The Complete Works of

IAMBLICHUS

(c. AD 245 c. 325)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2021

Version 1

Browse Ancient Classics

Explore Philosophy at Delphi Classics

The Complete Works of

IAMBLICHUS OF CHALCIS

By Delphi Classics, 2021

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Iamblichus

First published in the United Kingdom in 2021 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2021.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 80170 021 4

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

The Translations

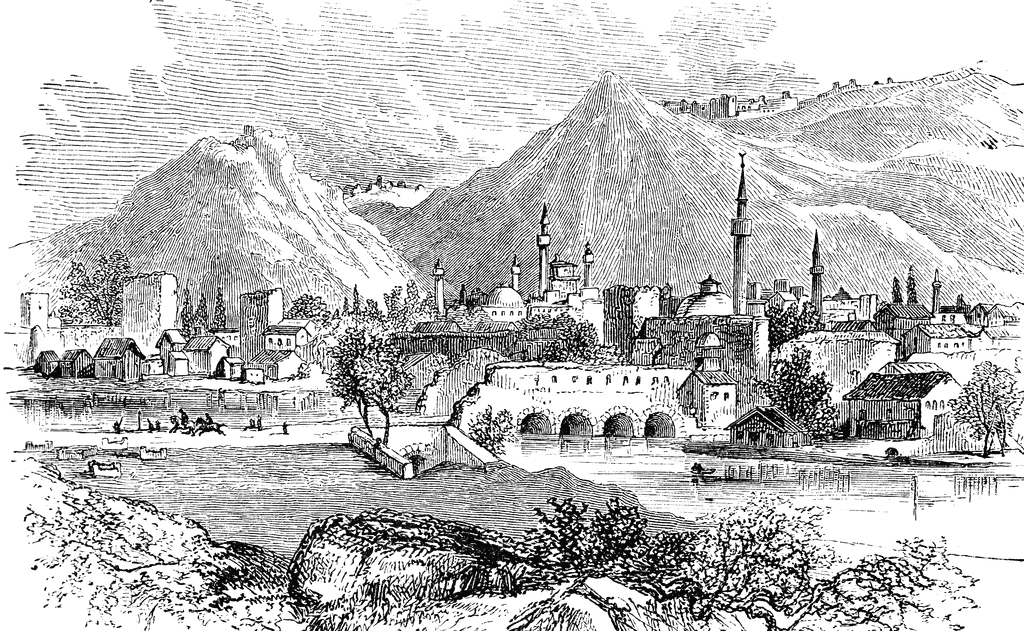

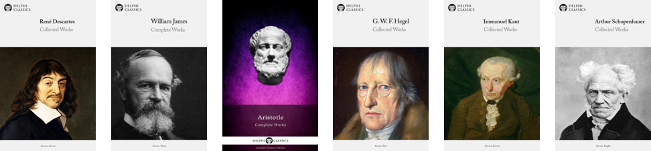

The ancient Roman road connecting Antioch and Chalcis Iamblichus was born at Chalcis (modern day Qinnasrin, northern Syria). The town was situated 15 miles south west of Aleppo on the west bank of the Queiq River. Iamblichus was the son of a rich and illustrious family, and he is said to have been the descendant of several priest-kings of the Arab Royal family of Emesa.

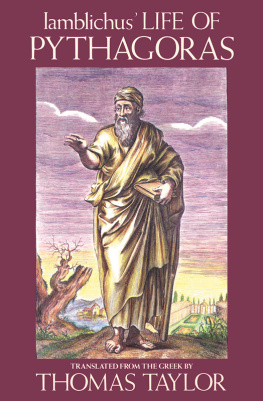

Life of Pythagoras

Translated by Thomas Taylor, 1818 and Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie, 1919

