All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

PROLOGUE

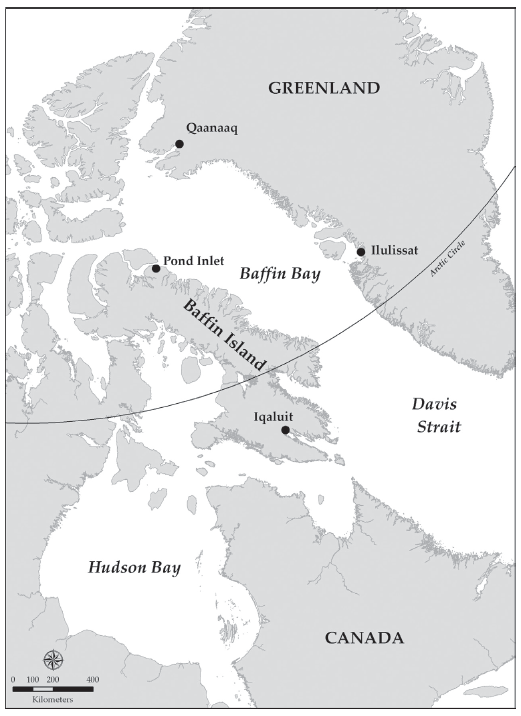

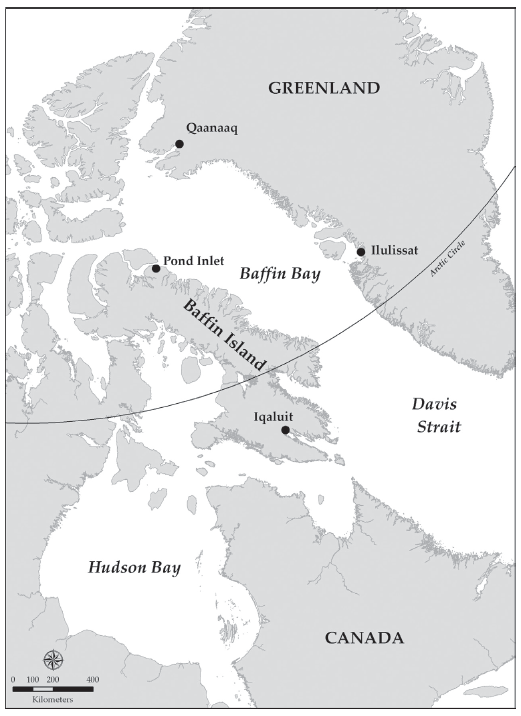

THE INUIT LEGEND OF THE ORIGIN OF THE NARWHAL HAS BEEN told in many versions throughout the eastern Canadian Arctic, with some being quite long and detailed and others simple and unadorned. Although the basic story is similar, each person brings to the tale slight variations reflecting the individuality of the oral tradition. This version was told to narwhal researcher Martin Nweeia by Elisapee Ootuva, an elder from Baffin Island and the author of the first Inuit-to-English dictionary. In Alaska and the western Canadian Arctic, outside the native range of the narwhal, the story is sometimes called The Blind Boy and the Loon, and the ending refers to walruses or polar bears.

A wicked woman lived with her daughter and her son, who was born blind. As the son got older, his sight improved, even though the mother tried to convince him of his helpless state. One day a polar bear came near the house and the mother told the son to aim a bow and arrow at the bear through the window covered with seal skin and strike him down. The boy pulled back the arrow and the mother took aim for him. The arrow struck the heart of the bear and although the boy could hear the groans of the dying bear, the mother laughed scornfully at him, saying that he had missed the bear. That night the mother and the daughter had fresh polar bear meat while the mother cooked dog meat for the son. Later the boy's sister told her brother that his shot was successful and secretly gave him some of the polar bear meat.

