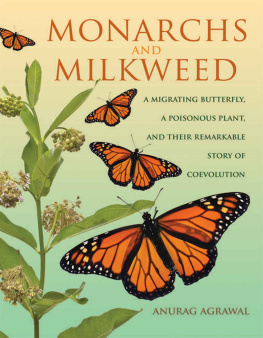

Monarchs and Milkweed

Monarchs and Milkweed

A MIGRATING BUTTERFLY, A POISONOUS PLANT, AND THEIR REMARKABLE STORY OF COEVOLUTION

Anurag Agrawal

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2017 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket photos by Ellen Woods

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Agrawal, Anurag A.

Title: Monarchs and milkweed : a migrating butterfly, a poisonous plant, and their remarkable story of coevolution / Anurag Agrawal.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016034053 | ISBN 9780691166353 (hardback : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Monarch butterfly. | Milkweed butterflies. | Milkweeds. | Coevolution.

Classification: LCC QL561.D3 A47 2017 | DDC 595.78/9dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016034053

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book was supported in part by Cornell Universitys Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future (www.acsf.cornell.edu)

This book has been composed in Perpetua Std

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in China

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Monarchs and Milkweed

CHAPTER 1

Welcome to the Monarchy

You who go through the day

like a wingd tiger

burning as you fly

tell me what supernatural life

is painted on your wings

so that after this life

I may see you in my night

Homero Aridjis, To a Monarch Butterfly

The monarch butterfly is a handsome and heroic migrator. It is a flamboyant transformer: an egg hatches into a white, yellow, and black-striped caterpillar; then a metamorphosis takes place inside its leafy-green chrysalis, which is endowed with gold spots; the adult butterfly that emerges flaunts orange and black (). In the monarchs annual migratory cycleperhaps the most widely appreciated fact about themindividual butterflies travel up to five thousand kilometers (three thousand miles), from the United States and Canada to overwintering grounds in the highlands of Mexico. After four months of rest, the same butterflies migrate back to the United States in the spring. Come summer, their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren will populate the northern regions of America.

But there is much more to the monarchs story than bright coloration and a penchant for epic journeys. For millions of years, monarchs have engaged in an evolutionary battle. The monarchs foe in this struggle is the milkweed plant, which takes its name from the sticky white emissions that exude from its leaves when they are damaged. The monarch-milkweed confrontation takes place on these leaves, which monarch caterpillars consume voraciously, as the plant is their exclusive food source. Milkweeds, in turn, have evolved increasingly elaborate and diversified defenses in response to herbivory. The plants produce toxic chemicals, bristly leaves, and gummy latex to defend themselves against being eaten. In what may be considered a coevolutionary arms race, biological enemies such as monarchs and milkweeds have escalated their tactics over the eons. The monarch exploits, and the milkweed defends. Such reciprocal evolution has been likened to the arms races of political entities that stockpile more and increasingly lethal weapons.

FIGURE 1.1. The monarch butterfly in three stages: (a) a caterpillar eating a milkweed leaf, (b) a chrysalis undergoing metamorphosis, and (c) an emerging butterfly before it expands its wings.

This book tells the story of monarchs and milkweeds. Our journey parallels that of the monarchs biological life cycle, which starts each spring with a flight from Mexico to the United States. As we follow monarchs from eggs to caterpillars, we will see how and why they evolved a dependency on milkweed and what milkweed has done to fight back (). We will discover the potency of a toxic plant and how a butterfly evolved to overcome and embrace this toxicity. As monarchs transition to adulthood at the end of the summer, their dependency on milkweed ceases, and they begin their southward journey. We will follow their migration, which eventually leads them to a remote overwintering site, hidden in the high mountains of central Mexico. Along the way, we will detour into the heart-stopping chemistry of milkweeds, the community of other insects that feed on milkweed, and the conservation efforts to protect monarchs and the environments they traverse.

To be sure, this story is about much more than monarchs and milkweeds; these creatures serve as royal representatives of all interacting species, revealing some of the most important issues in biology. As we will see, they have helped to advance our knowledge of seemingly far-flung topics, from navigation by the sun to cancer therapies. We will also meet the scientists, including myself, who study the mysteries of long-distance migration, toxic chemicals, the inner workings of animal guts, and, of course, coevolutionary arms races. We will witness the thrill of collaboration and competition among scientists seeking to understand these beautiful organisms and to conserve the species and the ecosystems they inhabit.

FIGURE 1.2. An unlucky monarch butterfly caterpillar that died after taking its first few bites of milkweed, the only plant it is capable of eating. In a violent and effective defense, toxic and sticky latex was exuded and drowned the caterpillar. A substantial fraction of all young monarchs die this way.

FROM SIMPLE BEGINNINGS

From a single common ancestor, milkweeds diversified in North America to more than one hundred species. And the monarch lineage is no slouch, with hundreds of relatives we call milkweed butterflies throughout the world. Although monarchs are perhaps best known in the northeastern and midwestern United States, they occur throughout North America, and self-sustaining populations have been introduced to Hawaii, Spain, Australia, New Zealand, and elsewhere (). Interactions between butterflies and milkweeds now occur throughout the world, but this account focuses primarily on what happens in North America. The reason is quite simple: eastern North America is where the monarch (

Next page