CONTENTS

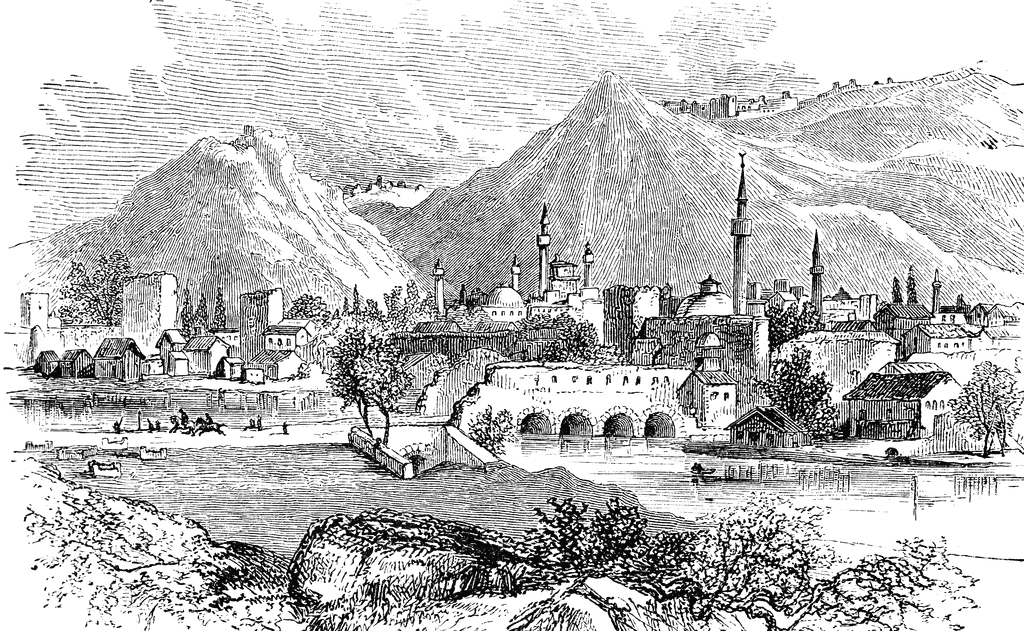

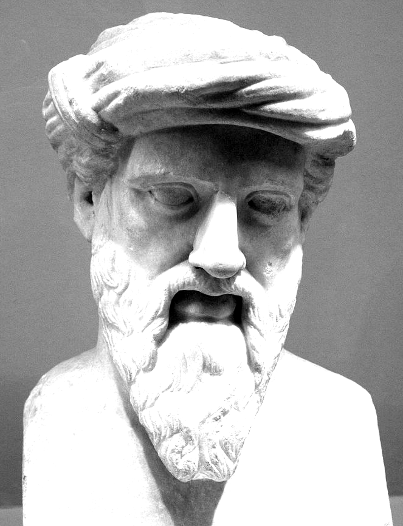

Pythagoras of Samos (c. 570 c. 495 BC) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism this bust is a Roman copy of a Greek original from the 2nd-1st century BC.

Thomas Taylor Translation, 1818

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION.

When it is considered that Pythagoras was the father of philosophy, authentic memoirs of his life cannot fail to be uncommonly interesting to every lover of wisdom, and particularly to those who reverence the doctrines of Plato, the most genuine and the best of all his disciples. And that the following memoirs of Pythagoras by Iamblichus are authentic, is acknowledged by all the critics, as they are for the most part obviously derived from sources of very high antiquity; and where the sources are unknown, there is every reason to believe, from the great worth and respectability of the biographer, that the information is perfectly accurate and true.

Of the biographer, indeed, Iamblichus, it is well known to every tyro in Platonism that he was dignified by all the Platonists that succeeded him with the epithet of divine ; and after the encomium passed on him by the acute Emperor Julian, that he was posterior indeed in time, but not in genius, to Plato , all further praise of him would be as unnecessary, as the defamation of him by certain modern critics is contemptible and idle. For these homonculi looking solely to his deficiency in point of style, and not to the magnitude of his intellect, perceive only his little blemishes, but have not even a glimpse of his surpassing excellence. They minutely notice the motes that are scattered in the sunbeams of his genius, but they feel not its invigorating warmth, they see not its dazzling radiance.

Of this very extraordinary man there is a life extant by Eunapius, the substance of which I have given in my History of the Restoration of the Platonic Theology, and to which I refer the English reader. At present I shall only select from that work the following biographical particulars respecting our Iamblichus: He was descended of a family equally illustrious, fortunate, and rich. His country was Chalcis, a city of Syria, which was called Cle. He associated with Anatolius who was the second to Porphyry, but he far excelled him in his attainments, and ascended to the very summit of philosophy. But after he had been for some time connected with Anatolius, and most probably found him insufficient to satisfy the vast desires of his soul, he applied himself to Porphyry, to whom (says Eunapius) he was in nothing inferior, except in the structure and power of composition. For his writings were not so elegant and graceful as those of Porphyry: they were neither agreeable, nor perspicuous; nor free from impurity of diction. And though they were not entirely involved in obscurity, and perfectly faulty; yet as Plato formerly said of Xenocrates, he did not sacrifice to the Mercurial Graces . Hence he is far from detaining the reader with delight, who merely regards his diction; but will rather avert and dull his attention, and frustrate his expectation. However, though the surface of his conceptions is not covered with the flowers of elocution, yet the depth of them is admirable, and his genius is truly sublime. And admitting his style to abound in general with those defects, which have been noticed by the critics, yet it appears to me that the decision of the anonymous Greek writer respecting his Answer to the Epistle of Porphyry,

Iamblichus shared in an eminent degree the favor of divinity, on account of his cultivation of justice; and obtained a numerous multitude of associates and disciples, who came from all parts of the world, for the purpose of participating the streams of wisdom, which so plentifully flowed from the sacred fountain of his wonderful mind. Among these was Sopater the Syrian, who was most skilful both in speaking and writing; Eustathius the Cappadocian; and of the Greeks, Theodorus and Euphrasius. All these were excellent for their virtues and attainments, as well as many other of his disciples, who were not much inferior to the former in eloquence; so that it seems wonderful how Iamblichus could attend to all of them, with such gentleness of manners and benignity of disposition as he continually displayed.

Next page