Time passed and an old man came to the house for a visit. Before he left, he told the young girl how she could help her brother regain his sight. In the spring, he told them to watch for a red-throated loon who would swim trustingly toward them. Once the loon was close enough, the blind brother should wrap his arms around the loon's neck and theloon would take him to the bottom of the lake. Once they came up, his sight would return. The loon told the young man not to tell about his regained sight until later in the summer when he would send a pod of belugas to their campsite.

When summer came and the ice began to break, the belugas began to move. On one occasion, a pod was closer to land than usual. The young man grabbed his harpoon and told his sister to accompany him to help him aim. They went to the shoreline and the mother, seeing the son with a harpoon, became concerned and followed them. Once she was close to them, the son gave the end of the line from the harpoon to his mother, asking her to tie it around her waist to hold the harpooned animal. The concerned mother told her daughter to make sure he was after a small animal as she was tied to the harpoon. The son instead aimed for the largest whale and harpooned him. The mother was cast into the sea. As she submerged she spiraled around the line, with her long hair twisting into a long lance. This is how the narwhal came to be.

ONE

FIRST ENCOUNTER

I THINK I WAS NINE WHEN I FIRST BECAME ENAMORED OF THE narwhal, the mysterious sea creature that most people, even today, aren't sure is actually real. Their confusion arises from the whale's connection to the mythical unicorn, whose horn, modeled after the narwhal's tusk, was reputed to have healing properties. But I knew back then that narwhals were real. And I knew that the truth about the ice whale was even better than the myth with which it had become entangled.

When I stumbled across the narwhal in the pages of the World Book Encyclopedia, I was struck by the odd combination of tusk and ice and whale, making the narwhal far more intriguing than the local frogs and turtles this Rhode Island grade-schooler sought out every day. When I discovered a long spiral tusk in a Vancouver curio shop two decades laterlabeled with a price tag of $10,000my interest was rekindled, though I assumed I would never actually see one alive in the wild. Reports of the threats narwhals face from the melting of their icy world, along with conflicting and inaccurate information online and in other venues, prompted me to undertake a series of journeys far above the Arctic Circle to find the truth and reveal the narwhal's unique life cycle and remarkable physical feats.

Narwhals have been surrounded by mystery, mythology, and awe for centuries. They've been celebrated as sea unicorns, held up as proof of the existence of a land-based unicorn, and cherished for their high-quality oils. They've been a vital source of meat in the diet of Arctic natives and important to them as a cultural icon. Today they are surrounded, as well, by great concern for the potential harm that could come to them from retreating sea ice, increased shipping and oil exploration, and changes in environmental conditions caused by a warmingplanet. For a mammal that is so uniquely adapted to thriving in the numbing waters of the Arctic, warming is a significant threat, especially at the rate that it is taking place today.

Yet it is the narwhal's tusk that is clearly its most distinctive feature: it is the most remarkable tooth in nature, and the trait that has generated the most interest and attention since the earliest days of its discovery. It's the source of its taxonomic name, Monodon monoceros, meaning one tooth, one horn, but its common name comes from its grayish coloration. The Old Norse prefix Nar means corpse, and hval means whale, so the narwhal is the corpse whale, because its skin color makes it resemble a floating corpse. Despite the origin of its name, Nobel Prize-winning Chilean poet Pablo Neruda wrote that narwhal is the most beautiful of undersea names, the name of a sea goblet that sings, the name of a crystal spur.

To me, however, it is not just the narwhal's name and tusk that make it distinctive and notable. For narwhals live in a world few can even imagine, where darkness and icy conditions are insurmountable barriers to all but a few predators, some of which may venture north during the warmest months to partake of the region's food-rich waters but then quickly depart for warmer climes at the onset of fall like so many human snowbirds. Their food source is often found more than a mile deep, where few mammals can survive. It's the physiological adaptations to cold and deep divingand to darkness, too, forcing them to rely much more on their hearing and acoustics than on sightthat put the narwhal on the top of my list of most revered animals.