Page List

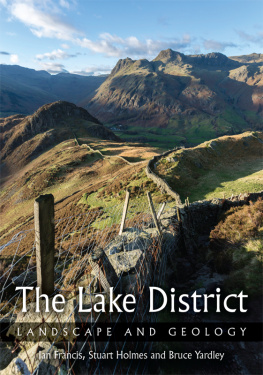

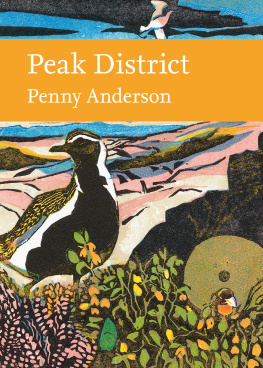

The Peak District

LANDSCAPE AND GEOLOGY

Ladybower Reservoir and the Dark Peak, seen from Bamford Edge.

The Peak District

LANDSCAPE AND GEOLOGY

Tony Waltham

First published in 2021 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

Tony Waltham 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 875 7

Acknowledgements

Maps in these pages have been abstracted and compiled from numerous sources, before being redrawn and embellished by the author. Due credit belongs to members of the British Geological Survey for their source information and mapping, and also to the many cavers who made the original underground surveys.

A huge thank you and great credit go to the late Paul Deakin, mine surveyor, caver and photographer who lived in the Peak District and left a massive legacy of excellent photographs of mines and caves all over Britain; Pauls images are on pages ). All other photographs are by the author.

Thank you also to Dave Lowe, Peter Worsley, Noel Worley and Don Cameron who reviewed draft texts of some chapters; to Judy Rigby for providing fossils from her collection; and to the late Trevor Ford, whose knowledge of the Peak District was both massive and infectious.

The book is dedicated to the authors wife Jan, whose boundless support made everything possible, and who appears as scale in many of the photographs.

Front cover: Reef limestone forming the great white cliff of High Tor, seen from Masson Hill across the Derwent Gorge, with Riber Castle on the grit escarpment beyond.

Cover design by Maggie Mellett

CHAPTER 1

White Peak and Dark Peak

Limestone gorges, swathes of green pasture, villages of stone, grit edges and peat moors: these are the features that distinguish the Peak District. Each could claim to be iconic, but it is the combination of them all that makes the real splendour and the glorious landscapes of this southern section of the Pennine Hills.

The hills at Castleton are a microcosm of Peak District landscapes.

The limestone of Treak Cliff is in the foreground with the Winnats gorge cut in behind it, all parts of the White Peak.

Within the Dark Peak, Mam Tor and its landslide are just beyond, then Edale lies in front of the grit moors of Kinder Scout that stand high in the distance.

Even within the national park, there are two very distinct halves to the Peak District, each with its own style of landscape. On the outcrop of the limestone, the White Peak forms most of the southern half of the park. It is a land of farming, with some fields of crops but many more of fescue grass pasture for grazing sheep, to such an extent that in summer it should perhaps be called the Green Peak. In contrast, the Dark Peak is on the gritstone country that forms the smaller northern half of the park and also extends into southern arms on each side of the White Peak. It is a land with little farming value, relished only by the grouse that nest in the heather. With peat bogs and the dark Juncus reed grasses, it looks more like a Brown Peak except during the seasonal bloom of purple heather.

