Table of Contents

From the Pages ofThe Origin of Species

No case is on record of a variable being ceasing to be variable under cultivation. (page 18)

I have called this principle, by which each slight variation, if useful, is preserved, by the term of Natural Selection. (page 60)

Nothing is easier than to admit in words the truth of the universal struggle for life. (page 60)

The vigorous, the healthy, and the happy survive and multiply. (page 73)

As buds give rise by growth to fresh buds, and these, if vigorous, branch out and overtop on all sides many a feebler branch, so by generation I believe it has been with the great Tree of Life, which fills with its dead and broken branches the crust of the earth, and covers the surface with its ever branching and beautiful ramifications. (page 114)

Our ignorance of the laws of variation is profound. (page 142)

Natural selection will never produce in a being anything injurious to itself, for natural selection acts solely by and for the good of each. (page 168)

There is no fundamental distinction between species and varieties. (page 225)

The extinction of old forms is the almost inevitable consequence of the production of new forms. (page 274)

This power in fresh-water productions of ranging widely, though so unexpected, can, I think, in most cases be explained by their having become fitted, in a manner highly useful to them, for short and frequent migrations from pond to pond, or from stream to stream. (page 305)

The inumerable [sic] species, genera, and families of organic beings, with which this world is peopled, have all descended, each within its own class or group, from common parents, and have all been modified in the course of descent. (page 361 )

I should infer from analogy that probably all the organic beings which have ever lived on this earth have descended from some one primordial form, into which life was first breathed. (page 380)

When the views entertained in this volume on the origin of species, or when analogous views are generally admitted, we can dimly foresee that there will be a considerable revolution in natural history. (page 380)

It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us. (page 384)

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved. (page 384)

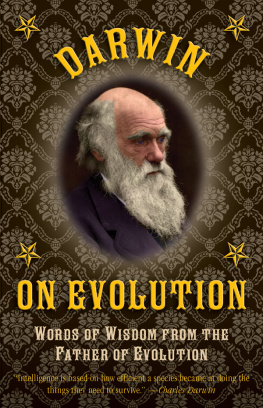

Charles Darwin

Robert Charles Darwin was born in Shrewsbury, England, on February 12, 1809, into a wealthy and highly respected family. His grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, was a doctor and the author of many works, including his well-known Zoonomia, or the Laws of Organic Life, which hinted at a theory of evolution. Charless father, Robert Waring Darwin, was also a prosperous doctor; his mother, Susannah, was the daughter of Josiah Wedgwood, founder of the renowned Wedgwood china factory. The Darwins and Wedgwoods had close and longstanding relations; Charles was to marry his cousin Emma Wedgwood.

In 1825, at age sixteen, Darwin matriculated at Edinburgh University to study medicine. It was at Edinburgh that he became interested in natural history, particularly crustaceans, sea creatures, and beetles. Deciding that medicine was not his vocation, he left Edinburgh in 1827 and entered Christs College, Cambridge University, to study theology. At Cambridge he became friends with J. S. Henslow, a scientifically inclined clergyman and professor of botany. Although Darwin was to graduate from Cambridge with a B.A. in theology, he spent a great deal of his time with Henslow, developing his interest in natural science. It was Henslow who secured a position for Darwin on an exploratory expedition aboard the HMS Beagle.

In December 1831, the year he graduated from Cambridge, Darwin embarked upon that five-year voyage to Africa and South America, acting as a companion to the captain, Robert Fitzroy. Cramped in his cabin and frequently seasick, Darwin nevertheless meticulously gathered specimens and wrote up his ideas. The materials he gathered would lead him to the idea of descent by modification through natural selection. It is conjectured that while in South America Darwin contracted Chagass disease, a tropical illness that became debilitating after the birth of his first child, William, in 1839, for the rest of his life. By the time Darwin returned to London in 1835, many of his letters to scientists, such as geologists Charles Lyell and Adam Sedgwick, had been read before scientific societies and Darwin was a well-known and respected naturalist.

Darwins first published work, an account of his voyage aboard the Beagle entitled Journal of Researches, appeared in 1839. He married the same year; soon after, the family moved to a secluded house at Down, in Kent, where Darwin continued his work toward a book that was to present his theory of evolution, but spent eight years preparing a detailed set of monographs on barnacles in preparation for the larger study.

In 1858, when Darwin was halfway through the writing of the book, naturalist A. R. Wallace sent him a paper that independently laid out the argument for natural selection, in terms very similar to Darwins own. Wallace asked Darwin if he would help get the paper publishedobviously an alarming development, because Darwins work since 1838 had been dedicated to developing the same theory. Darwins scientific friends advised him to gather materials giving evidence of his priority but to have the Wallace paper read before the Linnaean Society, along with a brief account of his own ideas. Immediately after the reading, Darwin began work on an abstract of his larger work; the result, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, was published in 1859. Despite the enormous controversy it generated, Origin was an immense success; it went through six editions in Darwins lifetime.

Darwin devoted the rest of his life to researching and writing scientific treatises, developing and expanding parts of his larger argument. His later works include The variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication (1868) and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872). In 1871 Darwin at last addressed directly implications of his theory for humans: The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex drew on earlier notes, but it also responded to and incorporated ideas on the subject that had filled intellectual and popular journals since the publication of Origin.

Despite ill health, Darwin continued to develop more evidence for his theories through intense studies of a wide range of organic phenomenaclimbing plants, orchids, insectivorous plants, vegetable mold, and worms, to name a few. He died on April 19, 1882, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Next page