THE JOURNALS

OF

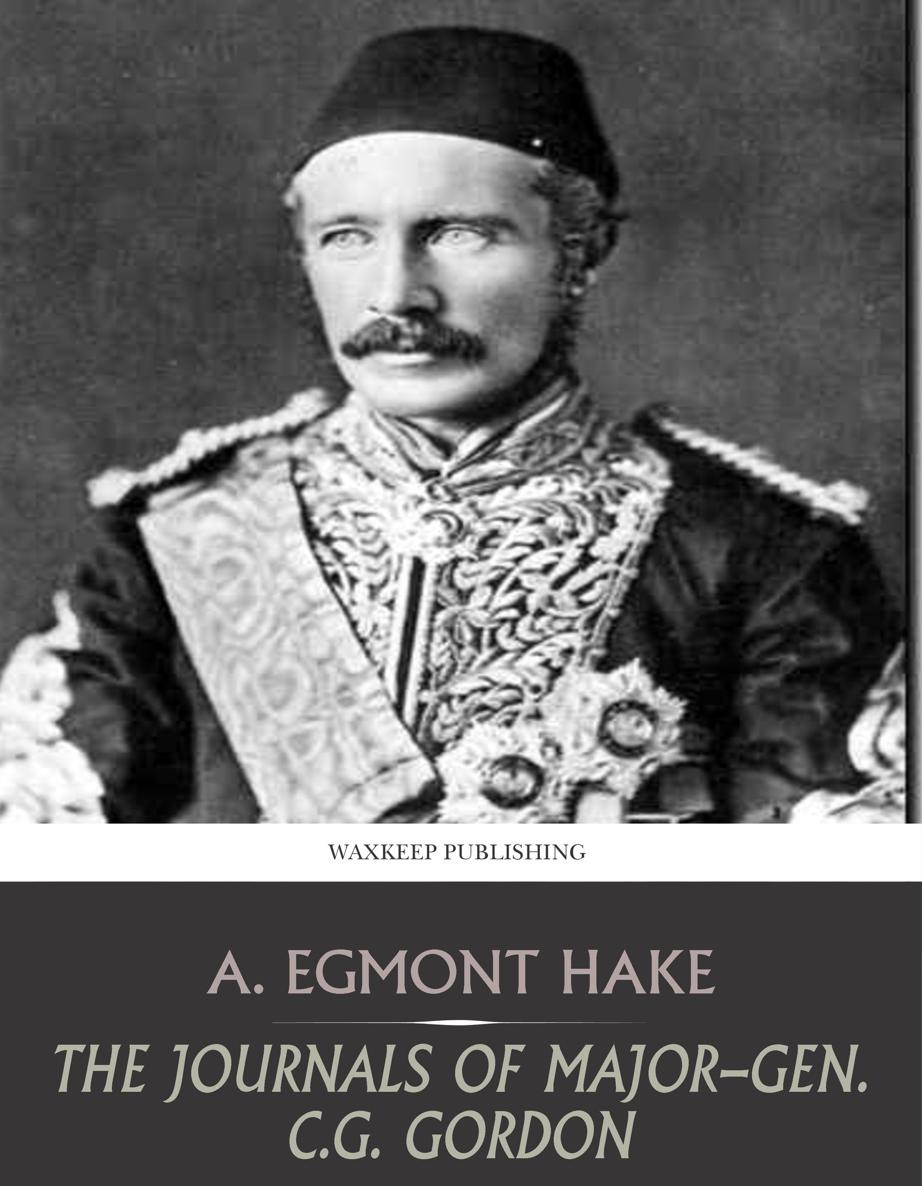

MAJOR-GEN. C. G. GORDON, C.B.,

AT KARTOUM.

THE JOURNALS

OF

MAJOR-GEN. C. G. GORDON, C.B.,

AT KARTOUM.

PRINTED FROM THE ORIGINAL MSS.

INTRODUCTION AND NOTES

BY

A. EGMONT HAKE,

AUTHOR OF THE STORY OF CHINESE GORDON, ETC.

WITH PORTRAIT, TWO MAPS, AND THIRTY ILLUSTRATIONS AFTER SKETCHES

BY GENERAL GORDON.

LONDON:

KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, & CO., 1 PATERNOSTER SQUARE.

1885.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, Limited.

STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING CROSS.

The rights of translation and of reproduction are reserved.

INTRODUCTION.

Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears;

I come to bury Csar, not to praise him.

The evil that men do lives after them;

The good is oft interred with their bones.

Good friends, sweet friends, let me not stir you up

To such a sudden flood of mutiny.

They that have done this deed are honourable;

What private griefs they had, alas! I know not,

That made them do it; they are wise and honourable,

And will no doubt, with reasons answer you.

But were I Brutus,

And Brutus Antony, there were an Antony

Would ruffle up your spirits, and put a tongue

In every wound of Csar, that should move

The stones of Rome to rise and mutiny.

These grand lines force themselves upon me, though maybe their analogy is incomplete. Mark Antony was a casuist, and pleaded the cause of revenge; I am only earnest in the cause of justice. Yet I trust in my pleading to enable Englishmen to realise how great and how sad is the loss of Charles Gordon, not only to those who loved him, but to the cause of suffering humanity. Gordon is dead. We cannot bring him back to life. Yet from his death we may learn at least how fit he was to teach us while he lived, how fit to hold his countrys honour in his hand, how fit to judge of what was right and what was wrong. His journals are his last words to the world as much as they are instruction and information to his Government, and Englishmen who value Englands honour may well read them with a heavy heartwith eyes dimmed by tears. I say Gordon is dead, and we cannot bring him back to life, but we can do much he would have done for us had he been allowed to live. His journals tell us how we can best repair mischief already done (and I understand his words to apply rather to the English people than to the Government which represents them), and they tell us what is best for the Soudan. In the interest of this unhappy land he devoted much of his life; in its interest he died. Let us then compare the opposite conditions under which the people existed during Gordons presence and absence, and in doing this let us mark well what Gordon said during his life, and what his journals say for him now that he is dead.

Gordon used to tell the story of how, when Said Pasha, Viceroy of Egypt before Ismail, went up to the Soudan, so discouraged and horrified was he at the misery of the people, that at Berber he threw his guns into the river, declaring he would be no party to such oppression. In this spirit Gordon went there as Governor of the Equator in 1874, and in this spirit he expressed his views on the duties of foreigners in the service of Oriental States. His ardent and unstudied words are worthy of the deepest study. They breathe the kindliest wisdom, the most prudent philanthropy; and it would be well if those whose lot is thrown in barbarous lands would take them for a constant guide. To accept government, only if by so doing you benefit the race you rule; to lead, not drive the people to a higher civilisation; to establish only such reforms as represent the spontaneous desire of the mass; to abandon relations with your native land; to resist other governments, and keep intact the sovereignty of the State whose bread you eat; to represent the native when advising Ameer, Sultan or Khedive, on any question which your own or any foreign government may wish solved; and in this to have for prop and guide that which is universally right throughout the world, that which is best for the people of the State you serve.