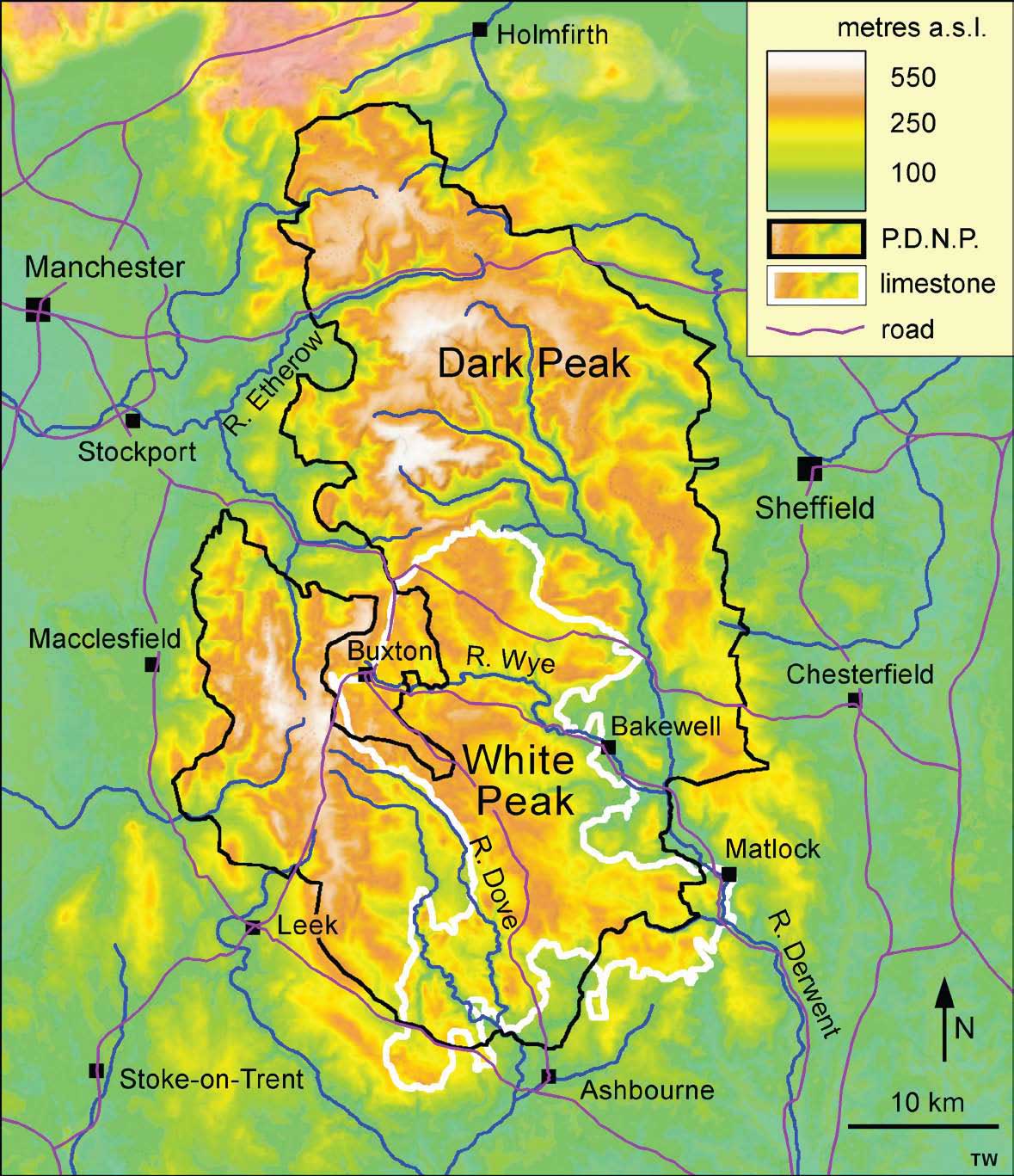

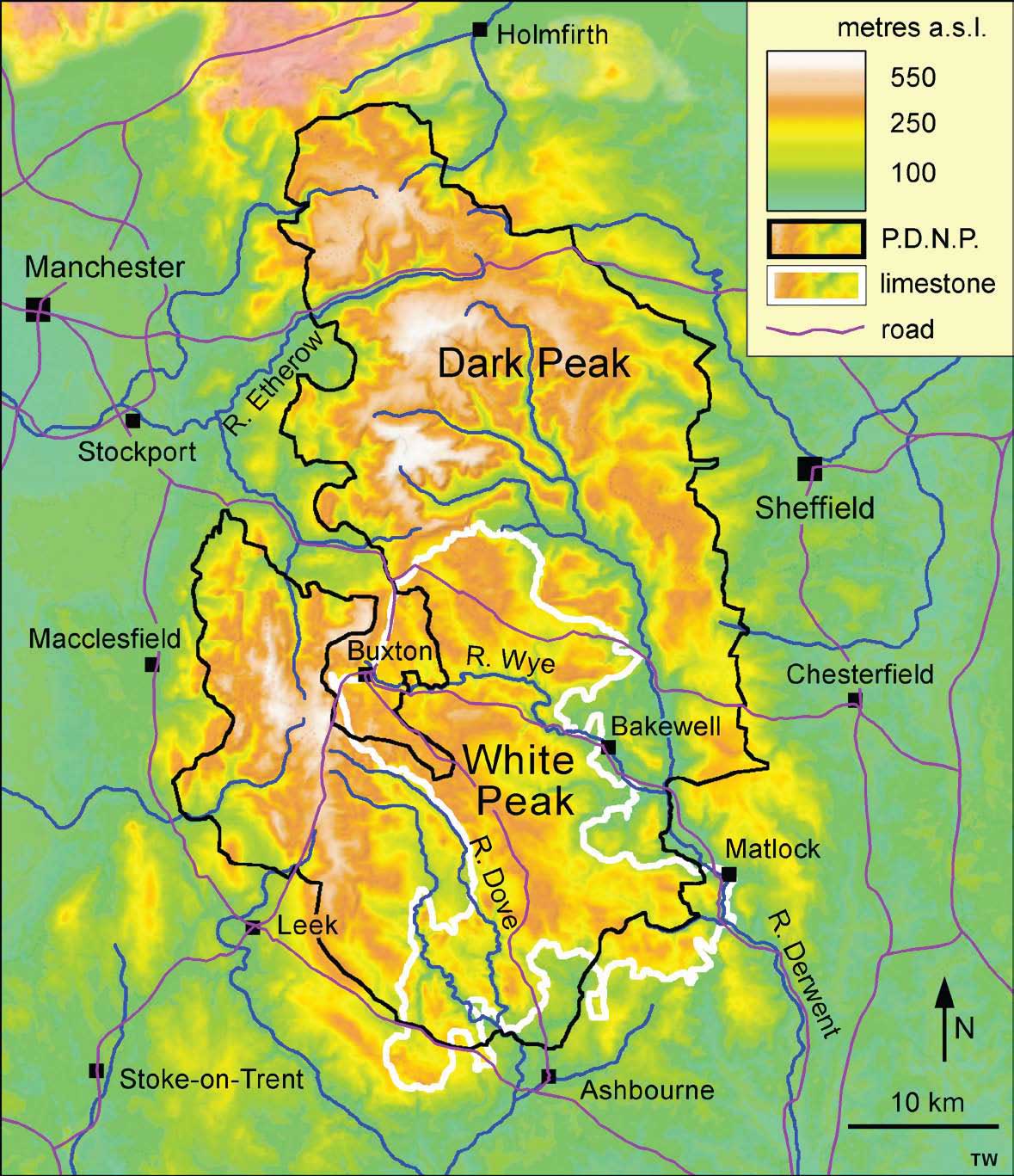

The high ground of the Pennines and the Peak District, between their adjacent lowlands, with the boundary of the Peak District National Park and the margin of the limestone outcrop that defines the White Peak.

These two landscapes, each on its own rock type, have both been carved out by a million or more years of erosion, and that has been largely by rainwater, streams and rivers. Ice Age glaciers did leave their mark across the Peak District, but mainly in rather subtle ways, and practically all the landforms, whether of White Peak limestone or Dark Peak gritstone, were fashioned by water erosion.

