To the memory of my mother and father

I am indebted to many friends who offered their timely suggestions and corrections during the preparation of this book. I would especially like to thank Mark Baillie, Helen Crisp, Humayun Khan, Duncan McAra, the editorial team at Sutton Publishing and the research staff at the Royal Geographical Society, the Royal Archives and the Royal Society for Asian Affairs.

C ONTENTS

Chapter 1 |

Chapter 2 |

Chapter 3 |

Chapter 4 |

Chapter 5 |

Chapter 6 |

1. Ahmad Shah Durrani.

2. Lord Ellenborough.

3. Sir William Macnaghten, British Envoy to Kabul.

4. The Governor General Lord Auckland.

5. Shah Shuja ul Mulk.

6. The fortress of Ghazni.

7. Akbar Khan.

8. Lady Florentia Sale.

9. British hostages in captivity.

10. Major Eldred Pottinger.

11. The house where Major-General Elphinstone died.

12. Captain Thomas Souter.

MAPS

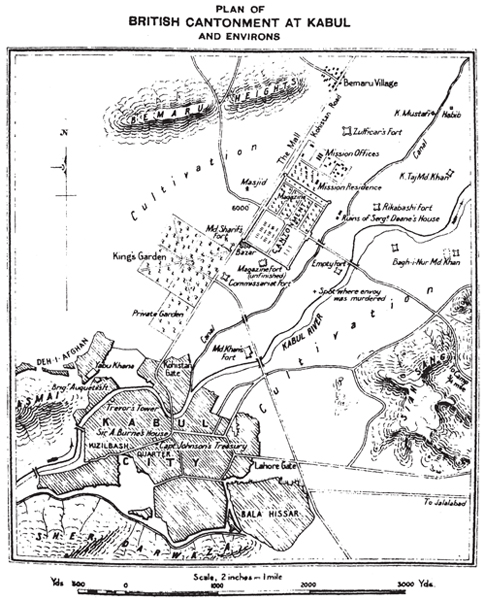

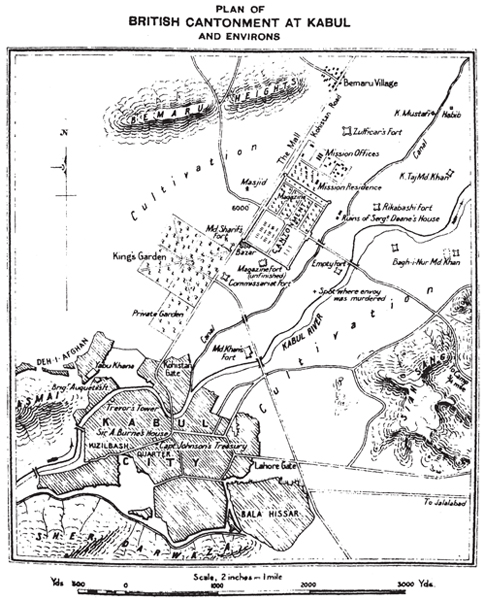

The British cantonment at Kabul.

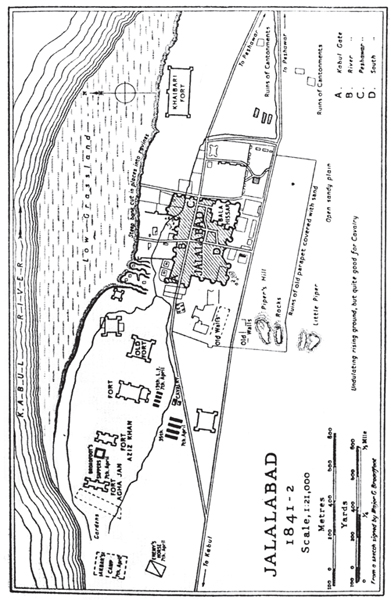

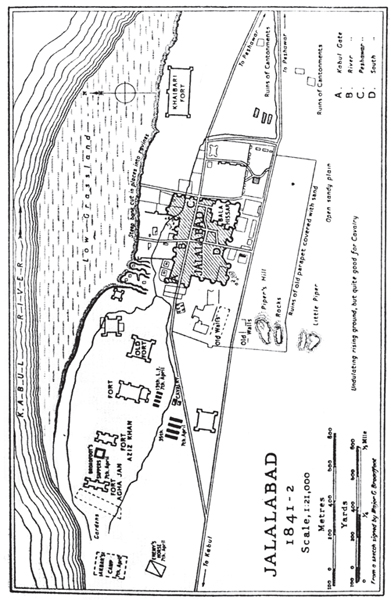

Jalalabad during the siege by Akbar Khan.

