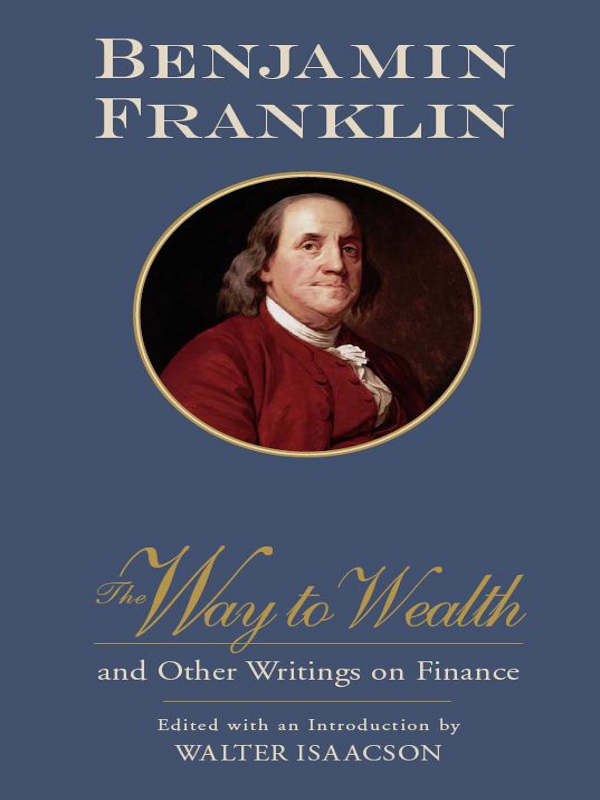

BENJAMIN

FRANKLIN

The Way to Wealth

and Other Writings on Finance

Edited with an Introduction by WALTER ISAACSON

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Published by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016

2006 by The Reference Works, Inc. and

Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Introduction 2006 by Walter Isaacson and The Reference Works, Inc.

Main Events in Franklins Life timeline 2003 by SparkNotes LLC

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or

in part in any form.

Produced by The Reference Works, Inc.

Managing Editor, Pamela Adler

Interior design by Emily Baker

All rights reserved

Sterling ISBN-13: 978-1-4027-3789-3

Sterling eBook ISBN: 978-1-4027-9115-4

For information about custom editions, special sales, premium and

corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales

Department at 800-805-5489 or specialsales@sterlingpub.com.

Table of Contents

by Walter Isaacson

Chapter 2: Working

Chapter 4: Investing

Chapter 6: Protecting

Chapter 8: Paying Taxes

Chapter 10: Bequeathing

Part VI: Poor Richards Way to Wealth

DOING WELL BY

DOING GOOD

by Walter Isaacson

Benjamin Franklins maxims in The Way to Wealth, along with his other writings on personal finance, reflect the many delightful layers of the most modern of all our Founders. He was the original writer of how-to-succeed books. And even though he was not always early to bed or early to rise, he loved giving self-help tips on how we could all become healthy, wealthy, and wise.

But there is an important theme that we must be sure not to miss. Franklins goal was not simply personal wealth. It was alsoas Poor Richard tells usto do well by doing good. In other words, it is possible to become successful by helping others and benefiting the common good. Helping others is part of a virtuous cycle: it makes you more valuable to your community, helps you to serve both your neighbors and your Lord, and also rebounds to your personal credit. To pour forth benefits for the common good was divine, he said. Franklin has always been the founding father who winks at us. George Washingtons colleagues found it hard to imagine touching the austere general on the shoulder, and we would find it even more so today. Jefferson and Adams are just as intimidating. But Ben Franklin, that ambitious urban entrepreneur, seems made of flesh rather than of marble, addressable by nickname, and he turns to us from historys stage with eyes that twinkle from behind those newfangled spectacles. He speaks to us, through his letters and hoaxes and autobiography, not with orotund rhetoric but with a chattiness and clever irony that is very contemporary. We see his reflection in our own time.

Franklin has a particular resonance in twenty-first-century America. A successful publisher and consummate networker with an inventive curiosity, he would have felt right at home in the information revolution. He had unabashed ambition to be part of an upwardly-mobile meritocracy. We can easily imagine having a beer with him after work, showing him how to use a BlackBerry or Treo, and sharing the business plan for a new venture. He would laugh at the latest joke about a priest and a rabbi, or about a farmers daughter. We would admire both his earnestness and his self-aware irony. And we would relate to the way he tried to balance, sometimes uneasily, a pursuit of reputation, wealth, earthly virtues and spiritual values.

His story is a classic one of rags to riches. He ran away from the Puritan town of Boston to the much more tolerant city of brotherly love, Philadelphia. He arrived tired and bedraggled and with but a few coins in his pocket. But he soon found work in a print shop, and eventually he built a printing business of his own. He helped create the content to fuel it, then he franchised his businesses all up and down the colonial coast, and finally he created a postal system to act as his distribution system. It was a way to wealth worthy of any twenty-first-century media baron.

Franklin was a natural shopkeeper: clever, charming, astute about human nature, and eager to succeed. He became, as he put it, an expert at selling. His printing and publishing business succeeded largely due to his charm and diligence. Franklin became an apostle of beingand, just as important, appearing to beindustrious. Even after he became successful, he made a show of personally carting the rolls of paper he bought in a wheelbarrow down the street to his shop, rather than having a hired hand do it.

He was also the consummate networker. He liked to mix his civic life with his social one, and he merrily leveraged both to further his business life. This approach was evident when he formed a club of young workingmen, in the fall of 1727 shortly after his return to Philadelphia, that was commonly called The Leather Apron Club and officially dubbed The Junto.

Franklins little club was composed of enterprising tradesmen and artisans, rather than the social elite who had their own fancier gentlemens clubs. At first the members went to a local tavern for their Friday evening meetings, but soon they were able to rent a house of their own. There they discussed issues of the day, debated philosophical topics, devised schemes for self-improvement, and formed a network for the furtherance of their own careers.

The enterprise was typical of Franklin, who seemed ever eager to organize clubs and associations for mutual benefit, and it was also typically American. As the nation developed a shopkeeping middle class, its people balanced their individualist streaks with a propensity to form clubs, lodges, associations, and fraternal orders. Franklin epitomized this Rotarian urge and has remained, after more than two centuries, a symbol of it.

In his club of aspiring shopkeepers and artisans, Franklin laid out a guide for the type of conversational contributions each member could usefully make. The questions he chose were a model of mixed practicality, good works, and tips for success:

What new story have you lately heard agreeable for telling in conversation? Hath any citizen in your knowledge failed in his business lately, and what have you heard of the cause? Have you lately heard of any citizens thriving well, and by what means? Have you lately heard how any present rich man, here or elsewhere, got his estate? Do you know of any fellow citizen who has lately done a worthy action deserving praise and imitation? Is there any man whose friendship you want and which the Junto or any of them can procure for you?... In what manner can the Junto or any of them assist you in any of your honorable designs?

Franklins historical reputation has been largely shaped, for disciples and detractors alike, by his account in his autobiography of the famous project he launched to attain moral perfection. This rather odd endeavor, which involved sequentially practicing a list of virtues, seems at once so earnest and mechanical that one cannot help either admiring him or ridiculing him. As the novelist D. H. Lawrence later sneered: He made himself a list of virtues, which he trotted inside like a gray nag in a paddock.

So its important to note the hints of irony and self-deprecation in his droll recollection, written when he was 79, of what he wryly dubbed the bold and arduous project of arriving at moral perfection. First, he made a list of twelve virtues he thought desirable, and to each he appended a short, and often revealing, definition:

Next page