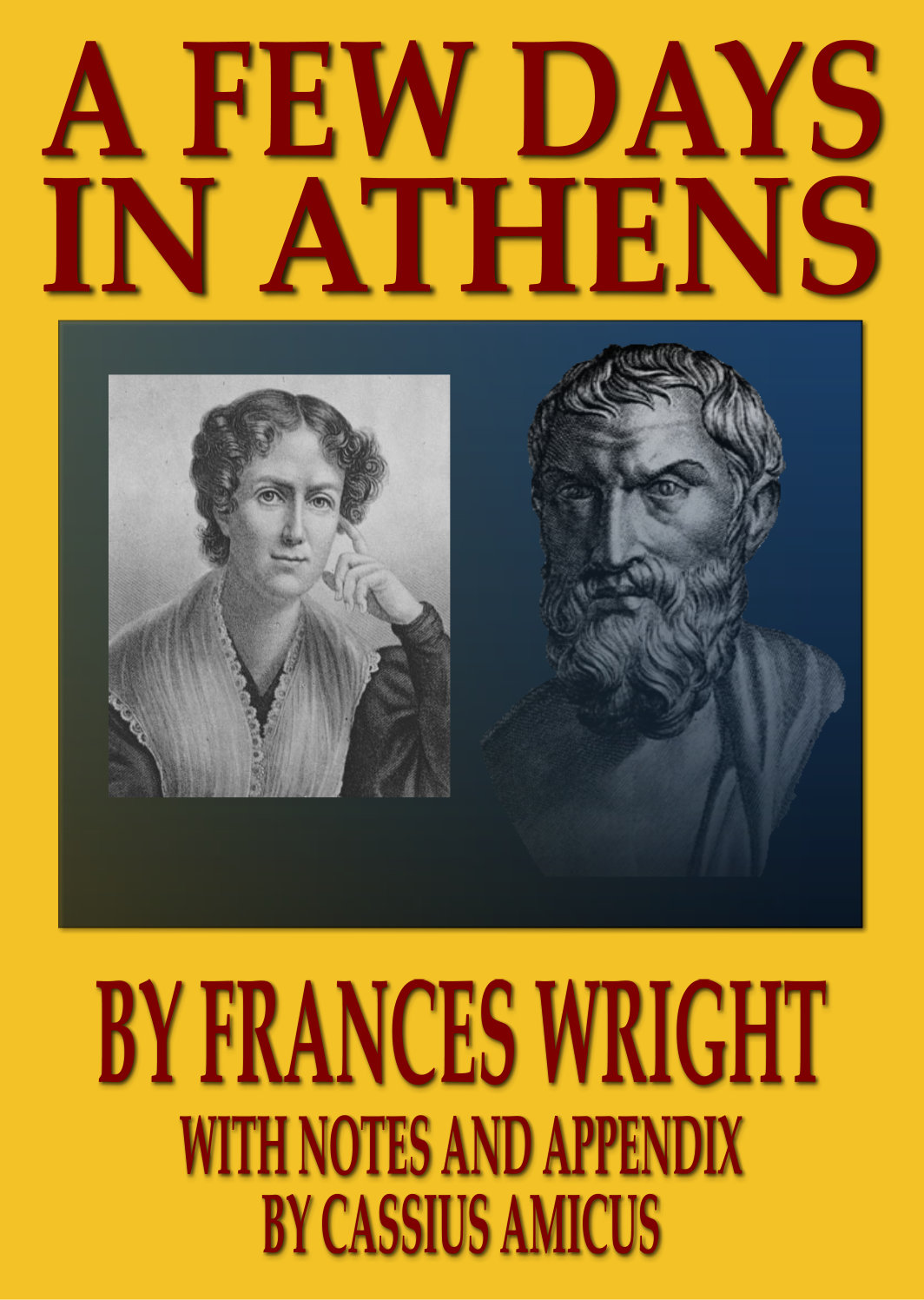

A FEW DAYS IN ATHENS

By Frances Wright

With Introduction, Additional Notes, and Appendix

By Cassius Amicus

2013

Published by Cassius Amicus.

Copyright 2013 Cassius Amicus

All Rights Reserved.

Smashwords Edition

ISBN: 9781301255252

No copyright or other rights are claimed

in the original text of

A Few Days In Athens

published by Frances Wright in 1822.

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION BY CASSIUS AMICUS

Frances Wright was born in Dundee, Scotland, on September 6, 1795, one of three children of a wealthy linen manufacturer. She became an orphan at age three, and was raised by an aunt in England. At age sixteen, she returned to Scotland to live with her great-uncle, a professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow.

In 1818, Wright traveled to the United States, where she published and produced a play on the subject of Switzerlands struggle for independence. After returning to Scotland in 1821, she published the work for which she became well known, a story about her travels entitled Views of Society and Manners in America .

