A Treasury of Schweitzer

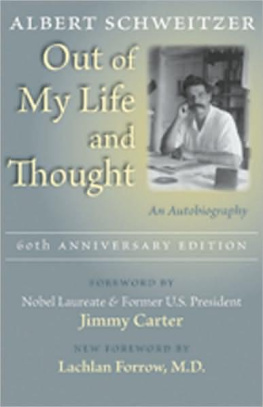

Albert Schweitzer

Edited by Thomas Kiernan

Editors Preface

It is more than fifty years since Albert Schweitzer went to Lambarn, in what is now Gabon, to practice medicine and found a hospital. In that time he has become a universal symbol of altruism, self-sacrifice and dedication.

Within the more recent past, however, there has developed a highly vocal coterie of critics of Dr. Schweitzer, both in and outside Africa. With the emergence of the new Africa, where self-determination is an at least partially realized fact and colonial rule is fast disintegrating, the mission of Schweitzer has been brought under question. While Schweitzers medical methods and philosophy were considered suitable for colonial Africa, they are now adjudged hopelessly anachronistic.

However valid much of the criticism may be, it cannot be forgotten that when Schweitzer first arrived in Lambarn in 1913 he ran real risks, endured real hardships, and made a real contribution to the health and welfare of those among whom he chose to live. It must be remembered that Schweitzer, through his continuing devotion to the principles he set out to follow, became one of the greatest humanitarians of our time, and that, although criticisms concerning his medical methods may, from a medical point of view, be valid, his reputation as a humanitarian cannot be tarnished.

Because of Schweitzers fame as a medical missionary, other, equally important aspects of his life are not so well known. Schweitzer was, among other things, an accomplished musician, an authority on the Bible (his early investigations of the New Testament set the pace for later, more esoteric, Biblical studies), an expert on animals and plant life, and a thinker whose concern with the problems of the human spirit and whose methods of expressing this concern raised him to the stature of one of our foremost philosophers.

As this book went to press, the sad news came of the death of Albert Schweitzer. The mortal man has passed from us but his ideas and vision are immortal.

Thomas Kiernan

Contents

A Treasury of Albert Schweitzer

Feeling for Animal Life

As far back as I can remember I was saddened by the amount of misery I saw in the world around me. Youths unqualified joie de vivre, I never really knew, and I believe that to be the case with many children, even though they appear outwardly merry and quite free from care.

One thing that specially saddened me was that the unfortunate animals had to suffer so much pain and misery. The sight of an old limping horse, tugged forward by one man while another kept beating it with a stick to get it to the knackers yard at Colmar, haunted me for weeks.

It was quite incomprehensible to methis was before I began going to schoolwhy in my evening prayers I should pray for human beings only. So when my mother had prayed with me and had kissed me good night, I used to add silently a prayer that I had composed myself for all living creatures. It ran thus: O, heavenly Father, protect and bless all things that have breath; guard them from all evil, and let them sleep in peace.

[ I ]

A deep impression was made on me by something which happened during my seventh or eighth year. A friend and I had with strips of India rubber made ourselves catapults, with which we could shoot small stones. It was spring and the end of Lent, when one morning my friend said to me, Come along, lets go on to the Rebberg and shoot some birds. This was to me a terrible proposal, but I did not venture to refuse for fear he should laugh at me. We got close to a tree which was still without any leaves, and on which the birds were singing beautifully to greet the morning, without showing the least fear of us. Then stooping like a Red Indian hunter, my companion put a bullet in the leather of his catapult and took aim. In obedience to his nod of command, I did the same, though with terrible twinges of conscience, vowing to myself that I would shoot directly he did. At that very moment the church bells began to ring, mingling their music with the songs of the birds and the sunshine. It was the Warning-bell, which began half an hour before the regular peal-ringing, and for me it was a voice from heaven. I shooed the birds away, so that they flew where they were safe from my companions catapult, and then I fled home. And ever since then, when the Passiontide bells ring out to the leafless trees and the sunshine, I reflect with a rush of grateful emotion how on that day their music drove deep into my heart the commandment: Thou shalt not kill.

From that day onward I took courage to emancipate myself from the fear of men, and whenever my inner convictions were at stake I let other peoples opinions weigh less with me than they had done previously. I tried also to unlearn my former dread of being laughed at by my school fellows. This early influence upon me of the commandment not to kill or to torture other creatures is the great experience of my childhood and youth. By the side of that all others are insignificant.

[ I ]

While I was still going to the village school we had a dog with a light brown coat, named Phylax. Like many others of his kind, he could not endure a uniform, and always went for the postman. I was, therefore, commissioned to keep him in order whenever the postman came, for he was inclined to bite, and had already been guilty of the crime of attacking a policeman. I therefore used to take a switch and drive him into a corner of the yard, and keep him there till the postman had gone. What a feeling of pride it gave me to stand, like a wild beast tamer, before him while he barked and showed his teeth, and to control him with blows of the switch whenever he tried to break out of the corner! But this feeling of pride did not last. When, later in the day, we sat side by side as friends, I blamed myself for having struck him; I knew that I could keep him back from the postman if I held him by his collar and stroked him. But when the fatal hour came round again I yielded once more to the pleasurable intoxication of being a wild beast tamer!

[ I ]

During the holidays I was allowed to act as driver for our next door neighbor. His chestnut horse was old and asthmatic, and was not allowed to trot much, but in my pride of drivership I let myself again and again be seduced into whipping him into a trot, even though I knew and felt that he was tired. The pride of sitting behind a trotting horse infatuated me, and the man let me go on in order not to spoil my pleasure. But what was the end of the pleasure? When we got home and I noticed during the unharnessing what I had not looked at in the same way when I was in the cart, viz., how the poor animals flanks were working, what good was it to me to look into his tired eyes and silently ask him to forgive me?

On another occasionit was while I was at the Gymnasium, and at home for the Christmas holidaysI was driving a sledge when a neighbor dog, which was known to be vicious, ran yelping out of the house and sprang at the horses head. I thought I was fully justified in trying to sting him up well with the whip, although it was evident that he only ran at the sledge in play. But my aim was too good; the lash caught him in the eye, and he rolled howling in the snow. His cries of pain haunted me; I could not get them out of my ears for weeks.

[ I ]

I have twice gone fishing with rod and line just because other boys asked me to, but this sport was soon made impossible for me by the treatment of the worms that were put on the hook for bait, and the wrenching of the mouths of the fishes that were caught. I gave it up, and even found courage enough to dissuade other boys from going.

Next page