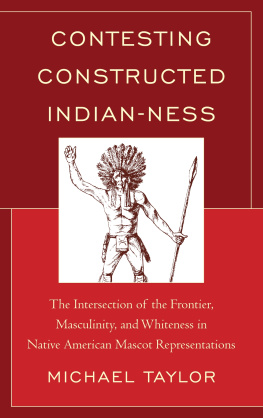

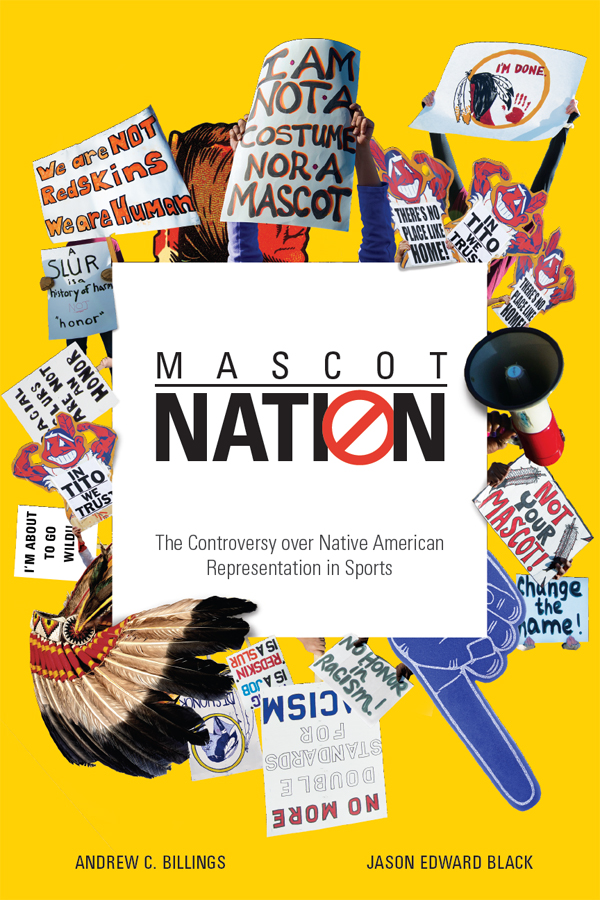

MASCOT NATION

The Controversy over Native American Representations in Sports

ANDREW C. BILLINGS AND

JASON EDWARD BLACK

2018 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Billings, Andrew C., author. | Black, Jason Edward, author.

Title: Mascot nation : the controversy over Native American representations in sports / Andrew C. Billings and Jason Edward Black.

Description: Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018020260| ISBN 9780252042096 (hardback : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252083785 (paperback : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Indians as mascots. | Sports team mascotsSocial aspectsUnited States. | Sports spectatorsUnited StatesAttitudes. | Indians in popular cultureUnited States. | BISAC: SOCIAL SCIENCE / Ethnic Studies / Native American Studies. | SPORTS & RECREATION / History. | SPORTS & RECREATION / Sociology of Sports.

Classification: LCC GV714.5 .B55 2018 | DDC 305.897dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018020260

E-book ISBN 9780252050848

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The process of researching, writing, and advancing a book manuscript like this one is a constant evolution. During the multiyear process in which Mascot Nation unfolded, we found ourselves regularly readjusting the narratives to accommodate new information, breaking stories, and school-by-school and team-by-team developments in the mascot controversy. The development of the project, at its core, involved being willing and able to adjust to shifting ground and public sentiments, which made the constants in our process all the more meaningful.

Luckily, we both experienced many constant sources of support and encouragement as we endeavored to advance this fairly ambitious project. We wish to thank University of Illinois Pressespecially Danny Nassetfor embracing the project from its conception and for aiding us at many turns in the writing and revision process. We thank our anonymous reviewers, of both the proposal and the final product, whose contributions were as constructive as they were informative. We also must thank our two institutions, the University of Alabama and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, for providing us with the time and financial resources to be able to make this book a reality; we are also thankful that the Alabama Crimson Tide and Charlotte 49er communities embrace mascots with which we did not have to grapple and whose politics we did not have to dispute.

