Copyright 2003 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Common-wealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-2281-6 (cloth: alk paper)

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Member of the Association of

American University Presses

Preface

In my central Kentucky hometown, the Civil War is still part of the fabric of life. A cannonball is deeply imbedded in the brick wall of a store in the town square, a mute reminder of a brief visit paid by John Hunt Morgan in the fall of 1862. Lincolns Birthplace National Park stands only fifteen miles from the house where I grew up; I remember thinking, even as a child, how odd it was to be commemorating a dirt-poor Kentucky farm boy by building a marble temple around a crude log cabin. I was accustomed from an early age to seeing images of Lincoln everywhere, and among my earliest memories are my grandfathers stories of a vague, shirttail relationship to the Emancipator president himself; I never understood exactly what. And yet, travel fifteen miles from my hometown in another direction, and it was never difficult to find stickers carrying the image of the Confederate battle flag, on sale in the convenience marts between the cheap sunglasses and the decks of cards.

The Civil War is a living thing in Kentucky.

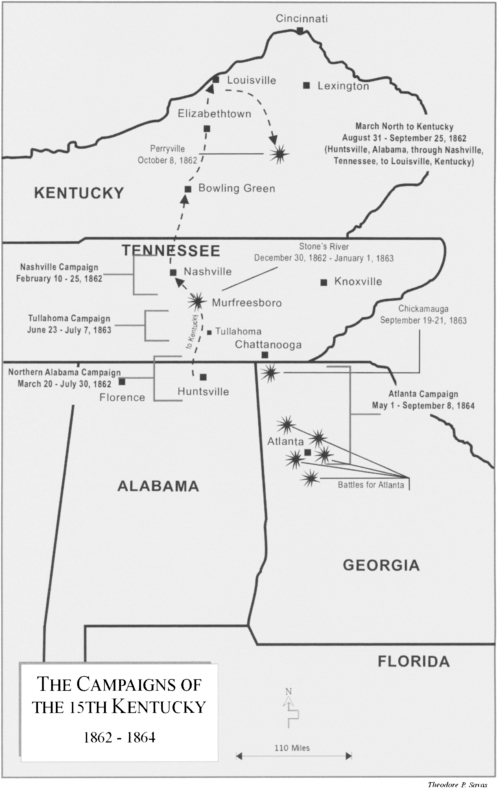

While I was in college, far from home, I began in an unfocused way to research family history. I had known for years the stories about my three-great-grandfather, a young captain killed fighting for the Union at Stones River. As I worked, I discovered more and more stories, but they all seemed to lead back to the same place, like spokes of a wheel. Capt. Smith Bayne, it turned out, had two brothers, both in the same unit. Cousin after cousin turned up in the old documents, but nearly all of them turned out to be members of the same Union regiment, the Fifteenth Kentucky Infantry.

Among most Kentuckians who think often about that war, the Confederacy is very much our side. Alistair Cooke called Kentucky the most self-consciously Southern of all the states, and bias among students of the war in Kentucky tilts toward the Confederacy by at least a five-to-one margin, perhaps double that. So it was a real surprise to find a band of Kentuckians fighting for the Union while tramping around old family pictures and documents, and I began to wonder what sort of people these were and what their story had been.

Regimental histories were the first commentaries on the war. Some written in diaries and on scarce letter-paper by firelight in the camps and on the battlefields, others written not long after the war, the men wrote of their experiences and tried to come to grips with what it had all meant. Historian Earl J. Hess has divided this large band of soldier-writers into four groups: the soldiers who continued to see the war in starkly ideological terms; the lost veterans, who most vividly remembered the horrors of battle and saw nothing redeeming in the war; the pragmatists, who rejected political ideologies but saw the war as a crucible of mens characters; and the nonpolitical veterans, who chose to emphasize the comradeship of the wartime experience.

After the veterans had slowly passed from the scene, history from the viewpoint of the private soldier became less fashionable; and so it was until the middle of the twentieth century, when historian Bell Irvin Wiley published a pair of classics, Life of Billy Yank and Life of Johnny Reb. Only twenty years ago, another revival began, led off by an unusual book in which Michael Barton applied the techniques of content analysis to a sampling of Civil War letters to investigate the character and values of Civil War soldiers. Most of the books since have not followed where Barton led; rather, subsequent historians have been interested in the soldiers attitudes toward the experience of battle and the political issues of the war. This trend includes the work of Gerald F. Linderman and Randall C. Jimersen, two books by Reid Mitchell, and two by James McPherson, who painstakingly read thousands of soldiers letters to produce two modern landmarks, What They Fought For and For Cause and Comrades.

At the same time, both professional and amateur historians moved to fill the gaps left by the veterans, publishing histories of dozens more Union and Confederate regiments. These books ranged from traditional regimental histories, such as Warren Wilkinsons history of the Fifty-seventh Massachusetts and Richard Moes book on the First Minnesota, to newly discovered veterans manuscripts such as A Southern Boy in Blue, edited by Prof. Kenneth W. Noe. A recent book that considers many of the same issues as the modern regimental histories from an army-wide perspectivein addition to filling a gap in the literatureis Gerald J. Prokopowiczs All for the Regiment: The Army of the Ohio, 186162.

But in all this extensive literature on the private soldiers experiences, there has been relatively little attention paid to the large number of Kentuckians who fought for the Union. During the veterans generation, the literature on the Fifteenth Kentucky is limited to an article in a short-lived veterans magazine by the units adjutant. Within the last generation, aside from Professor Noes book, only one of Kentuckys fifty-five infantry and seventeen cavalry units has attracted the interest of a historian.

The oversight is difficult to understand. Kentucky contributed 79,025 men to the Union army for service in the field, and another 12,476 Kentuckians served in Home Guard units, guarding lines of communications and chasing guerrillas. More Kentuckians volunteered for the Union army during a two-month period in 1861 than went south during the entire four years of the war, and this in a state that offered no bounties to its Federal volunteers.

The story of the Fifteenth Kentucky Infantry, the frequently ill-starred outfit that Gen. William S. Rosecrans once called his Orphans, stands out among this abundance of lost history. The Fifteenth served for three years, organizing at the Fair Grounds in Louisville in the fall of 1861 and serving until the winter of 1865, when the war was nearly won. Only thirty-two regiments in the entire Union army lost a greater percentage of their men in battle, and the Fifteenth had the highest casualty rate of all among the Fourteenth Army Corps, the principal Union army in the western theater.