THE WARRIOR IMAGE

2008 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Scala and Campaign types

by BW&A Books, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Huebner, Andrew J.

The warrior image : soldiers in American culture from the Second

World War to the Vietnam era / by Andrew J. Huebner.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8078-3144-1 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8078-5838-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. United StatesHistory, Military20th century. 2. United

StatesHistory, Military20th centuryPictorial works. 3. Soldiers

United StatesHistory20th century. 4. SoldiersUnited States

History20th centuryPictoral works. 5. Soldiers in art.

6. Soldiers in literature. 7. Soldiers in motion pictures. 8. United

StatesCivilization1945 9. United StatesCivilization1945

Pictorial works. 10. Popular cultureUnited StatesHistory

20th century. i. Title.

E745.H84 2008

306.27097309045 dc22 2007027989

A version of chapter 4 appeared as Kilroy Is Back: Images of American Soldiers in Korea, 195053, American Studies 45, no. 1 (Spring 2004): 10329. 2004 by the Mid-America American Studies Association. Used by permission. A version of chapter 6 appeared as Rethinking American Press Coverage of the Vietnam War, 196568, Journalism History 31, no. 3 (Fall 2005): 15061. 2005 by the E. W. Scripps School of Journalism, Ohio University. Used by permission. Acknowledgments of permission to reprint other copyrighted material appear in a section preceding the index.

12 11 10 09 08 5 4 3 2 1

In memory of

Doris Hultgren Huebner

and John L. Thomas

And for Mom, Dad, and Min

War is not nice. War is something else.

WILLIAM EASTLAKE, The Bamboo Bed (1969)

CONTENTS

FIGURES

1 Jean Moore kneels and kisses her fianc, Ralph Neppel, 1945

2 Tom Lea, The Price, 1945

3 Burned and bandaged men aboard the USS Solace, 1945

4 Tom Lea, That 2,000-Yard Stare, 1945

5 Bill Mauldin, Fresh, spirited American troops... , 1945

6 The Negro Seabees training near Norfolk, Virginia, ca. 1942

7 Begrimed and weary marines at Eniwetok Atoll, 1944

8 Pfc. Orvin L. Morris rests during evacuation to Pusan, Korea, 1950

9 Grief-stricken American infantryman, 1950

10 General MacArthur inspects the Twenty-fourth Infantry, 1951

11 Integrated machine-gun unit north of the Chongchon River, 1950

12 Cpl. Leonard Hayworth breaks into tears, 1950

13 Capt. Ike Fenton learns he is out of ammunition, 1950

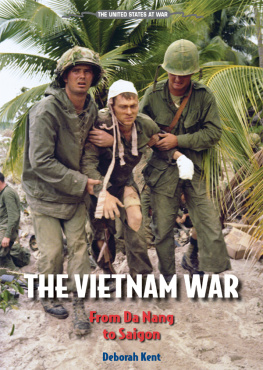

14 Whos Fighting in Vietnam, 1965

15 Invasion DMZ Runs into the Marines, 1966

16 Rising Doubt About the War, 1967

17 American marines at Hu City during the Tet offensive, 1968

18 Bill Henshaw, disabled Vietnam veteran, 1973

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In the course of writing The Warrior Image I benefited from the accessibility, kindness, and support of several mentors. First and foremost, I was fortunate to have James Patterson as my thesis adviser at Brown University. From the beginning, Jim was the model of a superior teacher, scholar, and friend. His careful editing, probing questions, and moral support have made this book immeasurably better, and I thank him as well for his continuing guidance and generosity. Howard Chudacoff, Karl Jacoby, and Elliott Gorn were all extraordinarily gracious and encouraging readers, and this book was much improved by their unique contributions. Tom Gleason was also extremely supportive and helpful in myriad ways. And I cannot overstate the influence of the late Jack Thomas, who not only read the manuscript and improved it with his insights, but was also a dear friend throughout my years in graduate school. Had Jack lived to see this book come out, Im sure it would have joined the works by his former students that he proudly stacked up in his living room.

I am deeply grateful to John Bodnar and Marilyn Young for their perceptive critiques of the manuscript in its draft stagesboth of them were especially helpful in challenging me to clarify the books aims and arguments. For similarly helping to sharpen my thinking I am indebted to John Baky, William Chafe, Edward M. Coffman, Zac Coile, Nancy Huebner, Mike Majoros, Kurt Piehler, Woody Register, Rob Riser, Jim Sparrow, Travis and Kristin Stolz, and Josh Zeitz. Several colleagues, friends, and relatives read some or all of the chapters: Jan Brunson, Robert Fleegler, William Gillis, Morgan Grefe, Jim Huebner, John Huebner, Wendy Huebner, Brendan Schriber, and Paul White. As the project took shape Robert, Morgan, and Jan offered me constant encouragement, curiosity, and intellectual energy, and later in the process Paul was similarly generous with his time and ideas. At UNC Press Chuck Grench, Paul Betz, Katy OBrien, and Liz Gray have been genial and supportive throughout the publishing process.

I could not have completed the research for this book without the help of staff members at the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, the National Archives in Maryland and Washington, the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison, the Museum of Modern Art Archives in New York, the La Salle University Library in Philadelphia, and the John Hay Library in Providence.

For help tracking down and securing permissions for poems, I owe a debt of gratitude to Jan Barry, W. D. Ehrhart, Robert Hedin, Larry Rottmann, William Childress, Rolando Hinojosa, Stan Platke, Earl E. Martin, Charles Purcell, Margaret Nemerov, Maureen Sylak, and Ruth Wantling. Merrily Harris and Jessica Lacher-Feldman generously provided much-needed assistance with acquiring image permissions. At the University of Alabama, the William G. Anderson Endowed Support Fund helped offset the costs of those permissions. Two graduate students in Tuscaloosa, John Mitcham and Charles Roberts, graciously aided me in the process of proofreading. And I thank David Douglas Duncan for speaking with me about the project and granting permission to reproduce his haunting photographs.

Looking further back into my own past, it is evident that I never would have become a professional historian without the early encouragement of Jim Huebner, Lee Huebner, and Mike Naylor. And for all their love and support, my deepest thanks go to the best people I knowMom, Dad, and my brother Min.

THE WARRIOR IMAGE

INTRODUCTION: BEYOND TELLING OR IMAGINING

Reflecting on more than two decades of experience covering conflict, the eminent war correspondent Martha Gellhorn wrote in 1959, War is a malignant disease, an idiocy, a prison, and the pain it causes is beyond telling or imagining; but war was our condition and our history, the place we had to live in.

This merging of military history and cultural historyone something of a pariah in the American academy, the other the heir apparent to the new social history emerging from the 1960sis particularly suited to studying America in the years beginning with World War II.cultural representations of soldiers, forming the architecture of what I call the warrior image from the 1940s to the late 1970s.

Of course the warrior image has had a long and varied history. From ancient times to the twenty-first century, and in all the worlds cultures, people have felt the need to make sense of, glorify, or lament this most disturbing of human practiceswar is, after all, the place we had to live in, according to Gellhorn. In the many centuries before World War II, artists and writers depicted and remarked upon the nature of warfare through the principal cultural forms of the day: stories, drawings, paintings, murals, tapestries, poems, sculptures, memorials, and songs. Throughout history people have created images of soldiers ranging from the heroic to the pitiful, and in doing so have said much about their own societies. A brief survey of this immense body of cultural output helps frame the issues of emphasis in my own study of modern American war imagery.