Contents

Guide

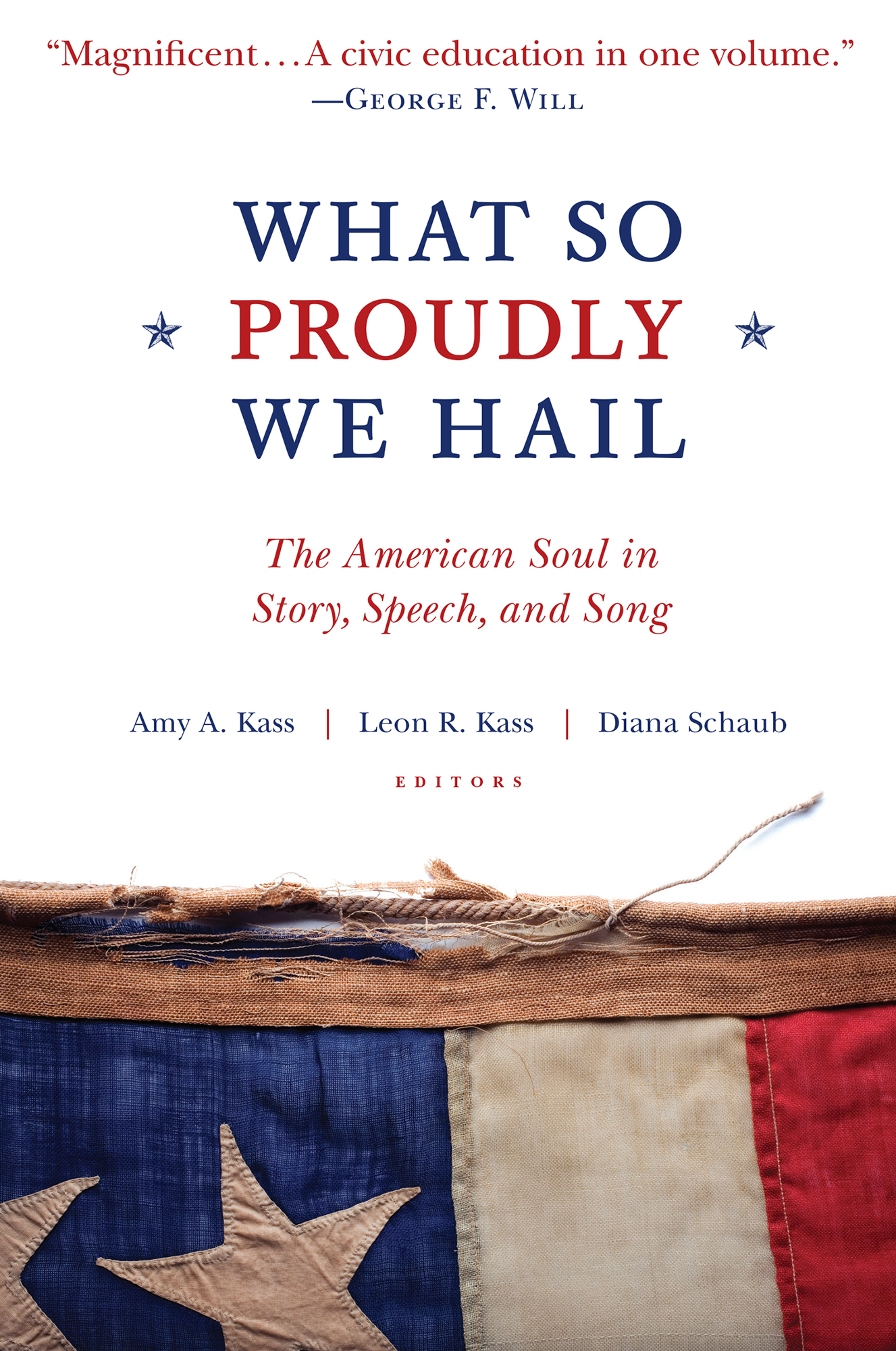

Magnigicent A civic edication in one volume. George F. Will

What So Proudly We Hail

The American Soul in Story, Speech, and Song

Amy A. Kass

Leon R. Kass

Diana Schaub

Editors

To Our Students

For additional materials and opportunities for comment, readers are invited to visit our website: www.whatsoproudlywehail.org

Introduction

T his is a book about America for every American. More precisely, this is a book about American identity, American character, and American citizenship. Addressing hearts as well as minds, exploiting the soul-shaping powers of story, speech, and song, it is designed to make Americans more appreciatively aware of who they are as citizens of the United States. Its ultimate goal, stated without apology, is to produce better patriots and better citizens: men and women knowingly and thoughtfully attached to our country, devoted to its ideals, and eager to live an active civic life.

