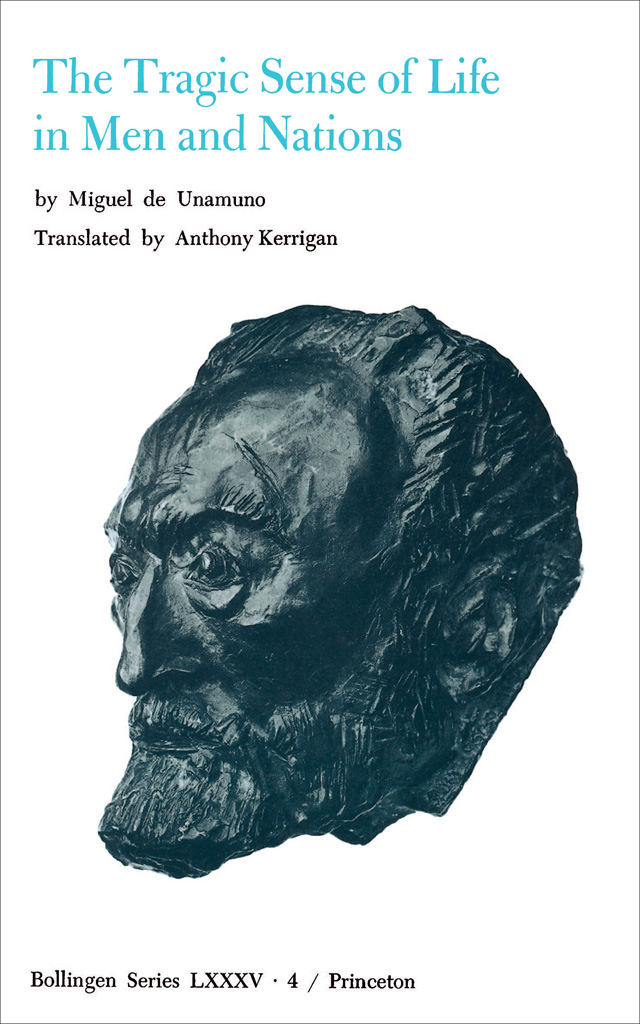

BOLLINGEN SERIES LXXXV

Selected Works of Miguel de Unamuno

Volume 4

Edited and Annotated by

Anthony Kerrigan and Martin Nozick

Miguel de Unamuno

The Tragic Sense of Life

in Men and Nations

Translated by Anthony Kerrigan

With an Introduction by

Salvador de Madariaga

and an Afterword by

William Barrett

Bollingen Series LXXXV 4

Princeton University Press

Copyright 1972 by Princeton University Press

All rights reserved

Library of Congress catalogue card no. 67-22341

ISBN 0-691-01820-0 (paperback edition)

ISBN 0-691-09860-3 (hardcover)

eISBN 978-0-691-22574-6

First PRINCETON PAPERBACK printing, 1977

Fourth paperback printing, 1990

R0

Translator's Foreword

The Tragic Sense of Life in Men and Nations is the Great Pine, the Attis-Adonis pine tree, of Miguel de Unamunos work. It is also an Amanita (whose host tree south of the forty-fifth parallel is ultimately the pine, as Pliny held), an Amanita muscaria, the deadly mushroom which killed Claudius (administered with the help of the Spanish philosopher Seneca, as Robert Graves has submitted), a dangerous cultivation but also a spontaneous growth identified with lightning and the divine poison of sacred madness. Unamuno meant to plant the poison of doubt; but from the mature plant he expected the fruit of belief to grow. He sowed the same seeds elsewhere, everywhere, but this potent tree took the strongest root.

