JUMPERS FOR

GOALPOSTS

HOW FOOTBALL SOLD ITS SOUL

ROB SMYTH & GEORGINA TURNER

For our Dads

INTRODUCTION

HOW FOOTBALL SOLD ITS SOUL

O f course, youll have to define the soul of football, they said. Balls.

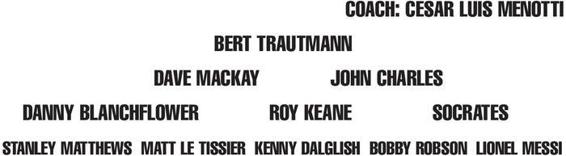

Orange ones, on snow covered pitches. Thats the sort of image that springs up as the mind casts around for the essence of the game we fell in love with before anyone knew better. The sort of stuff Julie Andrews could have sung a song about, while chucking small children under the chin. Its virtually impossible to grasp the notion of footballs soul tightly enough to hold it still, yet lightly enough to appreciate its contours and colours in your hands. We were certain, though, that we could assemble a team whose attributes combined to do some of the explaining for us, a sort of Soul of Football XI. We have laid the team out in a loose 2-3-5 formation. This is absolutely because of our belief in the innocent charm of such a formation, and has nothing to do with the fact that most of the natural choices were midfielders and attackers. Ahem. Were also conscious that most of the players included are British or Anglicised; were not xenophobes, honest.

Bert Trautmann

Physical courage has always been an enormous part of football, whether its Diego Maradona repeatedly demanding possession despite the chilling menace of some of the most malevolent swine ever to roam the green, or people who have played on with broken arms, collarbones and legs. But the Manchester City goalkeeper Bert Trautmann took that to a whole new level when he played in an FA Cup final with a broken neck. A broken neck. A broken neck . A broken bloody neck! Its the single most jaw-dropping act of bravery in football, and fitting for a man who covered the full spectrum of courage. When he arrived at Manchester City in 1949, having grown up in Hitlers Germany and been part of the Luftwaffe , over 20,000 protested at his signing. Trautmann won them over with his heroism, his decency he actively sought out Manchesters Jewish community to discuss his background and, of course, his brilliance in goal. Matt Busby told his Manchester United players never to look up when they played against Trautmann; the moment he caught their eyes, he would decipher precisely what they were planning to do.

Dave Mackay

Mackay is the incarnation of the strong, silent type. He was a player who went about his business without fanfare or melodrama; who simply got on with his job because it was, well, his job. Even when he suffered serious injury he would barely react. Mackays courage was exceptional by any standards, and he was the sort of leader to whom a crowd could relate and aspire: a man of iron will but also dignity and fairness. He upheld the unspoken code of honour between footballers: that they would compete with rare intensity, but that they would never cheat or attempt to injure each other. A lament for the potential extinction of Mackays type applies not just to football but to masculinity itself.

John Charles

A giant of the game in every respect, Charles was known as Il Gigante Buono (The Gentle Giant) during his time at Juventus. He was a tough man but scrupulously fair, never being booked or sent off during his career. During his first Turin derby, in 1957, Charles collided with a defender as he was about to shoot; when the defender collapsed to the floor, Charles eschewed a one-on-one and put the ball out of play. I only had the goalie to beat but it didnt seem fair, said Charles. I put the ball out for a shy so the fella could be looked after. That night he heard tooting outside his villa, and saw a number of Torino fans waving scarves. He asked them what was going on, and was told that they wanted to thank him, so Charles invited them in about 20 all told, and by the time they left in the early hours of the morning they had drunk all my wine. It was a typical gesture from one of sports true gentlemen. John wasnt only one of the greatest footballers who ever lived, said Sir Bobby Robson. He was one of the greatest men ever to play the game.

Danny Blanchflower

Blanchflower, captain of Spurs legendary Double-winning side of 1960/61, embodies the fading belief that glory is more important than victory, and that the way you do something is more important than what you do. The great fallacy is that the game is first and last about winning. Its nothing of the kind. The game is about glory, he said. Its about doing things in style, with a flourish; its about going out to beat the other lot, not waiting for them to die of boredom. Blanchflower, a tactical visionary, also had no interest in the extraneous ego-massage that football offered: he became the first person to turn down the chance to appear on This Is Your Life , imperiously walking away from Eamonn Andrews live on air. He also refused to compromise his punditry during a spell in America, when he was told to be positive rather than honest for fear of offending. The gentleman was never for turning.

Roy Keane

Those who remember Keanes appalling, indefensible challenge on Alf-Inge Haaland, not to mention his furious haranguing of team-mates and opponents, might legitimately dispute his inclusion in a Soul of Football XI. Yet Keane is an almost uniquely complex character, and other sides of his multi-faceted persona are very much in keeping with the themes of this book. The most important is his searing honesty, so utterly refreshing in a sport increasingly defined by disingenuousness. It was that, as much as anything, that made his 2002 autobiography one of the greats of its genre. Other admirable elements of Keanes nature include the forensic intelligence he brings to his work; the fact he cares about football sufficiently to rage so furiously against the dying of its light; his peerless bullshit detector; his rejection of the corporate and celebrity cultures that surround modern football; and his lyrical capacity to sum those up in a pithy phrase, as he did with talk of prawn sandwiches and Rolex culture.

Scrates

There are very few jobs as cool as that of the professional footballer, and so it seems like a fair trade to ask in return that our footballers should be cool yet so few are these days. There is certainly nobody to compare to Scrates, the effortlessly chic Brazilian who captained their wonderful 1982 and 1986 World Cup sides. Scrates looked the part, with a languorous gait and a big, enviable beard. Even the sweat patch on his Topper shirt, the result of the fierce heat during the Mexico World Cup, somehow looked good. He soaked his shirts even though he was not exactly the most vigorous of footballers: Scrates preferred the art of football, passing the ball rhythmically around the field. Not trying too hard was the essence of his cool, too: there was no posturing and very little ostentatiousness (well forgive him showy penalties in 1986). He was a heavy smoker and drinker during his playing days, is a doctor of medicine and one of the smartest men to play the game. As with everything else, he wore intelligence lightly. Its one of the many reasons that he was the coolest of them all.