Contents

Guide

List of Figures

Pagebreaks of the Print Version

ALSO BY YING ZHU

Soft Power with Chinese Characteristics: Chinas Campaign for Hearts and Minds

Two Billion Eyes: The Story of China Central Television

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema

TV China

TV Drama in China

Television in Post-Reform China: Serial Dramas,

Confucian Leadership and the Global Television Market

Chinese Cinema During the Era of Reform: The Ingenuity of the System

Hollywood in China

Behind the Scenes of the Worlds Largest Movie Market

Ying Zhu

NEW YORK

LONDON

For my mother and my daughter

Contents

INTRODUCTION

From Paris Theater to Huaihai Cinema: As the Cinematic Universe Turns

In March 1922, Mingxing (Star/Bright Star), a newly established Chinese film studio, set up its corporate headquarters at No. 380 Avenue Joffre, in Shanghais French Concession. Named after Joseph Joffre, the French general best known for defeating the German invasion during the First World War, Avenue Joffre was a tree-flanked residential street in suburban stylelined with row houses and dotted with churches, cemeteries, schools, parks, coffeehouses, cafs, and cinemas instead of businesses and factories. On Avenue Joffre, as one local jazz aficionado observed at the time, there are no skyscrapers, no especially large structures, but every night there are the intoxicating sounds of jazz music coming from the cafs and bars that line both sides. With a headquarters situated in such a trendy location, it is no surprise that Star would soon become one of the dominant players in Shanghais flourishing movie industry in the 1920s and 1930s.

I spent part of my childhood a short walk from Stars headquarters, in a courtyard complex, Joffre Arcade, built in 1934 by the St. Petersburgborn Russian architect and builder Boris Krivoss, who left Russia for China in 1921. The complex had flats lining up on two sides of an open courtyard with a circular fountain in the middle, which became a frequent playground for me and the neighboring kids.

Also on Avenue Joffre, a few doors up from my childhood home, at No. 550, was the Paris Theater, a legendary movie house that was the setting of a well-known 1931 short story by Shi Zhecun, a pioneer of Chinese modernist literature. At the Paris Theater depicts a night out on a movie date between a married man and his mistress, capturing the jitters of a titillating extramarital affair. Never mind that the Paris Theater was actually contracted to screen Hollywood films, which by the late 1910s had swept the Chinese market. So popular was Hollywood in China that when the Chinese film industry took its initial shape in the 1910s through the 1920s, it simply followed the Hollywood-style production practice including the studio model. While mesmerizing local audiences and theater owners, Hollywood also encountered resistance from local cultural elites who fretted about vulgar entertainment from time to time.

