Damned

Old Crank

A Self-Portrait of E. W. Scripps

Drawn from his Unpublished Writings

EDITED BY

CHARLES R. MCCABE

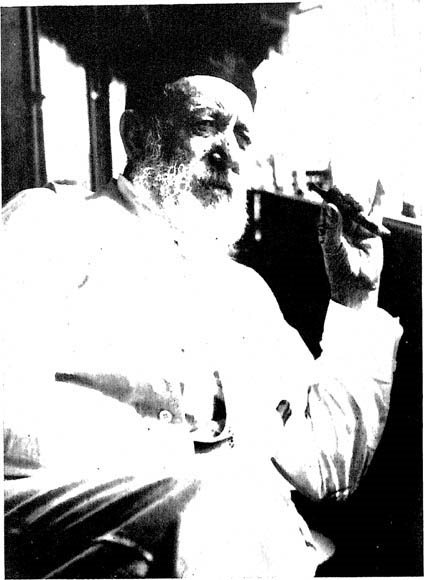

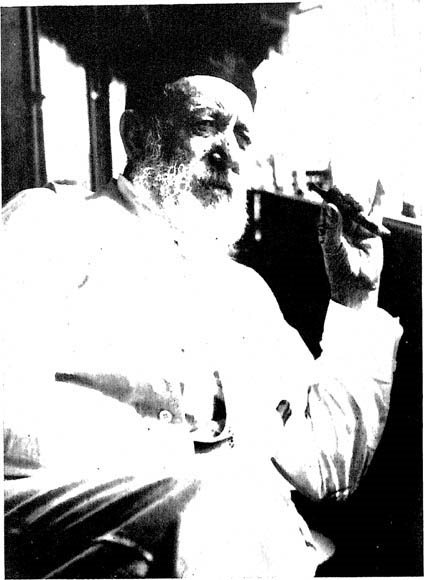

Jerry Clemens Photo

E. W. Scripps on his yacht the Kemah off Singapore in 1924, two years before his death.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTORY NOTE

EDWARD WYLLIS SCRIPPS, the thirteenth child of an English immigrant father, was born in 1854 on a Rushville, Illinois, farm and died of apoplexy aboard his yacht, the Ohio, in Monrovia Bay, Liberia, on a hot spring night in 1926, following a dinner which included energetic conversation with his guest, the American consul, and too many cigars. He died distant from friends and family, surrounded only by employees. He was buried at sea.

The broad lineaments of his career are easy to record. E. W. Scripps served a useful apprenticeship in newspaper work under his half brother, James E. Scripps, founder and owner of the Detroit Evening News.

Early in life he broke with James E., and created from scratch one of the great news enterprises of the world. At his death he left to his only living son the controlling interest in daily newspapers in fifteen states, the United Press Associations, the Newspaper Enterprise Association (N.E.A.), Acme Newsphotos, United Feature Syndicate, and a proliferation of newspaper mechanical and supply properties. Among the newspapers were the Cleveland Press, the Cincinnati Post, the Toledo News-Bee, the Columbus Citizen, the Pittsburgh Press, and the San Francisco News.

Scripps was the principal founder and supporter of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at La Jolla, California; the Scripps Foundation for Research in Population Problems, of Miami University, Miami, Ohio; and the Science News Service of Washington, D.C. During his lifetime the Scripps concern never waxed so great as that of either Hearst or Pulitzer; but five years after his death his successors purchased the choicest of the Pulitzer properties, the New York World. Since then, his properties have shown, in the main, a healthy and steady growth.

Sound management principles and editorial verve, inherited from the founder, have been largely responsible for this growth. Scripps believed in giving his partners and employees their head (up to a point) so long as he retained fifty-one per cent, or control, of the several enterprises. In return for his fifty-one per cent, the concern got his unrelenting editorial integrity and acute, unorthodox business sense.

Scripps was an active newsroom man for only a brief period of his busy life. He became an editorial employee on the Detroit Evening News around 1875, and remained tied to an editorial desk (by gossamer, and with two years out for a health-restoring European trip), until 1890. During this year, after a quarrel with James E., he quit on-the-scene newspapering. A combination of misanthropy, raw nerves and family exacerbations drove him as far away from his kind as was possible without loss of his nationality. He built Miramar Ranch on an arid, windswept mesa about sixteen miles from San Diego, in the final southwest corner of the United States. Save for an interval during World War I, when he attempted to resume active editorial direction of the concern in Washington, D.C., he lived in San Diego until 1920. Then he withdrew again, and even farther. That final withdrawal, so like that of the elder Pulitzer, was to a series of yachts where the owner was truly a potentate. The same pressures that had driven him to San Diego, intensified by age and wavering health, drove him to the sea. To the sea, where he could die decently, and proudly, surrounded not by family or friends, but by people on the payroll.

In 1915, at the request of his sister, Miss Ellen Browning Scripps, E. W. made two attempts at autobiography. They are altogether wooden, and were plainly put down out of a sense of duty; Scripps was always much more at home with ideas than with personal narrative. Yet there were times when he felt strongly that his biography should be written and published. He even chose from among his employees one biographer, but later cast him into exterior darkness because his treatment of materials made available to him was too conventional. His great fear was that a biographer would select only that material which is creditable to me, and that which is conventionally respectable.... In his will he implied an embargo on the publication of his private papers until his grandchildren were grown.

This time has been reached. It is the feeling of the Scripps grandchildren, shared by the editor, that a useful first-person story can be put together from his unpublished autobiographical writings, his letters and his stream of disquisitions. Scripps felt, as did H. G. Wells, that any autobiographical work should be a research into a life rather than an apology for the subjects actions. That standard, plus the desire to provide an interesting narrative, has guided the editor in handling the mass of unpublished material made available by the Scripps family. To provide a more or less connected narrative the material has been, of necessity, freely edited.

Scripps really wrote almost nothing. In his creative period, he dictated everything, and his work shows both the virtues and defects of that method. It is readable and fast-paced. It has great vitality, although it lacks literary quality. Like Henry James, Scripps on occasion got so wound up in his spoken periods that it is difficult to unravel his meaning. He seldom reviewed or corrected any of his writings. The process, not the result, was interesting. They were something he had to get out of him; that was all. When he was writing at Miramar he told his children, around table, what he was up to, and occasionally would read some of his writings to the family. Less frequently he would reach into an old black steel box where he kept his manuscripts heavily locked and declaim to some of his respected cronies like Clarence Darrow, Judge Ben B. Lindsay, or the young Max Eastman. Mostly, however, his writings were something said to secretaries, when the irritation to his active mind became so great that relief was imperative.

Scripps did not commence serious writing until he was in his early fifties. His description of his youth in the Self-Portrait is that of a man already oldvery old, in his view. Agonized self-questionings evident in early letters (in the 1870s) to his sisters Annie and Ellen Browning, are lost in the recollection of the older man. As far as can be judged, he did not want them in the face he wished to show to his children and, inferentially, to the public. It may be felt, without at all impugning E. W.s honesty as an autobiographer, that he was rather less the Roaring Boy of his memory than a lonely, often callow, youth, fighting upstream against a hated humanity. Consider, for instance, his claim that he consumed for many years a gallon of whiskey a daya claim that finds no support either in the alcoholic studies made since his death, or in the experience of topers. But most men are more revealing in the exaggerations and untruths they tell about themselves than when speaking honestly.

The Self-Portrait has confined itself as much as possible to Scripps himself. His relatives and associates enter only when they contribute to the development of his own story. E. W. Scripps fussed a good deal with economics, science and ranching, but of these things there is little here. The