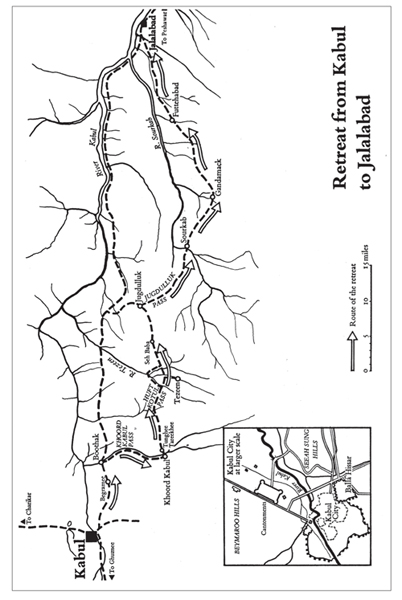

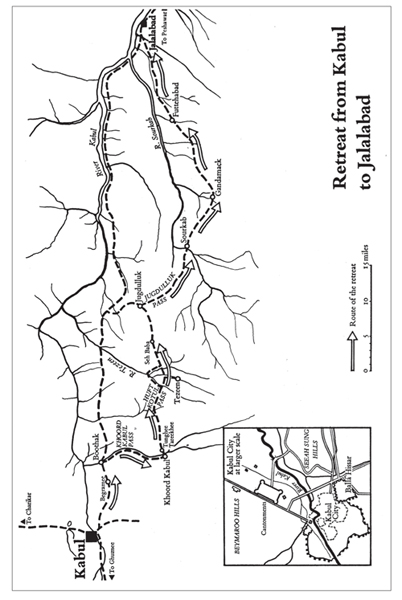

The retreat from Kabul to Jalalabad.

General Sir David Richards KCB CBE DSO

Its coming to a crash in Central Asia. I daresay itll be staved off for the present, but it must come to something hereafter, to be decided whether England or Russia should reign there, both pushing from different sides.

Prime Minister Viscount Melbourne to

Queen Victoria, 7 April 1839

E ntertaining, easy to read, yet accurate and authoritative, I wish this excellent book had been published before I deployed to Afghanistan in May 2006 to command NATOs International Security and Assistance Force. While Jules Stewart vividly recounts a sorry tale in British military and diplomatic history that took place 165 years ago, the lessons for the international communitys effort in Afghanistan today are pertinent and timeless.

I have read other descriptions of Great Britains failed attempt to impose its will on Afghanistan in 18412 but none capture what happened, or the enduring personalities and atmospherics of the country, as well as Stewart does. Despite being separated by so many years from Macnaghten and Elphinstone, repeatedly I found myself chuckling in recognition of an event, tactic or person and thinking nothings changed! Even knowing the country as well as I now do, the book sheds fresh and authoritative light on what makes Afghanistan and its people tick. Repeatedly my forerunners in that beautiful but blighted country misjudged its leaders, underestimating a fierce resolve to run their own lives. Too rarely did they seek properly to understand the ruthless nature of their opponents or the tribal loyalties and customs that determine responses to unfolding events. While certainly trying to do much better in 2008, in the event todays diplomats and soldiers too frequently make the same errors.

Should the history of the First Afghan War stand as a lesson for today? In many respects the answer must be yes. The confused aims, the petty squabbling between vain people, the inability to act with a sense of urgency and in a manner that accords with the psyche of the people they seek to help, all these remain common threads today. As is the disconnection between military and political activity, well brought out by Stewart when he quotes George Lawrences letter to The Times on the prospects for the Second Afghan War: a new generation has arisen which, instead of profiting by the solemn lessons of the past, is willing and eager to embroil us in the affairs of that turbulent and unhappy country. Although military disasters might be avoided, an advance now, however successful in a military point of view, would not fail to turn out politically as useless. Resolving this conundrum remains the biggest issue for todays policy makers, one aggravated by the inherently disunited nature of a multinational campaign. While military gains are made daily, in the absence of well-resourced, coherent and timely political and economic measures, they may count for nothing.

In other respects, though, I believe todays war is different from those that preceded it, and here I appear to disagree with Stewart. This war is not a British-only affair. It is fought at the behest of the Afghan government, UN mandated and actively supported by over fifty of the worlds richest nations. After a hesitant start, lessons have been learnt. A greater sense of urgency and better coordination is now evident in the application of both military and non-military measures. Huge amounts of money are entering the country and beginning to have real effect. Importantly, reliable polling in late 2007 tells us that well over 80 per cent of the Afghan population still wants its democratically elected government and the international community to succeed. The Taliban are supported by less than 10 per cent of the population. It is for this reason that I quote again from Jules Stewarts thought-provoking final chapter. He says: The Afghans will always win, inferring that they and the foreigner are always on opposite sides. While the lessons of history tell us that we do not have forever, in this Afghan war the Afghan people and the foreigner are for now on the same side. The trick will be to ensure that we remain so through a visionary and generous strategy that reflects the reality and needs of Afghan culture. InshAllah!

Plan of the British cantonment at Kabul.

Jalalabad during the siege by Akbar Khan.

The retreat of the Army of the Indus from Kabul to Jalalabad (Authors Collection)

Chapter 1

O n a summer evening in 1839, a young Cossack officer by the name of Captain Yan Vikevitch wearily climbed the steps to his St Petersburg hotel room. Vikevitch lit the coal fire in his room, ignoring the muggy heat that rose from the River Neva below his window. The gallant young officer then reflected on what he would say to his friends in the farewell letter he was about to write. Once the logs in the grate were burning brightly, Vikevitch gathered his expedition reports and diaries, and one by one, consigned them to the flames. He then took pen in hand and filled several sheets of coarse Russian notepaper with declarations of remorse over the failure of his mission to Afghanistan, as agent of Tsar Nicholas I, and the humiliation he had suffered only hours before at the hands of the Russian foreign minister, Count Karl Nesselrode. When he finished, the 30-year-old Lithuanian-born aristocrat laid down his pen, pulled his service revolver from its leather holster and blew his brains out.

One would not have considered the death of a relatively obscure tsarist army officer, no matter how tragic the circumstances, the sort of incident to visit disaster on a great empire. Yet Vikevitchs suicide figured in the train of occurrences of that fateful year, which were swiftly to sweep the Raj to the brink of catastrophe and trigger the greatest single military debacle the British ever suffered in India.

Next page