leninist DNA of Chinas ruling party; communications technology has created new opportunities for authoritarian regimes to suppress dissent beyond their borders. On top of this, pro-Beijing patriots and wealthy lobbyists are advancing their views with increased confidence, and many influential economic actors involved in trade relations with China share significant overlapping interests with its party-state. Yet the need for policy responses to these developments also raises a further set of risks from within liberal democracies. These range from the polarisation of public discourse and the rise of alarmist rhetoric that fans xenophobia and harms social cohesion through to legislative encroachments on civil liberties and growing powers of national security agencies that operate with limited public oversight.

Such dilemmas are not new. The onset of the Cold War in the mid-20th century prompted painful choices and numerous missteps in liberal democracies. In the US, claims of widespread communist infiltration and subversion led to McCarthyist political inquisitions and purges, along with legislation later deemed unconstitutional.1 The UK and Australia both saw a major expansion in the largely unaccountable powers of security agencies that historians have argued generated little useful intelligence.2 Since the 1990s, and particularly after 2001, the ability of transnational terrorist groups to inflict mass fatalities and potentially acquire weapons of mass destruction prompted radical new security measures that encroached significantly on civil liberties and had debatable effectiveness in reducing the threat.3 Most recently, in the age of social media, democracies have struggled to counter Russias attempts to influence electoral processes, co-opt elites and suppress dissent by migrs.4 The overseas political activities of the PRC and its supporters present another expression of the ongoing challenge of protecting national security and democratic freedoms while preventing their abuse.

Debates on these policy dilemmas often frame liberty and security as being in tension, with an increase in one held to warrant a decrease in the other.5 Yet recent experience has shown this assumption of inherent tradeoffs does not always hold. During the Cold War, Australian security agencies mistakenly perceived causal linkages between foreign communism and activism on a wide array of issues from Aboriginal rights and immigration policy to South African apartheid and the Vietnam War leading to both encroachments on political freedoms and wastage of national security resources.6 Post-9/11 attempts to strengthen national security have produced avoidable side effects affecting both liberty and security. Inflammatory political rhetoric on terrorism, for example, has undermined the government-community relations upon which effective security intelligence depends.7 Sensationalist media and public commentary have stoked social division and Islamophobia by presenting Muslim communities as problem populations, while also amplifying the sense of insecurity and mistrust among citizens more broadly. These experiences have highlighted the critical importance of the language and framing terminology used in policy debates, the need to draw sound analytic distinctions between issues, and the potentially harmful influence of elite political rhetoric and media coverage on the prospects for methodical, evidence-based public policymaking.

This paper examines the array of challenges the PRCs overseas political activities have presented to liberal democracies, as well as the significant risks involved in responding, drawing primarily on Australias experience with both. This makes sense for two main reasons. First, Australias regional proximity and relatively high level of economic and people-to-people engagement with the PRC have ensured a wide array of detailed examples are available, rendering many complex issues amenable to focused analysis. Second, since 2017 Australia has carried out an intense public policy debate on these issues, and Canberra has launched a series of policy initiatives accompanied by heavy publicity. These responses have been hailed internationally as a trailblazing model for countering foreign interference. Domestically controversial, Australias policy responses have so far received little critical evaluation outside the country. This paper argues that Australias experience offers cautionary lessons for other China-engaged liberal democracies.