Andrew also wishes to thank the College of Communication and Information Sciences and the Department of Journalism and Creative Media for their steadfast support. Moreover, he extends thanks to the donors who made his Ronald Reagan Chair of Broadcasting a reality, as it provides the flexibility and resources to tackle issues such as this one with minimal compromise. He also had two doctoral students, Lauren Auverset and Fei Qiao, who worked as research assistants on various parts of this project and proved invaluable with their time and efforts. Andrew also extends heartfelt appreciation for the contributions from Jacqueline Pata, executive director of the National Congress on American Indians; her interview was essential, formulating one of the core contributions early in the book formulation. Finally, he thanks his wife, Angela, and sons, Nathan and Noah, for their constant support and interest in the mascot debate that subsumed many a dinner or car conversation.

Jason wishes to thank Danielle Endres, Casey Kelly, and Mary Stuckey, whose work on indigenist-centered contexts has been invaluable both to this project and others and, most vitally, whose friendship over the years is treasured. Two of his graduate students, Jinjie Yang and Elizabeth Ballard, assisted with gathering primary texts; both performed their tasks with precision and innovation. He also thanks C. Richard King for paving the way for indigenist-centered scholars for nearly two decades, and to Laurel Davis-Delano, who leads a weekly conversation among scholars exploring representational issues related to Native American mascots. Jason also thanks the Department of Communication at Wake Forest University, the Department of Communication at the University of Utah, and the Native American House and Department of Communication at the University of Illinois for sponsoring colloquia on his mascot work. To his colleagues and students, past and present, at the University of Alabama and UNC Charlotte, respectively, Jason expresses appreciation for the abundance of mascot conversations they have had for well over a decade. Finally, Jason is grateful to his familyJennifer, AB, and Ameliawhose love and support make life worth living and remind him that justice is something for which we daily ought to fight.

Overall, we are very pleased to present this book to audiences in a manner that heightened our authorial autonomy, allowing our vision to come into focus. We hope you find this book as meaningful as we found the process of researching and writing it.

INTRODUCTION

For Whom Does the Indian Stand? For Whom Does the Mascot Stand?

The rituals have a modicum of variance, yet common elements persist within the majority of them. For a school or a team with a Native American mascot, there typically is a drumbeatnot a snare drum but rather something more of the tom-tom, bongo, or bass drum variety. Sometimes there are weapons, ranging from spears to tomahawks; occasionally these weapons are set on fire for added effect. There is almost always a chant or song; it becomes difficult to imagine a Florida State University (FSU) football game, for instance, without humming along with the earworm that is the Seminole War Chant. Proponents of such names, images, and rituals find kinship within these consistent practices, noting that all teams enact them in some form. Opponents of Native American mascots find cause for concern, often contending that they represent issues that are disturbing, insensitive, or outright racist.

Within American sports media, there are certain topics that are assured to kindle debate among the masses. For instance, whenever a sports radio host is struggling with a slow news day, a small swath of topics are ready-made media segment fillers at any time. Some prime examples of these topics range from whether Pete Rose should be eligible for Baseball Hall of Fame induction to disagreements as to whether college athletes in revenue-generating sports should be paid a stipend for their contributions. Listeners queue up to provide their stance on such topics, convinced that their position is undeniably nuanced in comparison to the thousands of others already espoused over the course of many years. This handful of subjects consistently motivates public conversation yet rarely results in any meaningful advancement of dialogue and, certainly, any sense of conclusiveness. Such stagnation is the reason why the topics are tried-and-true controversies: resolutions are seemingly nowhere to be found.

One of these decades-long controversies has surrounded the use of Native American mascots. Sports fans debate the merits of changing the mascots in comparison to the value of maintaining the status quo; ultimately, however, little happens when it comes to making any meaningful changes. With both sides firmly entrenched in their views and with ample evidence to bolster each of their cases, there appears no easy middle ground. Perhaps one aspect that makes the mascot debate somewhat anomalous to others, though, is that both sides of the argument are seemingly undergirded with the same question posed to the other side: