Nietzsche Friedrich - Basic Writings of Nietzsche

Here you can read online Nietzsche Friedrich - Basic Writings of Nietzsche full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

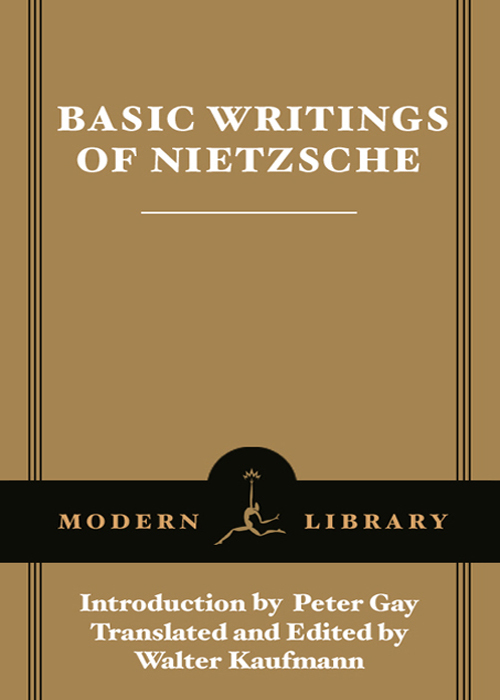

- Book:Basic Writings of Nietzsche

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Basic Writings of Nietzsche: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Basic Writings of Nietzsche" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Nietzsche Friedrich: author's other books

Who wrote Basic Writings of Nietzsche? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Basic Writings of Nietzsche — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Basic Writings of Nietzsche" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

Friedrich Nietzsche was born in 1844 in Rcken (Saxony), Germany. He studied philology at the universities of Bonn and Leipzig, and in 1869 was appointed to the chair of classical philology at the University of Basel, Switzerland. Ill health led him to resign his professorship ten years later. His works include The Birth of Tragedy, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Beyond Good and Evil, On the Genealogy of Morals, The Case of Wagner, Twilight of the Idols, The Antichrist, Nietzsche contra Wagner, and Ecce Homo. He died in 1900. The Will to Power, a selection from his notebooks, was published posthumously.

WALTER KAUFMANN

Walter Kaufmann was born in Freiburg, Germany, in 1921, came to the United States in 1939, and studied at Williams College and Harvard University. In 1947 he joined the faculty of Princeton University, where he became a professor of philosophy. He held many visiting professorships, including Fulbright grants at Heidelberg and Jerusalem. His books include Critique of Religion and Philosophy, From Shakespeare to Existentialism, The Faith of a Heretic, Cain and Other Poems, Hegel, Tragedy and Philosophy, and Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, as well as verse translations of Goethes Faust and Twenty German Poets. He translated all of the books by Nietzsche listed in the biographical note above. He died in 1980.

B ASIC W RITINGS OF N IETZSCHE

PETER GAY

E ver since Nietzsche went insane, and silent, in 1889, as his fame was beginning to spread, his ideas have been most things to most men. Literallyfor on the subject of women, interpretations of his views can hardly differ very much: he was an incurable misogynist. Nor could devout Christians derive any comfort from his writings, which are centrally preoccupied with a destructive analysis of Christianity, its birth, its triumph, its unfortunate longevity. As for principled democrats, they too cannot find much to please them in his work: whatever conclusion one may reach in the end about Nietzsches political thinking, it calls for the distinct separation of an elite and the masses.

But existentialists and nihilists, chauvinists and cosmopolitans, anti-Semites and philo-Semites, Francophiles and professional Teutons, Wagnerites and Brahmsians, nature worshipers and pragmatists, followers of Freud and his critics, have been struggling over his legacy for a century and more. They cannot all be right; in fact, most of them are wrong, dining off a few scraps that Nietzsche had thrown them in a careless mood. But this has not stopped them from arguing.