Although we are committed to the goal of producing thoughtful patriots and engaged citizens, the editors have no partisan political agenda or ideological intentions. The patriotism we seek to encourage is deep, not superficial; reflective, not reflexive; and, above all, thoughtful. This anthology addresses liberals and conservatives, Democrats and Republicans and independents, employers and employees, rich and poor, young and old, and Americans of every race, religion, and ethnicity, for all Americans have a stake in the well-being of our nation.

Thoughtful Americans have a stake as well in the questions explored in this book: Who are we? How do we identify ourselves, as individuals and as a people? What do we look up to and revere? To what larger community and ideals are we attached and devoted? For what are we willing to fight and to sacrifice? How can America produce citizens who are knowledgeably attached to their country and their communities, and who possess the characterthe attitudes, sensibilities, and virtuesnecessary for robust civic engagement? How do weparents, teachers, and community leadersform good citizens?

Challenges for American Identity and Citizenship, New and Old

These enduring questions are again timely, indeed urgent, as current circumstances present new reasons to be concerned about Americas future. Numerous studies have documented the cultural and historical illiteracy of todays youth, even among graduates of our best colleges. Knowledge of American history and government has declined, in part because these subjects are no longer centerpieces of public education. Very few colleges require students to take even a single course in matters American. Studies show that, despite volunteering more for community service, todays young people, compared with those of generations past, are less interested in public affairs, less likely to vote regularly, and less likely to stay informed about politics and current events. The reigning ideology that welcomes immigrants to our shores no longer calls for their assimilation into our melting pot but instead celebrates their diversity, multiplicity, and cultural distinctiveness; the political unum of America is lost amid the focus on the multicultural pluribus. Ironically, although recent immigrants (and their children) usually know from fresh experience how their lives have improved by coming to the United States, the well-off children of the native-born, knowing little of history or of current political alternatives around the globe, take for granted the privileges of American citizenship and prosperity. Increasingly, leading intellectuals, opinion leaders, and politicians talk of globalization and the need to regard ourselves as citizens of the world. Between such cosmopolitan universalism and ethnic and racial tribalism, national pride and attachment are often disparaged, and in some quarters regarded as obsolete.

But national identity and citizenship in America face deeper and more permanent challenges, some linked to the special character of our liberal democratic republic. Citizenship in the United States is legally defined, by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, in this minimalist way: A citizen is any person born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof. The Constitution speaks of our rights as citizens; it never mentions any of our duties or what it takes to defend those rights. To be sure, becoming a citizen by naturalization requires passing certain tests, again rather minimal. For most Americans, however, citizenship is in no way earned; it is bestowed by the mere accident of birth within our borders.

Yet the American Republic was founded asand remainsa nation not of birth, lineage, or inherited ways but of ideas. It was the first nation to define itself in terms of certain teachings and aspirations, what may be thought of as the American creedthe equal rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; freedom of religion and religious toleration; majority rule; minority rights; and the rule of law. To exaggerate but slightly, anyone who embraces these universal ideas can become in spirit an American.

But for this reason, attachment to the United States cannot easily rely on patriotic emotions arising from familial, tribal, and religious ties or from traditional bonds to place, language, music, and inherited cultural norms. America, according to a patriotic song, may be the land where our fathers died, but we never refer to it as the fatherland (patria) or motherland, as do Germans or Russians regarding their native land. What takes the place of such deep sentimental attachments? Is acceptance of certain basic political or philosophical principles enough to make citizens willing to serve and sacrifice for their country in time of need?

Complicating the difficulty is the fact that America embraces people from all over the world, who come with different ways, speak different languages, and practice different religions. We have never had an established national church or even an articulated national morality. Our tolerance, and even encouragement, of ethnic and religious pluralism is a great national strength, but it also poses a challenge for creating a deep national bond and spirit. As a result, our emotional ties to our separate ways and beliefs often exceed ties to our common national whole. Our identification as Americans seems at best to be hyphenated, not unqualified.

National attachments may be harder to sustain also because America celebrates the individual, not the collective. The state, according to our creed, exists to protect the rights of individuals; the individual does not exist to promote the power or glory of the state. Our individual rights encourage our private pursuit of happiness and prosperitywithin the limits set by law, but not necessarily with a view to what would promote the common or public good. We jealously guard our freedoms and our privacy; save in times of national emergency, we are deeply suspicious of encroachments upon them, especially by the state. Making public-spirited citizens out of a nation of individualists has long been a challenge.

Americas embrace of science, technology, and other forms of progress paradoxically poses another challenge. The United States Constitution, silent on the all-important matter of educating citizens, speaks up in favor of progress in science and the useful arts: the first and only right mentioned in the original Constitution of 1787 is the right of authors and inventors to their writings and discoveries. But a people that looks largely to the future and that loves and rewards novelty is less likely to have reverence for the past or to care about preserving our institutions and mores. Our spectacular energy and enterprise and our penchant for innovation and improvementtraits made possible by the freedoms guaranteed under our Constitutionrender tenuous our sentimental attachments to the gifts and traditions that we have inherited. This long-standing difficulty becomes more severe in the age of cyberspace and instant communication.