In 1821, Wright published A Few Days in Athens , supposedly at the insistence of the Marquis de Lafayette, who later became her travel companion when she returned to America. Lafayette forwarded a copy of this work to Thomas Jefferson, who replied to him in 1823, with the following:

I thank you much for the two books you were so kind as to send me by Mr. Gallatin. Miss Wright had before favored me with the 1st edition of her American work: but her Few Days in Athens was entirely new, and has been a treat to me of the highest order. The matter and manner of the dialogue is strictly antient; the principles of the sects are beautifully and candidly explained and contrasted; and the scenery and portraiture of the Interlocutors are of higher finish than any thing in that line left us by the antients; and, like Ossian, if not antient, it is equal to the best morsels of antiquity. I auger, from this instance, that Herculaneum is likely to furnish better specimens of modern, than of antient genius; and may we not hope more from the same pen?

Wright gave A Few Days In Athens the subtitle Being the translation of a Greek manuscript discovered in Herculaneum , and she referred to herself in the introduction as translator. This was but a literary device, however, as the work was entirely modern.

A Few Days In Athens is composed in the style of an ancient dialogue by a Plato or a Lucian. As Thomas Jefferson stated, the story is beautifully and candidly explained, but the text is deep with allusions to the views of competing schools of philosophy. These allusions give the work much of its charm, but will be unfamiliar to many modern readers. It is therefore worth spending a few moments to review the general background and nature of the disputes between the major schools of philosophy disputes that continue little changed to this very day.

The setting of Wrights story is ancient Athens, and the main character is Theon, a young man from Corinth, whose father has sent him there for an education. Theons father favored the school of Plato, known as the Academy, but after arriving in Athens, Theons loyalty has been won by the school of Zeno, known as the Stoics, and also referred to by its nickname of the Porch or the Portico. Also mentioned are the school of Aristotle and Theophrastus, known as the Peripatetic or the Lyceum, and the schools of Pythagoras and of the Cynics. Each school has unique characteristics, but they are united in their common contempt for Epicurus, the son of Neocles, also referred to as the Gargettian, and whose school was known as the Garden.

A truly satisfactory review of the disputes between these schools is beyond the scope of this introduction, but readers should be aware that, in general, and to a greater or lesser degree, each of the non-Epicurean schools held the following:

- The universe was created by god(s) or forces which control all things, including the affairs of men, and men are fated to their peculiar destinies.

- Men have eternal souls and should expect a future life after death, including reward or punishment for acts committed during their lifetimes.

- Men should guide their lives by looking for a greatest good, which is generally to be found in some combination of virtue and the will of the gods.

- Men should look upon pleasure as unvirtuous, unreasonable, and sinful.

- Men should look upon pain as virtuous, instructive of the will of the gods, and something to be suffered without resistance or complaint.

- The senses, understood to be the abilities of seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, and tasting, are neither reliable nor sufficient for discovering truth or determining how men should live.

- Reason supplemented by revelation, where available, is the primary tool for discovering truth and determining how men should live.

Epicurus disputed each of the above points with vigor, but often with subtlety, in a way readers both ancient and modern find to be unfamiliar and challenging. For example, in regard to the existence of gods and fate, Epicurus did not simply deny that these existed. Instead, Epicurus determined that the rules of evidence that men were following were incorrect, and that the evidence in fact pointed in another direction. He concluded that words such as gods and fate and virtue need not be discarded, but should rather be cleansed of their inaccuracies, while the elements of truth that they held should be retained and described with greater accuracy. This process led him to the following conclusions:

- Neither gods nor fate exist in the way that these words are commonly defined. In regard to gods, the evidence establishes that the elements can neither be created nor destroyed, and therefore the universe as a whole is eternal, not created at any point in time by any supernatural god. But reliable evidence that is not pure speculation does exist to support the view that orders of life superior to our own exist elsewhere in the universe, and that among these are higher beings which have attained a state of immortal and self-sufficient blissfulness. These higher beings have a material existence, like all else that exists, but because they are self-sufficient they do not intervene in the lives of men. Gods play no role in determining the lives of men, but, under certain conditions, men may glimpse faint images of the higher state of blissfulness which the gods have attained. From these images, men can gain a sense of perfection that can serve as a model for what we should seek to attain in our own lives. In regard to fate, although purely mechanical laws do govern the operation of non-living matter, neither men nor gods are machines whose actions are pre-determined. Living beings have free will, and are not subject to mechanical laws or fate of any kind. As a result, men are responsible for using their free will to live without assistance from the gods.

- Men do indeed have souls, but that these souls are neither eternal nor supernatural. Instead, souls are composed of material that has a real existence, and they are as much a real part of this universe as anything else that exists. Whether the soul be referred to as consciousness, mind, or by some other term, the continuity of soul ends at death, after which there is no afterlife of reward or punishment. From the perspective of each man, the state of things after his death is the same as before his birth. We have no more reason to fear or regret our nonexistence after death than we fear or regret our state of nonexistence before birth. There is no reward in heaven to encourage our postponement of the enjoyment of life, nor an afterlife of punishment in hell to cause us fear. The focus of our existence must be on this lifetime, as we have but one life to live.

Next page