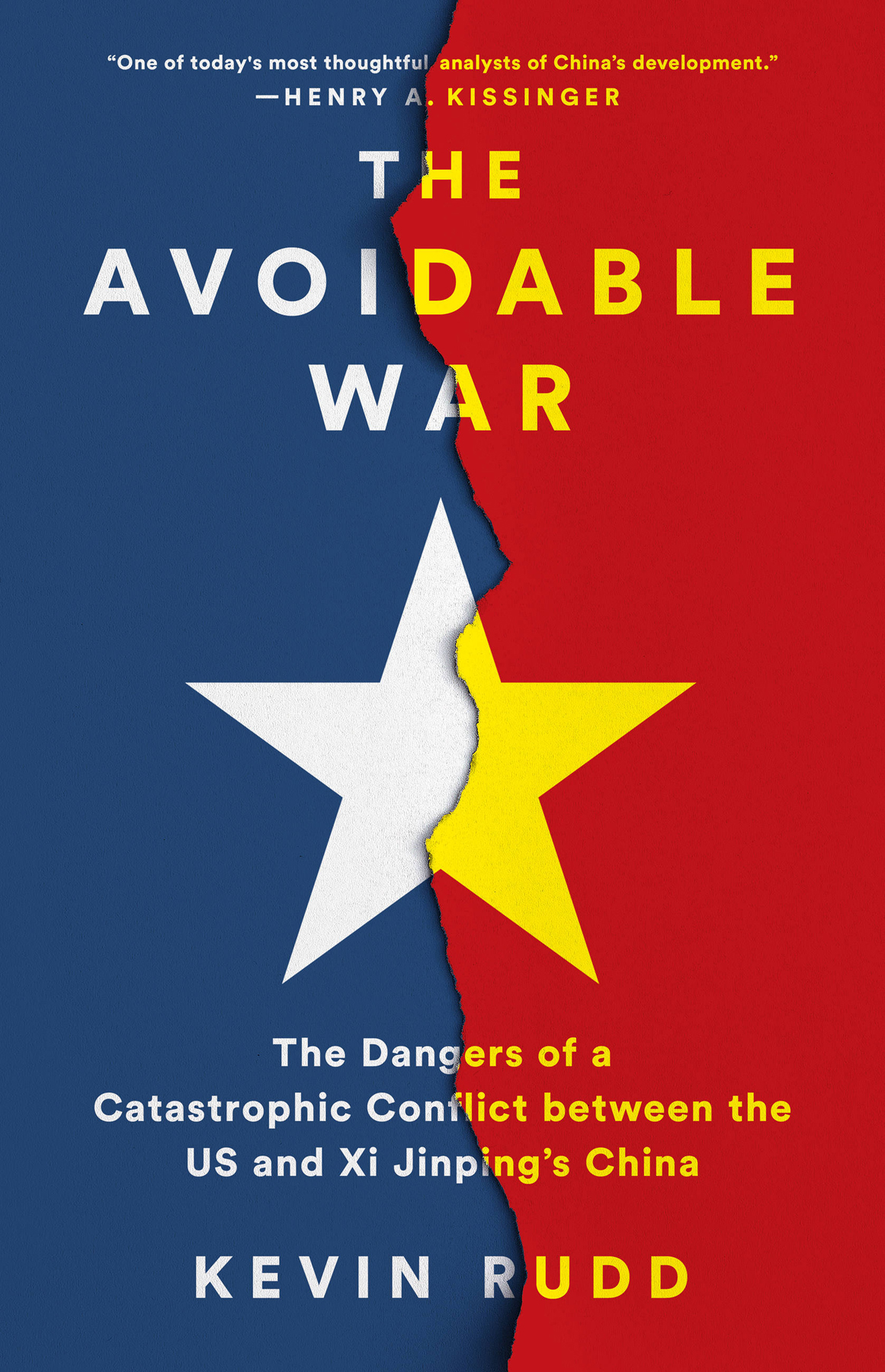

Copyright 2022 by Kevin Rudd

Cover design by Pete Garceau

Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

PublicAffairs

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.publicaffairsbooks.com

@Public_Affairs

First Edition: March 2022

Published by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The PublicAffairs name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021952259

ISBNs: 9781541701298 (hardcover), 9781541701304 (e-book)

E3-20220202-JV-NF-ORI

Dedicated to our three little grandkids, Josephine, Mackie, and Scarlett, and to precious grandchildren the world over as our generation contemplates decisions that will determine whether these little ones get to live in poverty, fear, and waror prosperity, freedom, and peace.

I wish I did not have to write this book. I am just old enough to remember marching as a small child in our annual ANZAC Day paradethe Australian equivalent of Memorial Dayin our tiny country town with my father, who had fought in World War II. I also remember marching beside men in their seventies, by then a little unsteady on their feet, who had fought back in World War I. One of them, my father confided in me, still suffered from shell shock.

