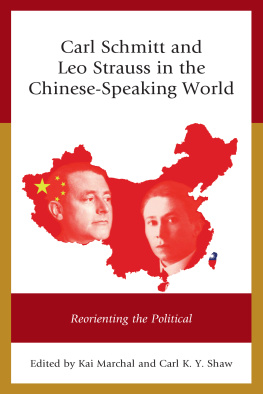

Political Theology

Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty

Carl Schmitt

Translated by George Schwab Foreword by Tracy B. Strong

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

Foreword

The Sovereign and the Exception: Carl Schmitt, Politics, Theology, and Leadership

In memory and appreciation of Wilson Carey McWilliams, 19332005

He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And when you gaze long into an abyss the abyss also gazes into you.

Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

Political Theology is about the nature, and thus about the prerogatives, of sovereign political authority as it develops in the West, about its relation to Western Christianity, and about some of its foremost exponents. While by no means the first writing of Carl Schmitt, it is perhaps the piece that best serves as an introduction to his thought.

Schmitt was aperhaps theleading jurist during the Weimar Republic. In May 1933, he joined the National Socialist German Workers Party (the Nazi Party), the same month as did Martin Heidegger, the leading philosopher in Germany. In November of that year he became the president of the National Socialist Jurists Association. He published several works that were supportive of the Nazi Party, including some that were anti Semitic.1 All did not go smoothly: one tends to forget that there were diverse factions in Nazism, as there are in all political movements, and Schmitt found himself on the losing side of several controversies. Criticized in several official organs, he was protected by Hermann Goering. He remained a member of the Party as well as professor of law at the University of Berlin between 1933 and 1945, and was detained afterwards by the victorious Allies, but never charged with crimes. He died in April 1985.2

1. G. Balakrishnan, The Enemy: An Intellectual Portrait of Carl Schmitt (London: Verso, 2000). Balakrishnan argues that until the last years of the Weimar Republic Schmitt expressed no anti-Semitic views and that during the Nazi period, he became skilled at transforming crude anti-Semitic ideograms into a higher order theoretical discourse. See also the exchange between him and Scheuerman, Down on Law: The complicated legacy of the authoritarian jurist Carl Schmitt in Boston Review (AprilMay 2001).

As early as 1938 and again after World War II, Schmitt was fond of recalling Benito Cereno,one of Herman Melvilles novels,in obvious reference to his choices in 1933 and after.3The novel was translated into German in 1939 and was apparently widely read and discussed in terms of the contemporary political situation.4 The title character in Benito Cereno is the captain of a slave ship that has been taken over by the African slaves. The owner of the slaves and most of the white crew have been killed, although Don Benito is left alive and forced by the slaves leader, Babo, to play the role of captain so as not to arouse suspicion from other ships. Eventually, after a prolonged encounter with the frigate of the American Captain Delano during which the American at first suspects Cereno of malfeasancehe cannot conceive of the possibility that slaves have taken over a shipthe truth comes out: the slaves are recaptured and imprisoned, some executed.

2. See the discussion in my Dimensions of the Debate Around Carl Schmitt, Foreword to Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), xxii, and the references cited there for further discussion of these events.

3. Carl Schmitt, Ex Captivitate Salus: Erfahrungen der Zeit 1945/47 (Cologne: Greven Verlag, 1950), 2277. Thanks to John McCormick for this reference. Let me take this occasion to pay tribute to McCormicks wonderful book on Carl Schmitt, Carl Schmitts Critique of Liberal ism: Against Politics as Technology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), from which I have learned a great deal.

4. Schmitt notes that Benito Cereno, the hero [!!] of Herman Melvilles story, was elevated in Germany to the level of a symbol for the situation of persons of intelligence caught in a mass system. Schmitt, Remarks in response to a talk by Karl Mannheim (19451946), in Ex Captivate Salus. Experiences des annes 19451947. Textes et commentaires, ed. A. Doremus (Paris: Vrin, 2003), 133.

In a letter apparently written on his fiftieth birthday in 1938, Schmitt signed himself as Benito Cereno.5 This passage from the end of the novel, although not one I know Schmitt to have cited explicitly, is in particular relevant:

Only at the end did my suspicions [of you, said Captain Delano to Benito Cereno] get the better of me, and you know how wide of the mark they then proved.

Wide, indeed, said Don Benito, sadly; you were with me all day; stood with me, sat with me, talked with me, looked at me, ate with me, drank with me; and yet, your last act was to clutch for a villain, not only an innocent man, but the most pitiable of all men. To such degree may malign machinations and deceptions impose. So far may even the best men err, in judging the conduct of one with the recesses of whose condition he is not acquainted. But you were forced to it; and you were in time undeceived. Would that, in both respects, it was so ever, and with all men.

I think I understand you; you generalize, Don Benito; and mournfully enough. But the past is passed; why moralize upon it? Forget it. See, yon bright sun has forgotten it all, and the blue sea, and the blue sky; these have turned over new leaves.6

5. Copies of the supposed letter were sent to several people after the War, among them Arnim Mohler, who reprinted it in the publication of his correspondence with Schmitt. (Mohler was the historian-theorist of the conservative revolution in Germany, and, as director of the Carl Siemens-Stiftung after the war, a central intellectual figure of the extreme right in Germany.) Schmitt had apparently wanted this letter to become the epigraph to a reissuing of his book on Hobbes, Der Leviathan in der Staatslehre des Thomas Hobbes. Sinn undFeld schlageines politischen Symbols (Hamburg: Hanseatische Verlaganstalt, 1938), which could then be taken as an esoteric text of resistance to Nazism. Wolfgang Palaver (Carl Schmitt, mythologue politique, in Carl Schmitt, Le Lviathan dans la doctrine de ltat de Thomas Hobbes [Paris: Seuil, 2002], 22024) casts considerable doubt on the complete (though not the partial) truth of this possibility. See also Carl Schmitt, Ex Captivate Salus. Experiences des annes 19451947. Textes et commentaries, ed. A. Doremus (Paris: Vrin, 2003), 209.

6. Hermann Melville, Benito Cereno in Herman Melville, Billy Budd and Other Tales (New York: The New American Library, 1961).

How was it, the captain of the second ship wishes to know, that Benito Cereno was taken in by the evil brewing under his nose? Cereno notes that had he been more acute, it might in fact have cost him his life. Indeed, as he protests, since malign machinations and deceptions impose themselves on all human beings, he had no choice but to play the role in which Babo had cast him. That Schmitt was fond of calling upon the Melville story is complexly revelatory.The captain of a ship might be thought of as the model of what we mean by a sovereign. Yet here we have a story about a man obliged to accept the pose of being in control while actually going along with evil because his safety required it. At the very end of Melvilles story, after Babo and the other slaves have been captured, a shroud falls from the bowsprit of Cerenos erstwhile ship to reveal the skeleton of the slave owner murdered by the revolted slaves, and over it the inscription Follow your leader. Benito Cereno is about, among other things, what being a sovereign or captain is, how one is to recognize one, and the mistakes that can be made when one doesnt.7