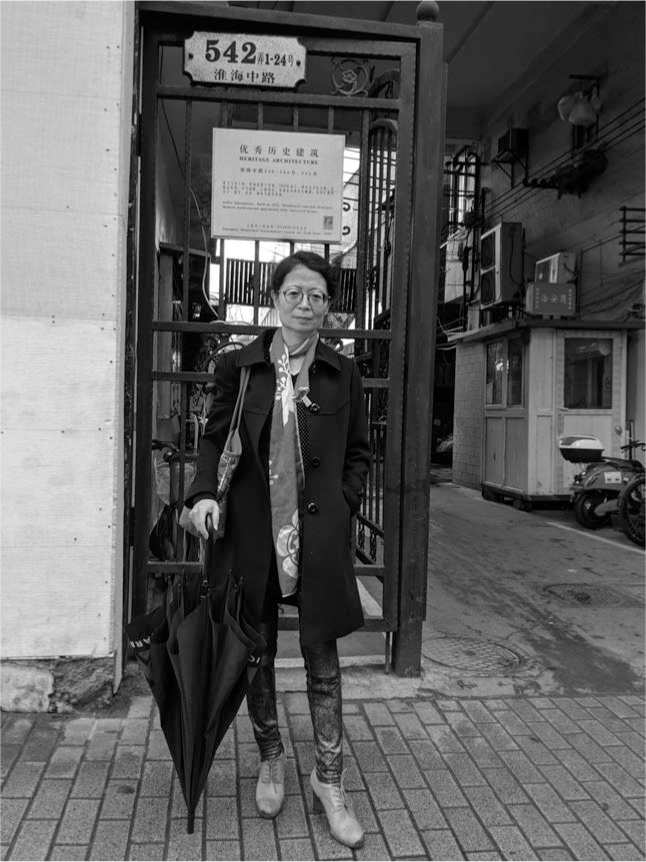

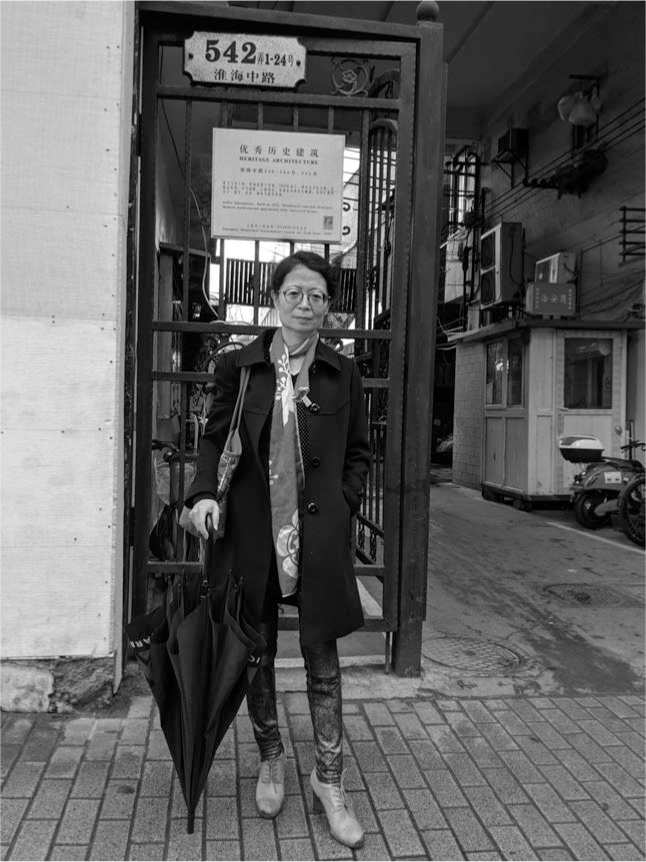

The author in front of her childhood home next to the Paris Theater. Courtesy of Frances Hisgen.

Built in 1926 by a Shanghai merchant, Ding Runyang, the Paris Theater began life as the Palais Oriental Theater at its debut in May. In January 1927, the Palais Oriental signed a contract with Peacock Motion Picture Corporation (Peacock), the earliest and largest Sino-U.S. joint venture at the time, to screen films distributed by Peacock.