Closely related seeds for this particular specimen of thought, of a book, the cousin-german seeds, are to be found scattered in the Diario intimo, the keeping of which saved him from the temptation of suicide (as Unamuno wrote Dr. Gregorio Maranon). The diary was locked away and is just now first published in Spain (three distinct editions, 1970-1971) after being unpublished and out of sight (indito even in Spanish), for some 70 years: a secret and mostly spiritual diary. (All this time it has been kept under lock and key in a standing roll-front wooden cabinet in his workroom in Salamanca.) The Diario was an adumbration and served as a preliminary sketch, twice removed, for The Tragic Sense of Life: the conflict between asserting heart and denying reason, with Unamuno physiologically requiring belief in continuity of self. The coincidental point of departure in time for the Diario was the evolution, or disintegration, of one of his children, a mere babe in a crib who slept by his side, blasted by disease and growing up retarded, thus bringing into question, close to home, the whole of Creation. The first word in the Diario is the Greek for hydrocephaly, and it serves by way of epigraph. A real-life event would be the natural fodderyes, fodder, in this case: psychic straw, hayfor Unamunos mind. He lived in the flesh as all other men must, but he also lived in the flesh spiritually, as a whole man, nada menos que todo un hombre, altogether a man; a seminal father and no Spanish Don Juan, his natural adversary, whether in life or literature; a thinking life-sized entity, and no thinking reed, like Pascals man, the weakest in nature; an all-around polemical thinker, and no objective pedant, no mere professor, not a savant at all, as he repeatedly proclaimed. The opening chapter of our book is titled The Man of Flesh and Blood, and it was as such a man that he considered and meditated mans fate. (It must be admitted, though, that Unamuno considered Don Quixoteand Don Juanto be as real as Cervantesand Tirsoand the characters in his own fiction as alive as himself.)

Perhaps no other thinker ever conceived his greatest book on the basis of such a phenomenon: an imperfect child, a human, all-too-human, mis-conception.

If he, as father, had created a permanently imperfect thing, it was only to be expected that the Father of Creation was directly involved. (The last full entry, dated January 15, 1902, in the Diario intimo, is a Padre nuestro of Unamunos own composition, which reads, cryptically: Father always engendering for us the Ideal. I, projected to an infinity, and you, projecting yourself to infinity, meet; our parallel lives meet in infinity and my infinite I is your I....). He also thought he himself might be to blame. His faith was by now dubious; and ReasonReason in religion was a plague. It was the principal cause of his downfall. (For the Diario includes no questioning of tradition; quite the contrary: it is an almost compulsive devotional, an evocation of given Belief. Unamuno fell back on the reactions of his infancy, of a primitive infancy, of the infancy of his Basque people and of Christian Europe.) In a letter to the novelist Leopoldo Alas, a bare half-year before the birth of the doomed boy, he wrote: My faith in an intimate, organic Catholicism, wellspring of reflex actions, is precisely what turns me against it when it is concretized in formulas and concepts. And to the same correspondent he had spoken of a proposed fictional character (much like himself, he noted) who, since he carries God in the marrow of his soul has no need to believe in Him: it is a reflex action.

Few thinkers in history-as-written-down must have taken as point of departure for their thinking their condition as fathers; a few have thought as Fathers, as Fathers of the Church, or simply as Fathers in the Church, but their thinking has been necessarily disembodied. In any case, Spinoza and Kant and Pascal were bachelors; they were never, apparently, fathers; and neither were they monks in the Christian sense of the word. Yes, and (Unamuno characteristically does not mind repeating himself): Spinoza was, like Kant, a bachelor, and may have died a virgin.

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo de Larraza (or U. Jugo de la Raza, as he called himself, as author, in Cmo se hace una novela, a name which translates as U. Marrow of the Race), Unamuno-even if he must have conducted himself in the sexually abstracted manner of his total opposite, Valrys Monsieur TesteUnamuno y Jugo de Larraza y Unamuno (to give him his full set of surnames in Spanish: twice an Unamuno) was no virginal non-begetter.

This thinker of the living (and dying) thought was Rector-for-Life of the University of Salamanca, and he was, naturally enough in Spain, removed: three times in all. The first time he was removed (on orders from Madrid), he never learned the reason why. After his reinstatement, he was again removed, by the Republican government in Madrid on August 22, 1936; then alsothus making him a total outcast banished by both camps in the Civil Waron October 22, by the other side, the Nationalist government (and this time by his own colleagueshis fellow professorsa fact often forgotten, as Emilio Salcedo points out in his lovingly detailed journalistic biography of Unamuno): Azaa signed the decree, as President, for the Republic, expelling Unamuno from the University and forbidding him to act in any capacity; exactly two months to the day later, Franco signedthis time at the behest of the University council of professorsa similar decree. Victim-by-association of all these decrees, these official curses, Unamunos Rectors House (Casa Rectoral) has never again been officially occupied, has remained unoccupied by any other rector since Unamunos death on the last day of the first year of the Spanish Civil War: kept open (and now declared National Patrimony, not to be touched except by some higher authority) as if for him, with his brass bed and his books (and his antique washbowl, too) intact and in place, as if awaiting his returnin the flesh.