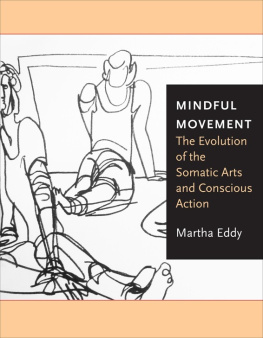

The Martha Graham Dance Company

The Martha Graham Dance Company

House of the Pelvic Truth

Blakeley White-McGuire

Any great art is the condensation of a strong emotion: a perfectly conscious thing.

Martha Graham (1927)

This book was researched and written during the pandemic of 20201 on the unceded ancestral land of the Leni Lanape people, also known as the island of Manhattan, New York City.

To my family in blood and spirit for believing that everything is possible; for holding the space for me to stand tall.

I dance my gratitude and thanksgiving to you.

To my fellow dancers of all forms and expressions. Our sacred experiences of the bodys mystery, majesty, and power binds us together through time and generations.

And

I would like to acknowledge Dana Mills for her unwavering confidence in me.

This book would not have been written without your interventions.

Thank you, Dana.

There were few opportunities to study modern dance techniques in South Louisiana, United States of America where I was born and raised. Luckily, a presenting partnership between the regional Baton Rouge Ballet Theater and Louisiana State Universitys Dance Department provided me a life-changing opportunity to see the Martha Graham Ensemble perform live in my native home. The repertory consisted of three classic Graham choreographies El Penetinte, Helios from Acts of Light, and Diversion of Angels. I also took my first Graham master class that day with dancer Sandra Kaufmann. After that I became deeply curious about Martha Graham, the dancer/artist. The sophistication of and symbolism in her work inspired me to move. Soon after I was on my way to New York, to a new life. I was eighteen years old.

I consider it a gift and a privilege to have had access to the dances, technique, and personal lineage that is embodied through the Martha Graham Dance Company. During my career with the Company (200116, 2017) and before that with the Martha Graham Ensemble (19956), I danced as chorus, soloist and principal dancer interpreting the roles which Graham created for herself. That body of work facilitated the development of my stage presence as well as my emotional capacity to execute the literature of Grahams repertory. I earned a wealth of knowledge about communicating in the sacred language of human movement. Grahams canon provided agency for me to feel my female dancing body as powerful and beautiful, as a subject for discovery rather than an object. Her movements came not only from herself but also from those dancers who worked with her and who gave significant time in their own lives to help her develop the technique and repertory. Thanks to this community of lineage, the Graham technique of modern dance is available for all bodies to access. Grahams canon is in the DNA of contemporary concert dance; her work has had a generational impact on many contemporary dance companies around the world including Batsheva in Israel, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Paul Taylors American Modern Dance and Buglisi Dance Theater in New York, Cloud Gate in Taiwan, and London Contemporary Dance in the United Kingdom.

Indeed, it is impossible to separate the two. Whenever I dance a Graham work, teach or take a Graham class, I am performing a sacred action in my life.

The second company which at that time performed in New York dance seasons and international touring under Director Kazuko Hirabayashi.

Graham, Blood Memory.

I did not choose to become a dancer, I was chosen and with that you live all of your life.

Martha Graham

Modern dancer and choreographer Martha Graham (18941991) devoted her life to the practical work of creating art with the dancing body. She was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania and died in New York City, NY. Her father was a doctor of nervous disorders, a psychiatrist. Her mother held the traditional Western role for a woman, bearing four children; three girls (Martha was the eldest) and a boy who died in early childhood. In her autobiography, Blood Memory (Doubleday Publishing, 1991) Graham recounts her experiences of a childhood full of history, a love for animals and a closeness with her father in particular. As a girl, she moved with her family across North America from Pennsylvania in the East to Santa Barbara, California in the West. This adventure made a great impact upon what would later become her artistic aesthetics including her use of imagistic expansive space and a direct horizontal gaze in her dances.

Her first dance training began around 1916 when she enrolled at The Denishawn School of Dance and Related Arts founded by Ruth St. Denis and her husband Ted Shawn in Los Angeles, California. There she would begin her life as an artist. She eventually returned East to New York City where she found work dancing in the Greenwich Village Follies. In forming her company she laid a foundation that would make her one of the most celebrated creative minds of the twentieth century. In the early to mid-twentieth century, modern dance developed from a personal practice of discovery into a performing art genre. It formed primarily (but not exclusively) in New York City through a unique societal interplay of The Great Depression, immigration, activism in civil rights; including womens suffrage, and the development of psychology. Graham saw desperate people standing on breadlines and used those images in her early dances such as Chronicle (1936). Many of her early dancers were the children of Jewish immigrants and refugees fleeing persecution and war. In a time when the United States was at war with Japan, and the inhuman practice of apartheid was still enforced in parts of the United States, Graham created a company that employed dancers based on content of their work not on the color of their skin. She lived as an independent woman, married for a time to choreographer Erik Hawkins, but she remained childless in a time when women still held very traditional roles in US society. Artists search for new definitions behind accepted symbols; she was an artist interrogating our human experience during the modern era.

Choreographers at that time mined the body for information; many developed physical vocabularies and aesthetics through collaborative experimentations. In its nascency, the genre manifested through individual artists such as Graham, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman, Katherine Dunham, Pearl Primus, Michio Ito, Lester Horton, Mary Wigman, and many others who were devoted to developing codified techniques and dances for repertory performance groups. Themes of humanism, spiritual endurance, mysticism, political unrest, and the power of masses to transgress societal norms dominated early works. Through the dance practice of transmitting lineal knowledge in the master/apprentice model, many of the dances and practices of the period are still accessible. At this writing, thirty years after her death, Grahams voice in particular still resonates vibrantly through an artistic canon of repertory, codified dance technique and philosophies for living as a dancer in the modern world. Her dances celebrate the vitality of human emotion using movement as medium. Through its breadth and scope, Grahams canon empowers its practitioners to embrace their physical power and artistic expressions, sometimes in the face of oppressive societal norms.

A dancing body functions in discourse with personal stories, desires, and latent potential. Dancing reveals aspects of a person where words fall short. To dance is a primary human inheritance; the role of the dancer is to bring this wealth to mind. As Graham said countless times in in varying contexts throughout her life movement never lies. She shared the genesis of this affirmation in her autobiography,

Next page