Alexandra Horowitz - Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know

Here you can read online Alexandra Horowitz - Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: Scribner, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know

- Author:

- Publisher:Scribner

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

WHAT DOGS SEE, SMELL, AND KNOW

ALEXANDRA HOROWITZ

SCRIBNER

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2009 by Alexandra Horowitz, with illustrations by the author

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Scribner hardcover edition September 2009

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales: 1-866-506-1949 or business@simonandschuster.com.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com .

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2008045842

ISBN 978-1-4165-8340-0

ISBN 978-1-4165-8827-6 (eBook)

To the dogs

Outside of a dog, a book is mans best friend.

Inside of a dog, its too dark to read.

ATTRIBUTED TO GROUCHO MARX

INSIDE OF A DOG

First you see the head. Over the crest of the hill appears a muzzle, drooling. It is as yet not visibly attached to anything. A limb jangles into view, followed in unhasty succession by a second, third, and fourth, bearing a hundred and forty pounds of body between them. The wolfhound, three feet at his shoulder and five feet to his tail, spies the long-haired Chihuahua, half a dog high, hidden in the grasses between her owners feet. The Chihuahua is six pounds, each of them trembling. With one languorous leap, his ears perked high, the wolfhound arrives in front of the Chihuahua. The Chihuahua looks demurely away; the wolfhound bends down to Chihuahua level and nips her side. The Chihuahua looks back at the hound, who raises his rear end up in the air, tail held high, in preparation to attack. Instead of fleeing from this apparent danger, the Chihuahua matches his pose and leaps onto the wolfhounds face, embracing his nose with her tiny paws. They begin to play.

For five minutes these dogs tumble, grab, bite, and lunge at each other. The wolfhound throws himself onto his side and the little dog responds with attacks to his face, belly, and paws. A swipe by the hound sends the Chihuahua scurrying backward, and she timidly sidesteps out of his reach. The hound barks, jumps up, and arrives back on his feet with a thud. At this, the Chihuahua races toward one of those feet and bites it, hard. They are in mid-embracethe hound with his mouth surrounding the body of the Chihuahua, the Chihuahua kicking back at the hounds facewhen an owner snaps a leash on the hounds collar and pulls him upright and away. The Chihuahua rights herself, looks after them, barks once, and trots back to her owner.

These dogs are so incommensurable with each other that they may as well be different species. The ease of play between them always puzzled me. The wolfhound bit, mouthed, and charged at the Chihuahua; yet the little dog responded not with fright but in kind. What explains their ability to play together? Why doesnt the hound see the Chihuahua as prey? Why doesnt the Chihuahua see the wolfhound as predator? The answer turns out to have nothing to do with the Chihuahuas delusion of canine grandeur or the hounds lack of predatory drive. Neither is it simply hardwired instinct taking over.

There are two ways to learn how play worksand what playing dogs are thinking, perceiving, and saying: be born as a dog, or spend a lot of time carefully observing dogs. The former was unavailable to me. Come along as I describe what Ive learned by watching.

I am a dog person.

My home has always had a dog in it. My affinity for dogs began with our family dog, Aster, with his blue eyes, lopped tail, and nighttime neighborhood ramblings that often left me up late, wearing pajamas and worry, waiting for his midnight return. I long mourned the death of Heidi, a springer spaniel who ran with excitementmy childhood imagination had her tongue trailing out of the side of her mouth and her long ears blown back with the happy vigor of her runright under a cars tires on the state highway near our home. As a college student, I gazed with admiration and affection at an adopted chow mix Beckett as she stoically watched me leave for the day.

And now at my feet lies the warm, curly, panting form of PumpernickelPumpa mutt who has lived with me for all of her sixteen years and through all of my adulthood. I have begun every one of my days in five states, five years of graduate school, and four jobs with her tail-thumping greeting when she hears me stir in the morning. As anyone who considers himself a dog person will recognize, I cannot imagine my life without this dog.

I am a dog person, a lover of dogs. I am also a scientist.

I study animal behavior. Professionally, I am wary of anthropomorphizing animals, attributing to them the feelings, thoughts, and desires that we use to describe ourselves. In learning how to study the behavior of animals, I was taught and adhered to the scientists code for describing actions: be objective; do not explain a behavior by appeal to a mental process when explanation by simpler processes will do; a phenomenon that is not publicly observable and confirmable is not the stuff of science. These days, as a professor of animal behavior, comparative cognition, and psychology, I teach from masterful texts that deal in quantifiable fact. They describe everything from hormonal and genetic explanations for the social behavior of animals, to conditioned responses, fixed action patterns, and optimal foraging rates, in the same steady, objective tone.

And yet.

Most of the questions my students have about animals remain quietly unanswered in these texts. At conferences where I have presented my research, other academics inevitably direct the postlecture conversations to their own experiences with their pets. And I still have the same questions Id always had about my own dogand no sudden rush of answers. Science, as practiced and reified in texts, rarely addresses our experiences of living with and attempting to understand the minds of our animals.

In my first years of graduate school, when I began studying the science of the mind, with a special interest in the minds of non-human animals, it never occurred to me to study dogs. Dogs seemed so familiar, so understood. There is nothing to be learned from dogs, colleagues claimed: dogs are simple, happy creatures whom we need to train and feed and love, and that is all there is to them. There is no data in dogs. That was the conventional wisdom among scientists. My dissertation advisor studied, respectably, baboons: primates are the animals of choice in the field of animal cognition. The assumption is that the likeliest place to find skills and cognition approaching our own is in our primate brethren. That was, and remains, the prevailing view of behavioral scientists. Worse still, dog owners seemed to have already covered the territory of theorizing about the dog mind, and their theories were generated from anecdotes and misapplied anthropomorphisms. The very notion of the mind of a dog was tainted.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

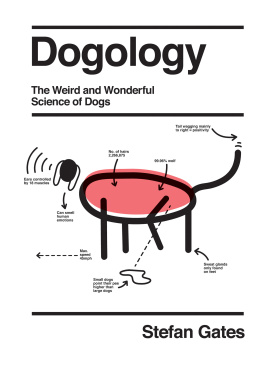

Similar books «Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know»

Look at similar books to Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.