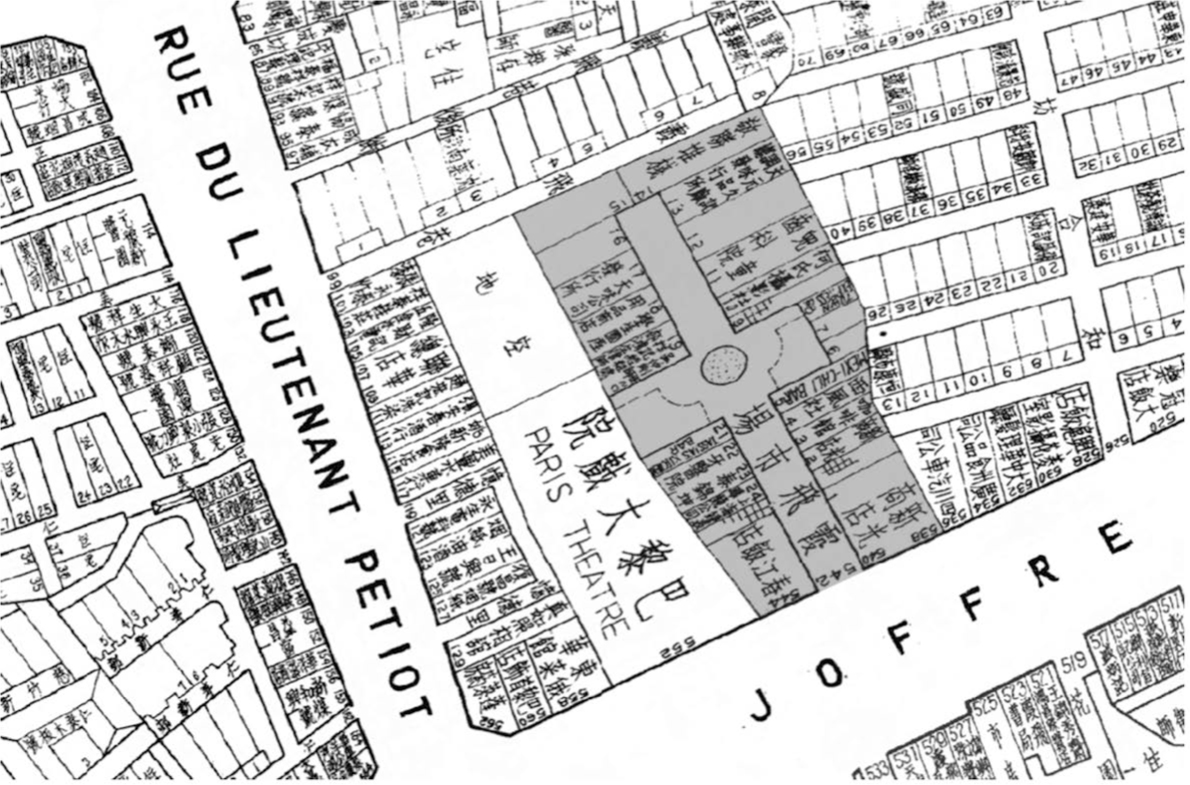

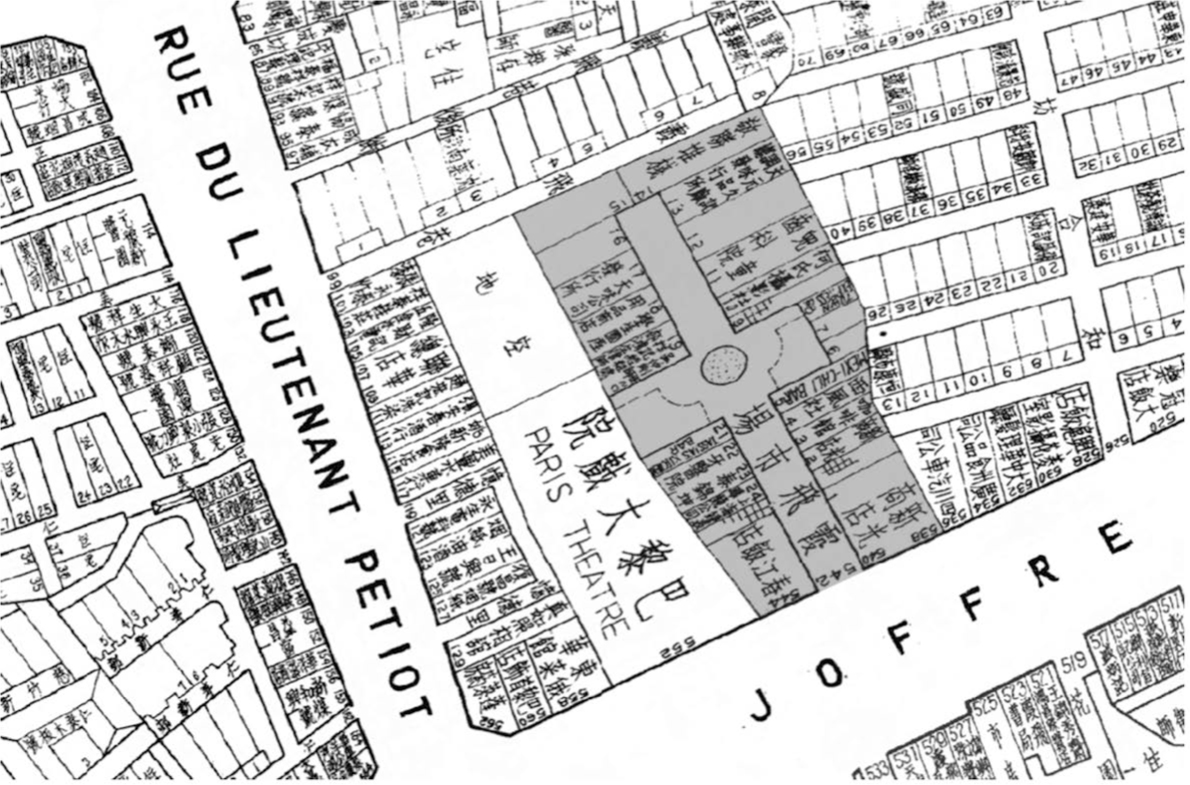

Map of Joffre Arcade. Source: Shanghai Commercial Atlas (1939). Shading by Katya Knyazeva.

With the translation of the Hollywood film the Toll of the Sea (Chester Franklin, 1922), Peacock initiated the trend of adding Chinese subtitles to imports. During its peak between 1926 and 1931, Peacock signed exclusive rights with major U.S. studios and was instrumental in importing a number of quality Hollywood titles.

The Paris Theater would change its name again in 1951, to Huaihai Cinema, following the renaming of Avenue Joffre to Huaihai Road the same year, striking out the colonial imprint on the city and instead commemorating the Huaihai Campaign, or Battle of Hsupeng, a decisive Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War.

Whatever the banner it was under, the theater became my madeleine of early cinema going. I had my share of movie dates there, though the young dates of my adolescence were far more innocent than the lascivious man leering at his mistress in Shis fictionalized universe. And I had no discerning taste when it came to foreign films, which were few and far between. When there was a foreign screening, it was mostly revolutionary pictures from the USSR and the affiliated Eastern Bloc, including India, North Korea, and Vietnam. UFA and Hollywood pictures were long gone by the time I came of age during the Cultural Revolution (196676).

The post-1949 transition from Hollywood entertainment to Soviet revolutionary pictures took time. The Communist government aggressively promoted Soviet films, but the Hollywood-addicted Shanghai audiences did not take well to the pictures from the USSR. To maintain social stability, the new municipal government tolerated a few Hollywood films still in circulation to provide comfort and much needed distractions to the jittery middle class unsure of its future under the CCP. Hollywood served briefly as opiate of the masses, to quote Marx, albeit under Shanghais Communist leadership.