There was nothing inevitable about the Great War from 1914 to 1918. It came about because of the flawed decisions of political and military leaders in July and August 1914. Thats what led to the slaughter. Those decisions cost approximately 40 million lives, including 117,000 Americans and 60,000 Australians. The decisions about how to punish the losers of that war set the fuse for the next global conflagration, one so horrific that when it was done, as many as 85 millionapproximately 3 percent of the worlds populationlay dead.

When I think of the collective killings of the last century, I fully acknowledge that my mindset forces me to make every effort to do whatever can be done to avoid yet another episode of global carnage on an industrial scale. In doing so, however, we must not only maintain the peace but also preserve the national and individual freedoms that our forebears fought to secure over the many centuries that have passed since the Enlightenment. We must be ever mindful of the debacle of Neville Chamberlains proclamation, having handed the Sudetenland to Hitler in Munich in 1938, that hed come home to London bringing peace with honor and urged the people of Britain to go home and sleep quietly in your beds. The uncomfortable truth is there can never be peace at any price.

This brings us to the unfolding crisis in the relationship between China and the United States. The 2020s loom as a decisive decade in the overall dynamics of the changing balance of power between them. Both Chinese and American strategists know this. For policy makers in Beijing and Washington, as well as in other capitals, the 2020s will be the decade of living dangerously. Beneath the surface, the stakes have never been higher or the contest sharper, whatever diplomats and politicians may say publicly. Should these two giants find a way to coexist without betraying their core intereststhrough what I call managed strategic competitionthe world will be better for it. Should they fail, down the other path lies the possibility of a war that could rewrite the future of both countries and the world in a way we can barely imagine.

A Student of China and America

I have been a student of China since I was eighteen years old, beginning with my undergraduate degree at the Australian National University, where I majored in Mandarin Chinese and classical and modern Chinese history. I have lived and worked in Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Taipei through different diplomatic postings and have developed many, many friendships right across greater China. I have traveled back to China and Taiwan on innumerable occasions over the last forty years, including in my role as prime minister of Australia, personally meeting with Xi Jinping and other senior Chinese leaders many times. I admire Chinas classical civilization, including its remarkable philosophical, literary, and artistic traditions, as well as the economic achievements of the post-Mao era in lifting a quarter of humanity out of poverty.

At the same time, I have been deeply critical of Maos depredations of the country during the Great Leap Forward of 1958, which left some thirty million dead from starvation; the Cultural Revolution, in which Mao eliminated his political enemies through Stalinesque show trials, leading to millions of deaths and the destruction of priceless cultural heritage at the same time; and human rights abuses that continue to this day. My undergraduate dissertation at the Australian National University, Human Rights in ChinaThe Case of Wei Jingsheng, forced me to retrace the sad and sorry history of the concept of rights throughout both the classical and the Communist periods. I had simply read too muchand seen too muchover the years to politely brush it all under the carpet. I am still haunted by the thousands of young faces in Tiananmen Square in late May 1989, when I spent the better part of a week walking and talking among thembefore the tanks moved in on June 4. Thats why I could not avoid the whole question of human rights when, nearly twenty years later, I returned to Beijing as Australias prime minister on my inaugural visit. I traveled to Peking University to deliver a public lecture in Chinese on the very first day of my visit, where I argued that the best classical traditions of friendship within the Chinese tradition (the concept of zhengyou ) meant that friends could candidly speak to each other without rupturing the relationship. Within that frame, I raised human rights abuses in Tibet in the middle of my speech. The Chinese foreign ministry went nuts. So, too, did the more supine members of the Australian political class, business community, and media, who did what they always do: they asked, How could you upset our Chinese hosts by mentioning the unmentionable? The answer was reasonably straightforward: because it happened to be the truth, and to ignore it was to ignore part of the complex reality of any countrys relationship with the Peoples Republic.

I have also lived for a number of years in the United States. I have a deep affection for Americans, a profound interest in American history, and a deep admiration for the countrys extraordinary culture of innovation. I am intimately aware of the differences between the two countries, but Ive also seen the great cultural values they have in commonthe love of family, the importance that both Chinese and Americans attach to the education of their children, and their vibrant entrepreneurial cultures driven by aspiration and hard work. No approach to understanding US-China relations is free from intellectual and cultural prejudice. For all my education in Chinese history and thought, I am inescapably and unapologetically a creature of the West. I therefore belong to its philosophical, religious, and cultural traditions. The country I served as both prime minister and foreign minister has been an ally of the United States for more than one hundred years and actively supports the continuation of the liberal international order built by the United States out of the ashes of World War II. At the same time, I have never accepted the view that an alliance with the United States mandates automatic compliance with every element of American foreign and security policy. This has been demonstrated by the fact that despite pressure from Washington, my political party, the Australian Labor Party, opposed both the Vietnam War and the invasion of Iraq. Nor do I have a rose-colored view of American domestic politics and its endemic problems of uncontrolled campaign finance, the corruption of the redistricting system, and the politics of voter suppression. Nor am I complacent about the unsustainable economic inequalities that we find increasing across American society and that have fueled a new wave of populist extremism.