Yet even in the less than angrily controversial domains, Nietzsches work has been at the mercy of ideologists of all stripes. What is Nietzsches evidence for womens presumed inferiority? What is the reason for his anti-Christian bent? What kind of elite is he calling for? Beyond that, when it comes to the theory of knowledge, is he an absolute skeptic? Do his generalizations about nations support racism? Why does he do his utmost to distance himself from the Germany of his time? And what of Wagner, first his friend and then his enemy? The questions pile up and there are all too many answers canceling each other out.

There is of course nothing new or unexpected concerning battles about the meaning of a thinkers work. One recalls Plato, Machiavelli, Hobbes, Rousseau, Hegel, and the debates that their real message has generated across the centuries. But Nietzsches thought has been particularly susceptible to often envenomed controversies, generating incompatible claims about the influence of that thought not only on recent philosophy, but also, and more portentously, on recent politics.

Why? As readers of this volume can readily discover for themselves, Nietzsche was a superb stylist. Writing as trenchantly as he did, he was the antithesis of the traditional German professor, with his heavy vocabulary, serpentine sentences, and convoluted reasoning. But, paradoxical as it may sound, Nietzsche wrote too well for his own good. He coined memorable aphorisms and seductive locutions that have been used against himby and large unfairly. Even if (indeed, especially if) we do not know much about Nietzsche, we are likely to remember his terms: the blond beast, which can easily be taken as a sample of Aryan megalomania, or the bermensch, usually translated as Superman, thus awakening images of Clark Kent donning his cape. And what of his heartless, condescending observation, Everything about woman has a solution: it is called pregnancy? Though such Nietzschean views leave an unpleasant aftertaste, most can be satisfactorily clarified by the context and the dominant style of thinking that pervades his thought. But this means that one can judge Nietzsche only after reading him, not before.

The fact is that many philosophers in many countries now read him, and with care; in all probability, Nietzsche is the most studied German thinker in English-, French-, and Italian-speaking cultures. His ability to turn accepted moral certitudes on their head, his skeptical questioning of confident realists who see the outside world as easily accessible to the investigator, and his astonishing psychological insights that have made it tempting to see Freud as his disciple (which he was not)all this, as we have seen, makes him appealing to minds attached to the most varied systems. In some quarters, indeed, among some literary critics, he has become something of a fad. Postmodernists intent on showing that there is no stable world out there, and that everything is a social construct, have taken comfort from a remark of Nietzsches, Truths are a useless fiction. Well, of course one can easily find statements in Nietzsche that uphold the opposite, or generate doubts about this statement. A faithful (but not slavish) reader of Nietzsche must acknowledge that one reason why there is so much debate about Nietzsches meaning is that he occasionally contradicts himself. Hence the way to defend a certain position on Nietzsche is not to rely on a single aphorism, but to penetrate to the central significance of the texts in which the passage is embedded.

There is another, a historical, reason why Nietzsche has aroused so much rancor across the twentieth century, especially after the outbreak of the First World War: his presumed advocacy of a brutal Teutonic philosophy of life that explained the alleged conduct of the German armies during the war.

After January 30, 1933, this reproach grew even fiercer. On that day, Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany, and with that, the charge that Nietzsche had inspired much of the Nazis murderous ideology became widespread and seemed utterly plausible. In Germany itself, after that fateful date, servile commentators, knowing what would please Joseph Goebbels, did their utmost to claim Nietzsche for Hitlers movement. This was not so easily done; it necessitated explaining away the passages in Nietzsche that could not possibly be reconciled with Hitlerian dogma, but which were present, the authors had to admit, in Nietzsches works. One way of dealing with this dilemma was to falsify his texts, or to take some of Nietzsches comments out of context. Thus, his infrequent anti-Jewish remarks, normally surrounded by declarations of admiration for the Jews, could be stripped of this praise, so that they could misdescribe Nietzsches philo-Semitism as anti-Semitism. The fact is that it was particularly the German anti-Semites of his own time that Nietzsche most despised. In the United States, a not dissimilar viewNietzsche the prophet of the Third Reichthough of course less infected with propaganda, carried the day. The one or two more responsible interpreters who knew their Nietzsche better than this were swamped in the hostile consensus.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Basic Writings of Nietzsche»

Look at similar books to Basic Writings of Nietzsche. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Basic Writings of Nietzsche and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.