The outbreak of the Korean War would cast a decisive end to Hollywoods early sojourn in China, leading to a wholesale ban on all things American including Hollywood pictures. The party swiftly moved to rid Chinese screens of all remnants of Hollywood films. A massive campaign was launched to discredit Hollywood films, equating watching American films with unpatriotic and counterrevolutionary activity. The Paris Theater severed its ties with Hollywood with a bang on November 10, 1950, when patriotic employees draped a big banner of Resisting American Films over its building. The day after the Paris Theaters grand gesture, the Shanghai Movie Theater Association called for an emergency meeting to hash out a plan to halt the screening of American films. By November 14, all theaters in Shanghai had stopped screening American films, and the Chinese film industry itself would soon enter a period of radical transformation. Run entirely as a private and commercial entertainment business during the Republic era, the industry had to adopt a centralized Soviet model under the CCP, which treated film as an instrument for carrying a political torch for the party.

Parade along Middle Huaihai Road in the 1950s. Source: Collection of Shengkai Li.

The ban on Hollywood would last throughout the Mao era (194976), during which domestic socialist films and revolutionary films from the Communist Bloc were the staple screeners for Huaihai Cinema. Yet there was no shortage of Hollywood films and films from Western Europe, which were all lavishly dubbed in Chinese. But these Western films were reserved as internal reference films, open for viewing only to the partys top echelon under the direct control of Madame Mao (the wife of Chairman Mao), the local party