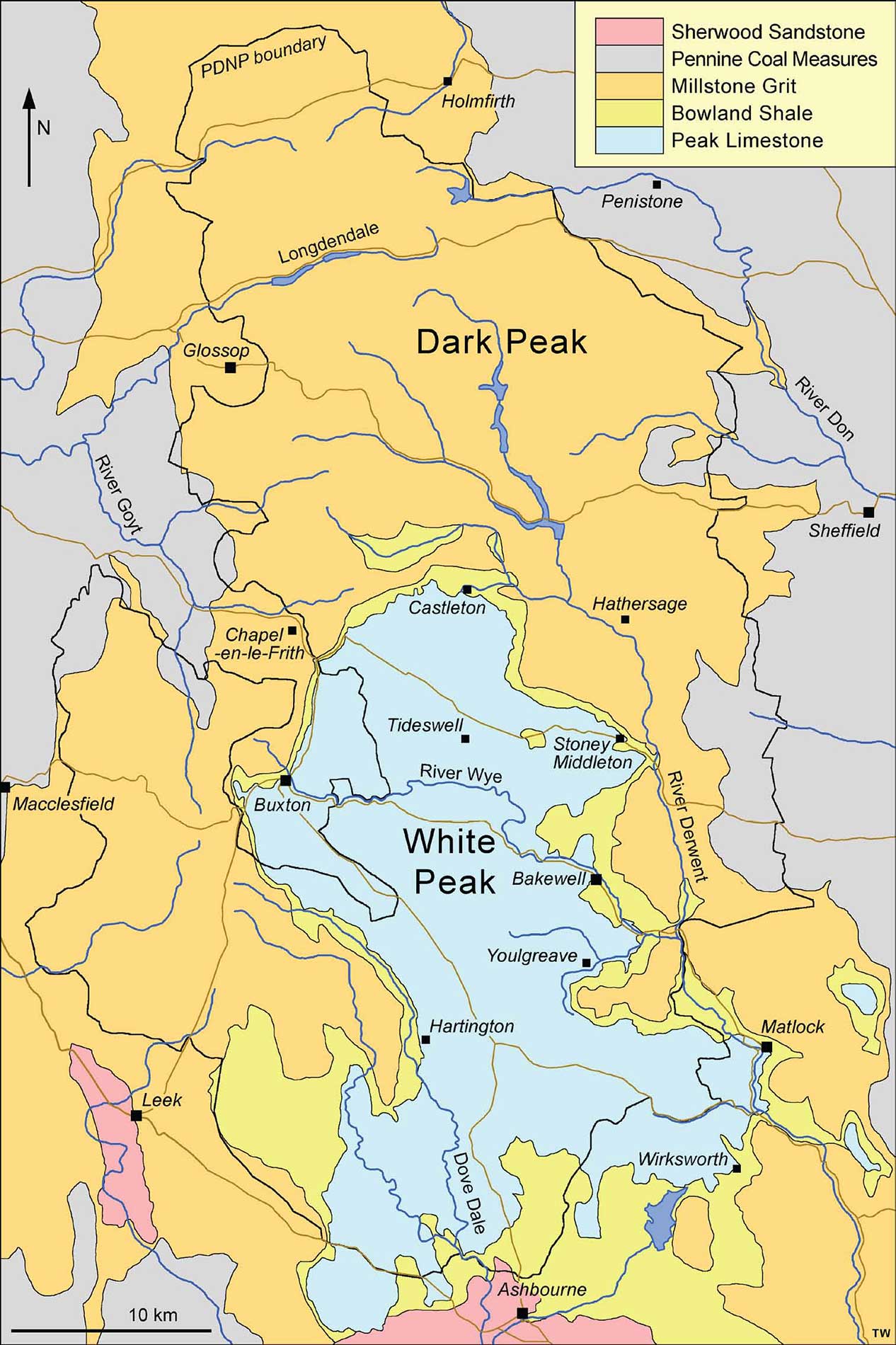

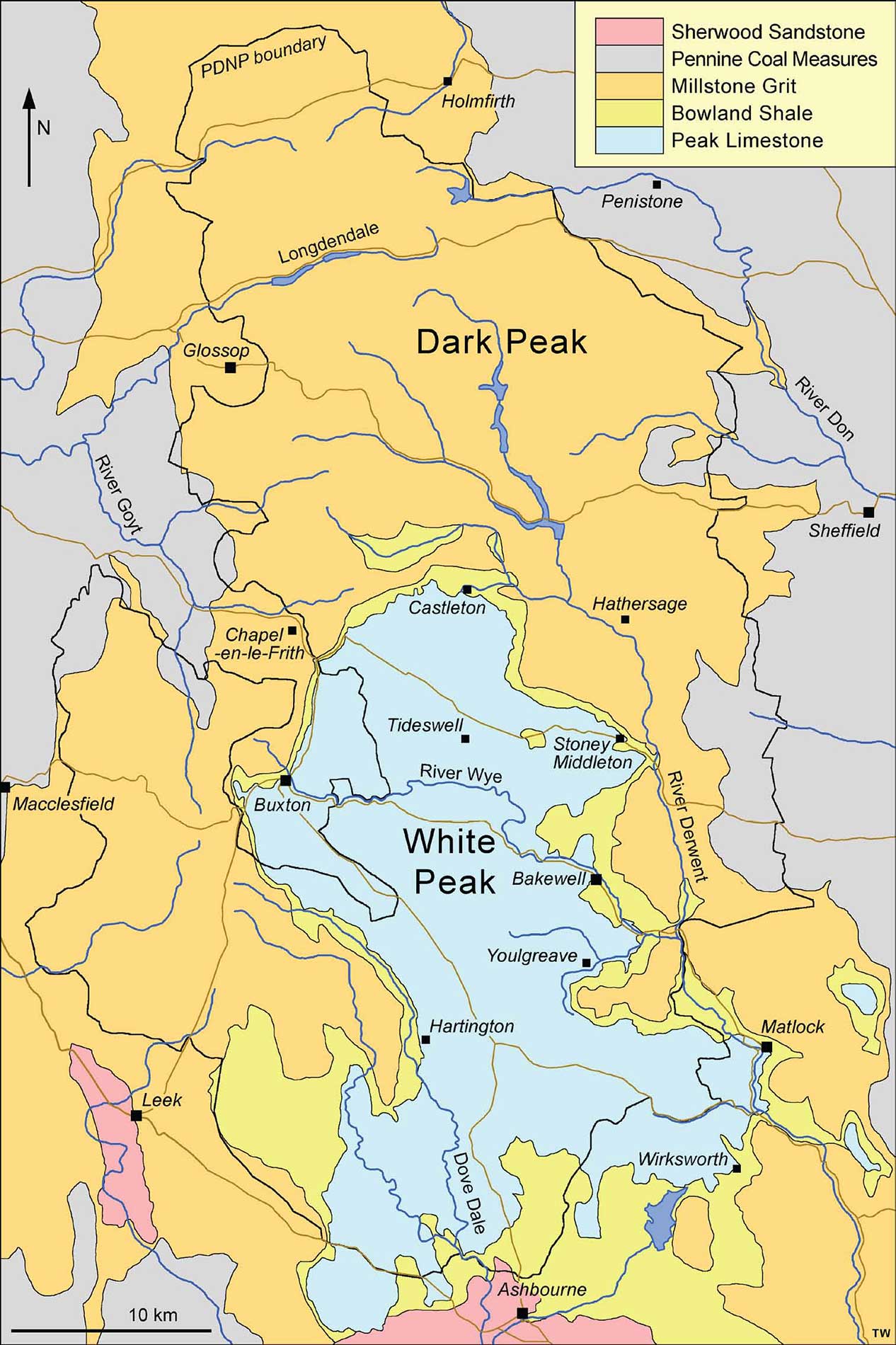

Outline geology of the Peak District, with the National Park boundary shown in black.

.

