The Complete Works of

ANTIPHON

(480-411 BC)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2022

Version 1

Browse Ancient Classics

The Complete Works of

ANTIPHON OF RHAMNUS

By Delphi Classics, 2022

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Antiphon

First published in the United Kingdom in 2022 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2022.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 80170 068 9

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

The Translations

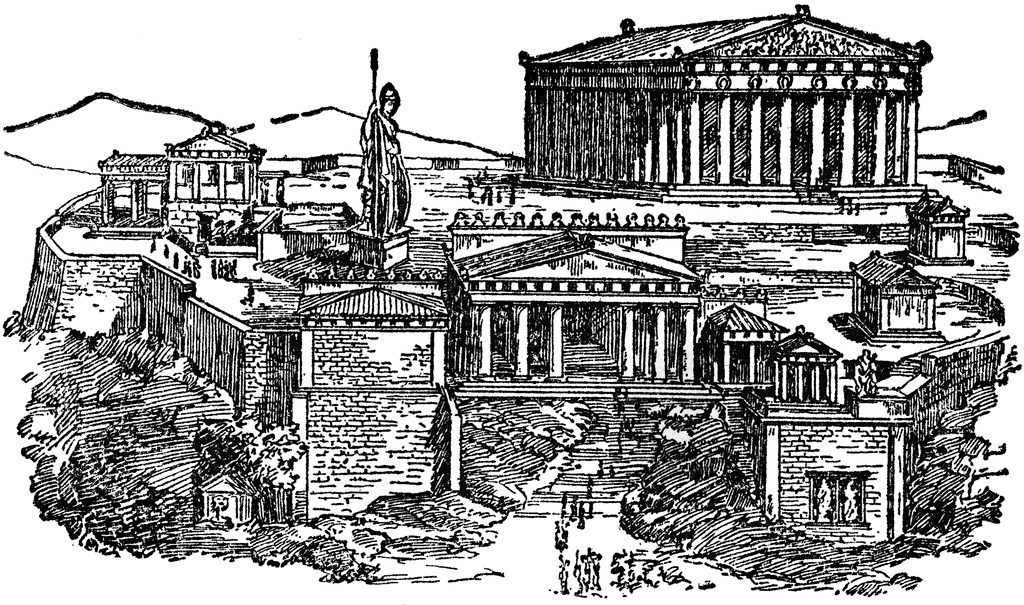

The site of ancient Rhamnous, a Greek city in Attica, overlooking the Euboean Strait, close to Marathon Antiphons birthplace

Speeches

Translated by K. J. Maidment, Loeb Classical Library, 1940

CONTENTS

The Ecclesia in Athens convened on a hill called the Pnyx many of Antiphons speeches were delivered at the Ecclesia of ancient Athens.

Plaster cast bust of the historian Thucydides (in the Pushkin Museum) from a Roman copy (located at Holkham Hall) of an early fourth-century BC Greek original. Thucydides was a great admirer of Antiphon.

Speech I. Prosecution of the Stepmother for Poisoning

Introduction to Prosecution of the Stepmother for Poisoning

T HE FACTS WITH which the Prosecution for Poisoning is concerned may be summarized as follows. A certain Philoneos entertained a friend to dinner at his house in Peiraeus. His mistress served them both with wine after the meal. The wine, it seems, was poisoned; and Philoneos died instantaneously, while his friend fell violently ill and died three weeks later. The woman, who was a slave, was arrested, tortured for information, and executed.

The occasion of the present speech was the reopening of the case some years afterwards by an illegitimate son of the friend. In obedience to his fathers dying command () he charges the fathers wife, his own stepmother, with the murder of her husband and of Philoneos. The stepmothers defence is conducted by her own sons, the prosecutors half-brothers. The line of attack chosen by the prosecution is that the mistress of Philoneos was merely an accessory to the crime: the principal had been the stepmother, who had previously made a similar, but ineffectual, attempt to murder her husband.

It has been suggested that the speech was never intended for actual delivery in a court of law, but that it is simply an academic exercise in the manner of the Tetralogies. The reasons advanced for this are the complete inadequacy of the prosecutions case from a practical point of view, the absence of witnesses, and the seemingly fictitious character of the proper names which occur. However, a brief consideration of the structure and contents will perhaps be enough to show that we have here what is almost certainly a genuine piece of early pleading.

The case for the prosecution rests upon two things: a carefully elaborated narrative of the planning and execution of the murders, and the development of a single argument to the detriment of the defence, the argument that the accused must be guilty, because the defence has refused to allow the family slaves to be questioned under torture about the previous attempt to poison the husband. The refusal, it is assumed, means that the stepmother was guilty of that attempt, and this fact furnishes in its turn a strong presumption, if not proof, of her guilt in the present instance.

This is quite unlike the Tetralogies, where no emphasis is laid on the narrative, the minimum of fact is given, and the writer obviously regards the speeches for the prosecution and defence as an opportunity for demonstrating the possibilities of a priori reasoning and sophistry when a case has to be presented to a jury. It is scarcely credible that the present speech, if composed for the same purpose, should contain so circumstantially detailed a narrative, and at the same time be limited to but a single argument in favour of the prosecution. On the other hand, its peculiar meagreness becomes intelligible if it is assumed that the case was historical but, owing to the circumstances which set it in motion, extremely weak.

Thus, a man lies dying from the effects of the wine which he drank when dining with a friend; the fact that his friend died instantaneously convinces him that they have both been poisoned. He has been on bad terms with his wife for some time, and only recently caught her placing something in his drink. He suspected her at the time of trying to poison him; but she avowed that it was merely a love-philtre. The incident remains in his mind, and the fact that his wife is acquainted with the girl who served his friend and himself with wine at dinner leads him to conclude that she has made a second attempt upon his life, this time with success. He therefore summons his son and solemnly enjoins him to prosecute the wife for murder. The son is bound to carry out the command; but unfortunately there is not a scrap of evidence to show that his stepmother was concerned in his fathers death. The one possible source of information was the supposed accomplice who administered the poison; and no amount of pressure had induced her to say anything to incriminate any second person whatsoever. Hence he has to make what play he can with the imaginary account of the planning of the crime given him by his father. He tries to shift attention to the earlier attempt at poisoning which failed; but the defence refuses to let him question the family slaves about the facts. Thus he is reduced to emphasizing as strongly as possible the damning implications of the refusal. That is why the speech necessarily takes its present unsatisfactory form. On the assumption that the prosecution was set in motion entirely in deference to the fathers , both its unconvincing argumentation and the absence of witnesses become intelligible.

Next page