Copyright 2020 Joseph Wang

All rights reserved.

ISBN 978-0-9991367-4-4

New York, 2020

Contents

Preface

I dreamed of working in the financial markets. Unfortunately, I did not have that dream until after I graduated from Columbia Law School on the eve of the great financial crisis. While I sat in my office re-reading a 200-page loan agreement for the fourth time, I was aware that the world around me was changing. The Dow was gyrating a few percentage points a day, major financial institutions were teetering on collapse, and the Fed was printing money in a way it had never done before. I didnt understand much of what was going on, but it was exciting. I wanted to understand how it all worked.

I applied to over a hundred jobs in the financial markets, but the post-crisis world was not the best time to join the finance industry. Every job posting was flooded with resumes from newly laid-off bankers and traders (and a fair number of lawyers desperate to escape their tedious careers). Ultimately, I made my transition into the financial services by going back to school for a masters in economics at Oxford University. I had fortunately studied math and economics in college, so the shift was manageable. After a stint as a credit analyst, I landed a role as a trader on the Open Markets Desk of the New York Fed.

My time on the Desk offered me a glimpse behind the curtain as to how the financial system really worked. This is because the Desk has two very important responsibilities: gathering market intelligence for policy makers and executing open market operations.

Gathering market intelligence means having candid conversations with market participants on how they are viewing the market. The Desk regularly speaks with virtually every major market participant, from prominent investment banks to Fortune 500 corporate treasurers to large hedge funds. In addition, the Desk itself has access to extensive volumes of confidential data the Fed collects through its regulatory powers. The qualitative discussions and hard data give the Desk a substantial edge in understanding financial markets.

Executing open market operations means implementing the monetary policies decided by the Federal Open Markets Committee, such as large-scale asset purchases and FX-swap operations. The financial panics in 2008 and 2020 that swept through global markets were only stabilized when the Desk stepped up its operations. Open market operations basically mean printing money, sometimes a lot of money.

I took full advantage of my time on the Desk to learn as much as I could about the monetary system and the broader financial system. I often noticed that many people, even seasoned professionals, did not have a very strong understanding of how the monetary system worked. For example, the Feds first foray into quantitative easing in 2008 sent the professional investment community into a frenzy. Gold prices skyrocketed to all-time highs as investors anticipated imminent hyperinflation, but not even mild inflation materialized.

The misunderstanding is understandable, as central banking is very complicated. There is a lot of conflicting information, even from purported experts. Without my time on the Desk, I would still be very fuzzy on many aspects of how the monetary system works. I remember sitting in my law office being intensely interested in understanding quantitative easing and what the Fed was doing, but forced to piece things together based on articles and blog posts by people that appeared to be credible. I couldnt find better resources.

Central Banking 101 is aimed at teaching the foundational aspects of central banking, as well as offering an overview of the financial markets. While intended as a broad introduction, it also includes special highlighted sections that offer deeper insight for more knowledgeable readers. Central Banking 101 is the book that I wish I had been able to read when I first began my journey in understanding the monetary system and the broader financial system.

I hope you find it interesting and helpful.

Note, the views I express are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System.

Section I Money and Banking

Chapter 1 Types of Money

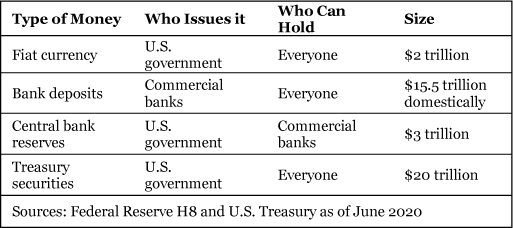

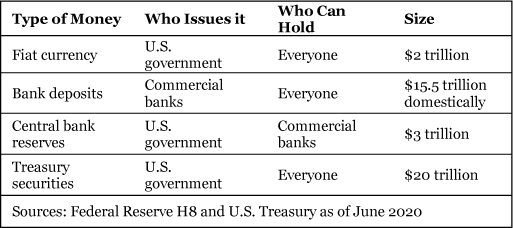

What is money? When most people think of money, they picture rectangular pieces of government-printed paper, known as fiat currency, decorated with historical figures. Although this is the most well-known form of money, it is only a small part of what constitutes money in the modern financial system. Look in your wallet and think about your dayhow much currency do you carry and use? If you are like most people, then your salary is wired into your bank account and spent via electronic payments. The numbers that you see in a bank account are called bank deposits, a separate type of money that is created by commercial banks, not the government. Bank deposits are the vast majority of what the public thinks of as money.

In practice, bank deposits can be seamlessly converted into government-issued fiat currencies in real time at any bank or ATM machine. But the two are very different. A bank deposit is an IOU from a bank that can become worthless if the issuing bank goes bankrupt. On the other hand, a $100 dollar bill is issued by the Federal Reserve, which is part of the U.S. government. That $100 bill will have value as long as the United States exists. There is much more money in bank deposits than there is in paper bills, so in theory, a bank would run out of cash if everyone withdrew their deposits. But thats not really an issue because people today feel safe holding bank deposits, in part because the government provides $250,000 in FDIC deposit insurance for account holders. This makes bank deposits as safe as fiat currency for most people.

The third type of money is central bank reserves, a special type of money issued by the Federal Reserve that only commercial banks can hold. Much like a customers bank deposit is an IOU from a commercial bank, a central bank reserve is an IOU from the Federal Reserve. From a commercial banks standpoint, currency and bank reserves are interchangeable. A commercial bank can convert its bank reserves to fiat currency by calling up the Federal Reserve and asking for a shipment of currency. A $1000 shipment of currency would be paid for by a $1000 decline in reserves from its account at the Fed. Commercial banks use bank reserves when they pay each other or anyone else who also has a Fed account, and they use currency or bank deposits to pay everyone else.

The final type of money is Treasuries, which is basically a type of money that also pays interest. Just like fiat currencies and central bank reserves, Treasuries are issued by the U.S. government. They can be readily convertible to bank deposits by selling them in the market or by using them as collateral for a loan. Imagine that you are a large institutional investor or very wealthy person with hundreds of millions of dollars. You are not eligible to hold central bank reserves because you are not a bank, it would not make sense for you to deposit all that money at a commercial bank because it far exceeds FDIC insurance limits, and it would be silly to hold a mountain of fiat currency at home. For you, Treasuries are money.

In a functional financial system, all forms of money are freely convertible to each other. When that conversion breaks down, then serious problems in the financial system emerge. In the following sections, we will discuss each type of money and provide illustrations of what happens when their convertibility is impaired.