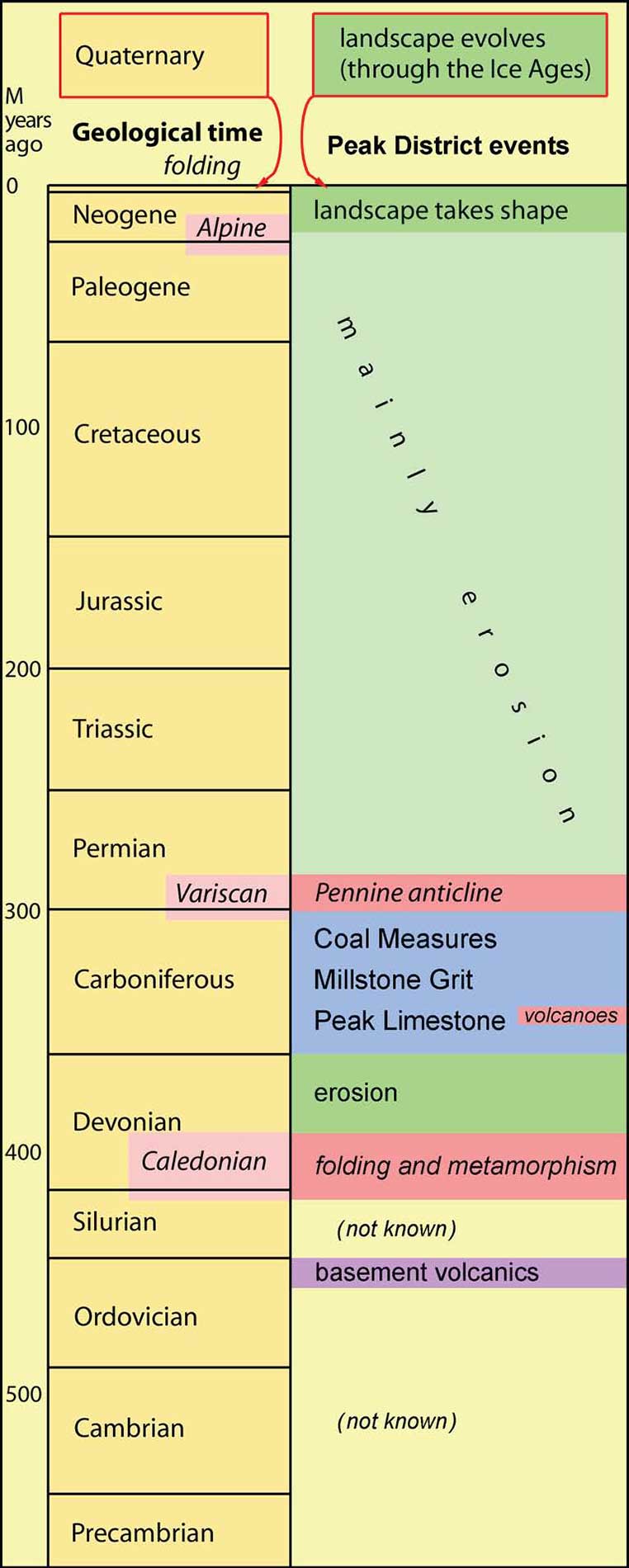

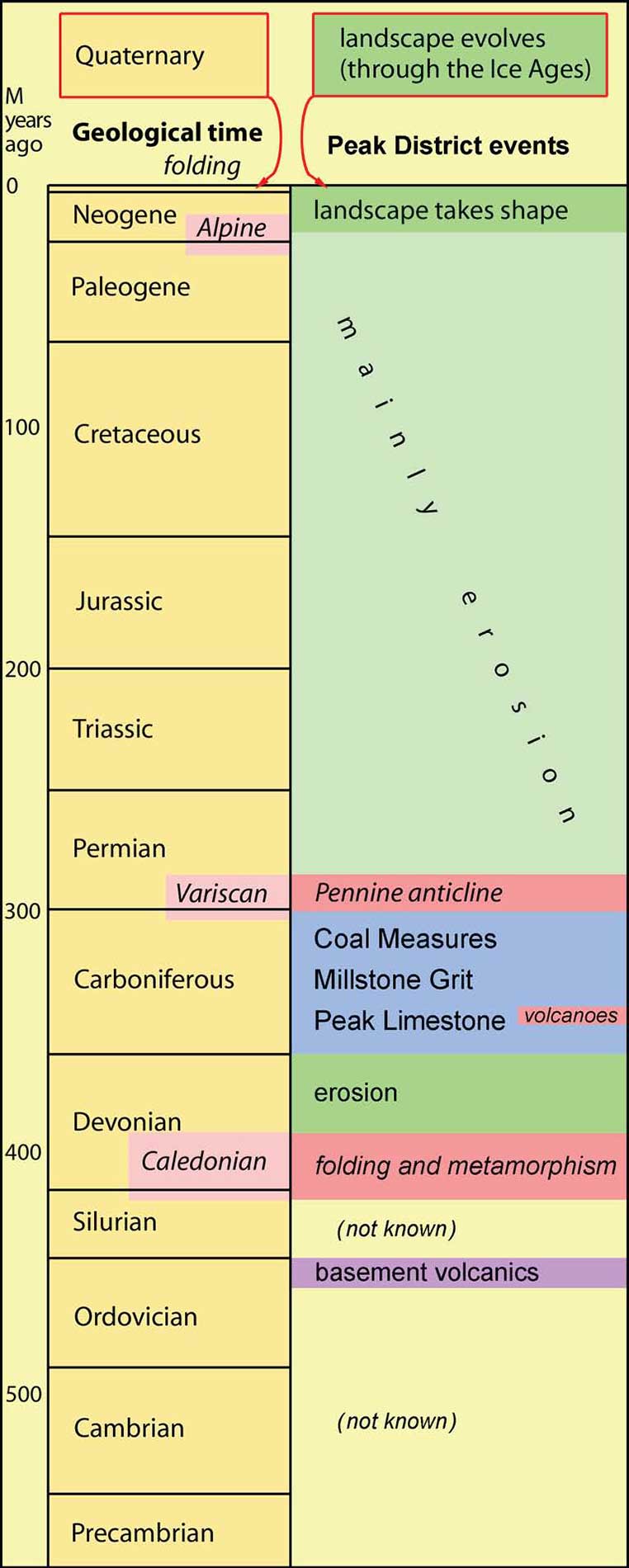

An early phase of the geological history saw a great equatorial lagoon surrounded by reefs atop a structural block known as the Derbyshire Platform, wherein the White Peak limestones were created. These were then buried by huge deltas in which were deposited the Dark Peak gritstones. Next came the uplift and folding of the Derbyshire Dome, followed by erosion that stripped the gritstones away to expose the limestones and form the White Peak. But the limestones were rather different when they reappeared because they had been shot through by mineral deposits during their time of deep burial.

It was thus geology that guided a major factor in the last stage of the evolution of the Peak District landscapes the stage that bears the imprint of mankind. Few landscapes are now without the farming, villages and towns that add to a purely natural world, but the White Peak also has a fascinating heritage from a mining industry that is now almost, but not quite, in the past.

So the Peak District landscapes are not entirely natural unless human beings are accepted as a component of the natural world. Perhaps they should be, even if they are unusual in their ability to impose their own features in a time-span much shorter than those of most geological processes. Quarries, factories and roads may be regarded as negative factors in a landscape, but mankinds impact can be beneficial. The grit edges of the Dark Peak are steep and dramatic because they are actually old quarry faces, and the beautiful open vistas of grassland in the White Peak are free of trees because they are grazed by sheep that have been brought to the area by farmers.

Mankind has also introduced some delightful quirks in the names of features within the Peak District landscapes. The numerous wells, which feature in the annual well dressings, are not wells; to anyone but a local, they are natural springs, but they were important sources of good, clean water in the past. Then there are the hills that are called lows. Their name originates from