The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2017 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-51854-1 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-51868-8 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-51871-8 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226518718.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jones, Graham M., author.

Title: Magics reason : an anthropology of analogy / Graham M. Jones.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2017. |Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017015013 | ISBN 9780226518541 (cloth : alk. paper) |ISBN 9780226518688 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226518718 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: MagicSocial aspects.

Classification: LCC BF1621 .J66 2017 | DDC 306.4dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017015013

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Dangerous Doubles

).

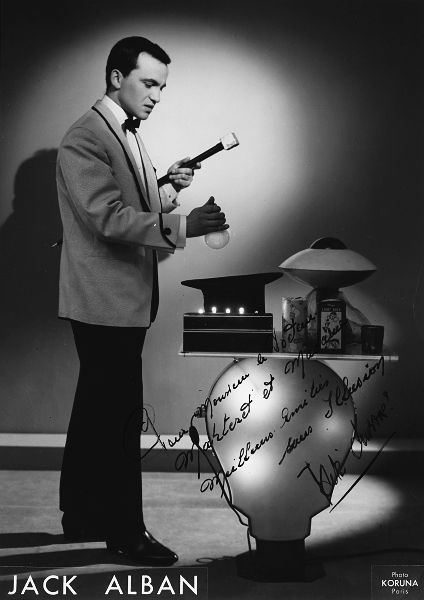

Figure 1. Illusionist Jack Alban, 1950s. Collection of Didier Morax.

In 1982 he became president of Frances National Illusionists Union (Syndicat National des Illusionnistes), which helps magicos file suit against employers who cheat them out of benefits. It sounded like frustrating work. Jack told me that his fellow magicians often didnt know anything about Frances byzantine employment regulations, and came to him years after the fact when they realized that they werent receiving retirement benefits they assumed they had coming. As part of my anthropological fieldwork on the subculture of magicos, I was hoping he could help me understand how the professional prospects for French magicians had evolved over the six tumultuous decades leading up to our meeting in 2004.

Given his serious position, I was surprised to find Jack homey, jovial, boisterous, and irreverent. He also happened to be bald, a feature I probably wouldnt have thought significant if he hadnt called it to my attention. You might not recognize me next time we meet, because I usually have a wig, he chortled. When its windy, I dont bother anymore. If it blows away, Im too old to chase it! It sounded like he was delivering a punch line, and we both laughed, but I later found out it was true.

Jack always jokingly referred to me as le Chinois, because when I cold-called him to introduce myself as an anthropologist studying magicto avoid confusion, I used the French word prestidigitation, which specifically denotes entertaining sleight of handhe thought I sounded Chinese. One of Jacks friends, Alain, a lanky, bespectacled Afro-Antillean computer engineer, joined us at the caf. He and Jack met at least once a month to swap the latest issues of magic magazines and dissect the secrets they contained. Alain kept an engineers meticulous ledger of each exchange in a computational notebook. When Jack found out I was of African American descent, he said he was tickled to be the milk with two coffees, even if one of them was Chinese.

At one point Jack reached into his satchel and presented me with a handwritten sheet of paper. A magician friend of mine knows something about anthropology, so I asked him to write down some things you could use for your research.

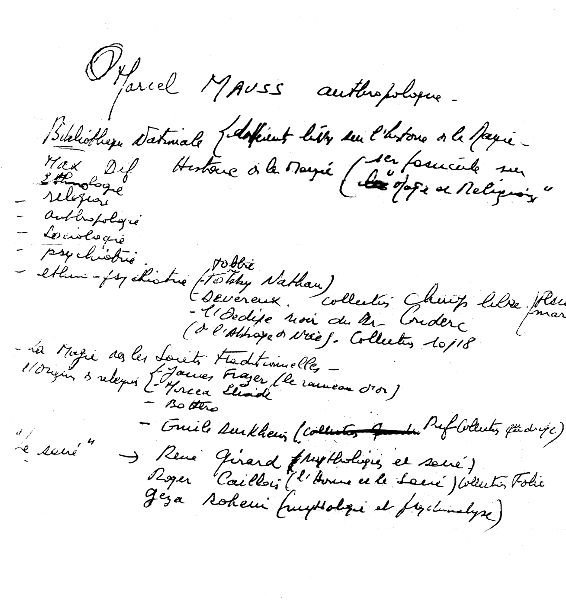

It was a bibliography ().

Figure 2. An illusionists bibliography on the anthropology of magic.

At the top of the page, the bibliographer had drawn a large bullet point, and had written next to it in large letters, Marcel MAUSS anthropologist. This was clearly a reference to the coauthor of the classic Outline of a General Theory of Magic, in which Henri Hubert and Mauss (19021903) boldly proposed that supernatural magical rites like casting spells or using charms could be explained strictly in terms of social relationships. Scanning the rest of the page, I recognized other similarly influential names. Under the heading Magic in Traditional Societies, the bibliographer had listed James Frazers Golden Bough (1900), an encyclopedic Victorian work of comparative mythology that locates the origins of religion and even science in ancient magical beliefs. Under the same heading, the bibliographer included Mausss uncle, mile Durkheim, whose Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1912) famously distinguishes religion, which constitutes a lasting community in the form of church, from magic, which has no institutions that transcend fleeting encounters between magicians and their clients.

Whoever had written this bibliography indeed knew more than just something about anthropology! He appeared to be widely conversant in the field. But perhaps there had been some misunderstanding, for he had included only references concerning occult magic and its relationship with ritual and religionworks peopled with sorcerers, shamans, witches, wizards, alchemists, and astrologers. These texts constituted the cornerstone of what I will henceforth refer to as anthropological magic theory, a speculative and empirical tradition devoted to explaining the prevalence and persistence of occult beliefs and practicesa tradition that is, along with the study of topics like kinship and ritual, an intellectual centerpiece of anthropology as a discipline.

I knew all too well that, with a few isolated exceptions, the scholars working in this tradition mostly treated the ludic, rabbit-in-a-hat, lady-in-a-box kind of magic that interested me as superfluous if not altogether irrelevant to their core concerns, scarcely referring to it at all. As Tanya Luhrmann (1997: 299), neatly summing up the logic of this exclusion, writes, the deliberate attempt to fool an audience that knows that it is being fooled just does not involve the same kind of intellectual problems as the study of magic as instrumental action. The bibliography included only one item manifestly pertinent to illusionism, magician and magic historian Max Difs (1986) standard French reference work Histoire illustre de la prestidigitation. Even here, the bibliographer specified that I should look at the first section on Magic and Religion, which covers materials similar to those addressed by Mauss, Frazer, and Durkheim: magical rites and shamanistic practices in prehistoric and ancient societies. Surely I wasnt studying

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).