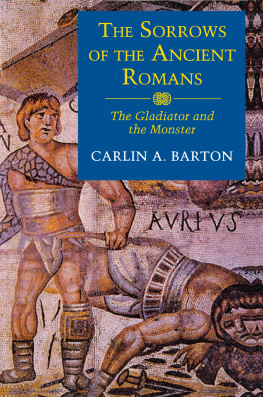

COPYRIGHT 1993 BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PUBLISHED BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 41 WILLIAM STREET,

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 08540

IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, CHICHESTER, WEST SUSSEX

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

BARTON, CARLIN A., 1948-

THE SORROWS OF THE ANCIENT ROMANS : THE GLADIATOR AND

THE MONSTER /

CARLIN A. BARTON.

P. CM.

INCLUDES INDEX.

ISBN 0-691-05696-X

ISBN 0-691-01091-9 (PBK.)

eISBN: 978-0-691-21967-7

1. NATIONAL CHARACTERISTICS, ROMAN. I. TITLE.

DG78.B37 1992 937DC20 92-13603

R0

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I WISH TO THANK the following individuals for reading and criticizing the whole or parts of the manuscript: John Bodel, Peter Brown, Miriam Chrisman, Mark Cioc, Jean Elshtain, Erich Gruen, Thomas Habinek, William Johnston, Ray Keifetz, Elizabeth Keitel, Barbara Kellum, Amy Richlin, Charles Rearick, Nathan Rosenstein, Carole Straw, Richard Trexler, Valerie Warrior, and Patricia Wright. Their help has been deeply appreciated. I would also like to thank the participants of the Five College Social History Group (Smith College, 1986), the New England Ancient History Colloquium (Mount Holyoke College, March 1987), and the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Massachusetts (Fall 1988) for their valuable contributions to the development of my ideas.

I would like to thank the University of California Press for permission to reprint The Scandal of the Arena, which appeared in Representations 27 (Summer 1989), and the superintendent of archaeology of the city of Naples for permission to reprint the photograph of the gladiator tintinnabulum.

THE SORROWS OF THE ANCIENT ROMANSINTRODUCTION

T HIS IS A BOOK about the emotional life of the ancient Romans. In particular, it is about the extremes of despair, desire, fascination, and envy, and the ways in which these emotions organized the world and directed the actions of the ancient Romans.

This is a book about the gladiator and the monster, the most conspicuous of the figures through which these extremes of emotions were enacted and expressed.

This is a book about paradox and reciprocity, about boundaries, transgressions, and expiations.

This is a book, finally, about homo in extremis, the human being and human society at and beyond the limits of endurance.

I have written in an effort to address some of the darkest riddles of the Roman psyche, because I suspected that they were some of the riddles of my own life and perhaps of human life: the conjunctions of cruelty and tenderness, exaltation and degradation, asceticism and license, erethism and apathy, energy and ennui, as they were realized in a particular historical and sociological setting, the period of the civil wars and the establishment of the monarchy, roughly the first century B.C.E. and the first two centuries C.E.

The purpose of the work has not been to produce a set of conclusions, but rather a map of what one reader has called the uncharted regions of Roman life: those areas of Roman collective psychology that have heretofore largely resisted interpretation on account of the dispersed, contradictory, and troubling sources, and the even more troubling subject matter. I have tried to construct a physics of emotions that suffused Roman action without producing in that culture a systematic exegesis, of patterns that so saturated the life of this period that they are difficult to distinguish from consciousness itself, of paradoxes that constituted a kind of white noise in Roman culturepervasive, yet resisting articulation, and so complex as to verge on silence.

This is a work of popularization; I am hoping to attract an audience beyond that of my own discipline of Roman history. But it is by no means intended as a work of simplification. On the contrary, I have tried to present the most complex understanding of which I am capable, the most complex understanding that I can enunciate. My goals have been to organize and clarify, without unduly rectifying, the masses of entangled and disconnected material in a way that would be agreeable to the generally educated reader and acceptable to the specialist in Roman history. To achieve the first goal, I have welcomed the guidance of modern theorists: psychologists, anthropologists and sociologists. To achieve the second, I have relied on the patient and careful labors of countless other ancient historians.

My methods may not appear excessively strange to ethnologists and historians of mental life, but they may cause some consternation to ancient historians. I wish, therefore, to anticipate the reactions of some of my readers and address briefly some issues of concern to ancient historians.

There are many types of sources that ancient historians are trained to dismiss or be wary of: literature and professed fictions in general (especially literary topoi), rhetoric (especially philosophical), and banalities and commonplaces of all sorts. They are the veils or scrims obscuring a reality whose authentic categories are politics, economics, and law (or class, gender, and age). But for my purposes, the truth, sincerity, or authenticity of the ancient statements or stories that I repeat is largely irrelevant. I am concerned with mapping Roman ways of ordering and categorizing their world, and of transgressing, denying, or obliterating those orders. What made things seem real or unreal to a Roman at a particular moment is of greater concern to me than what was (or is) real. As possible clues to the physics of the emotional world of the Romans, the metaphor, the fantasy, the deliberate falsehood, the mundane and oft-repeated truism, the literary topos, the bizarre world of schoolboy declamations, and the cultural baggage taken over from the Greeks are as valuable as a report of Tacitus or an imperial decree. For my purposes, all of the sources are equally true and equally fictive.

Some readers may feel that I have cast my net altogether too widely through the sources. While the center of my field of vision has been the early Empire, particularly the age of Nero (because it is the period I understand best, the one in which the sources are most familiar and the patterns are clearest), the circle of my attention embraces the last century of the Republic and the first two centuries of the Empire, years in which 1 believe I can see certain patterns emerging and developing. But my peripheral vision often exceeds these limitations in the search for any idea or experiencealways privileging the Romanthat can help me illuminate the material on which I am focused. In attempting to catch phenomena which suffused the society of ancient Rome in a particular period, but of which there exist few connected analyses in the sources, I have often stretched my time frame past its stated limits or filled in the Roman puzzle with bits and pieces of other far-flung cultures, including my own.