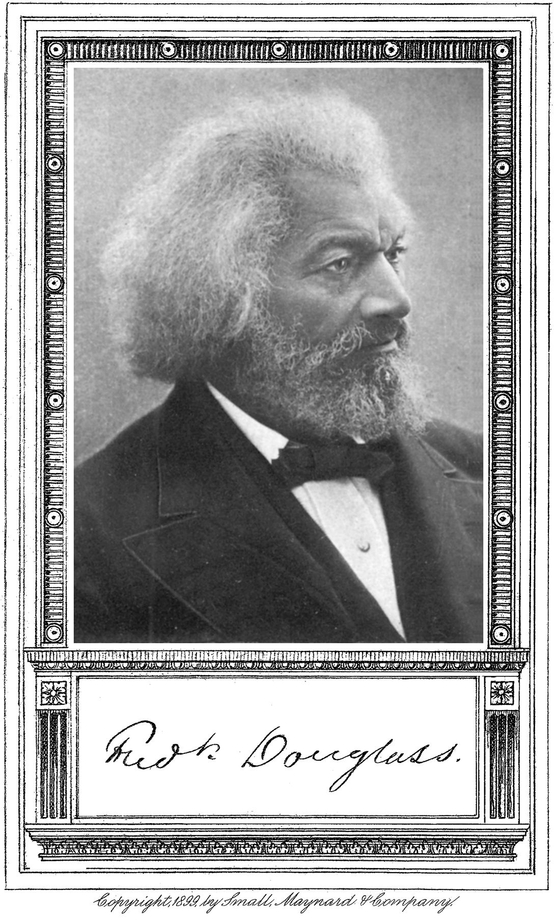

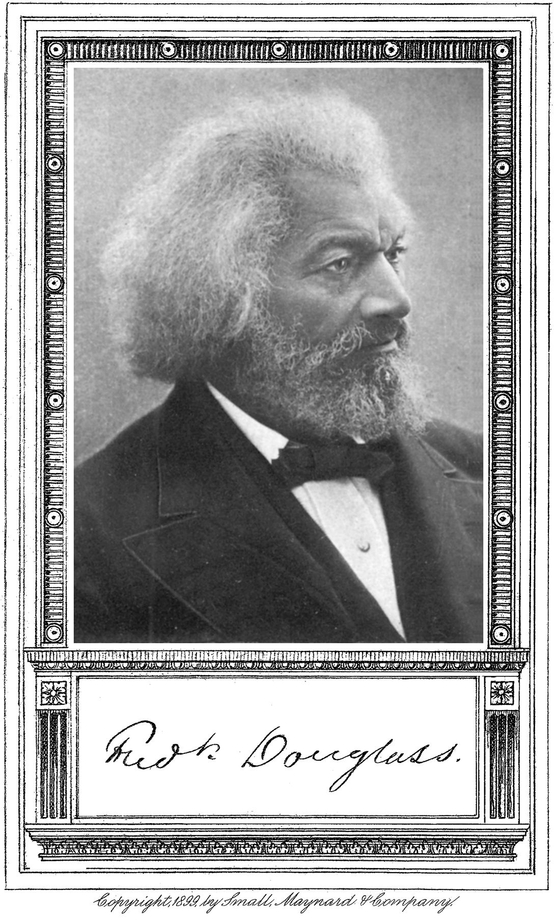

The photogravure used as a frontispiece to this volume is from a photograph by J. H. Kent, Rochester, New York, one of the last taken of Mr. Douglass. It is the portrait most highly thought of by his family, by whose permission it is used. The present engraving is by John Andrew & Son, Boston.

Copyright

About the Author, Background Notes, Introduction, editors notes, and Index copyright 2002 by Dover Publications.

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2002, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published in 1899 by Small, Maynard & Company, Boston. About the Author, Background Notes, the Introduction, the editors notes, and the index were added for the Dover edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chesnutt, Charles Waddell, 1858-1932.

Frederick Douglass I Charles Chesnutt. p.cm. Originally published: Boston : Small, Maynard, 1899, in series: The Beacon biographies of eminent Americans.

Includes bibliographical references (p.).

9780486148434

1. Douglass, Frederick, 1817?-1895. 2. African American abolitionistsBiography. 3. Abolitionists-United States-Biography. 4. Slaves-United States-Biography. 5. Antislavery movements-United States-History-19th century. I. Title.

E449.D74985 2002

973.8092d.c21

[B]

2001047756

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

42254202

www.doverpublications.com

About the Author

C harles Waddell Chesnutt (18581932) was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in the year of the famous Oberlin, Ohio, rescue of escaped slaves (made necessary by the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which put all free African Americans living in the North in great danger of being enslaved). His parents had moved to the North when life in the South became completely untenable for free African Americans. In 1866 his parents returned to North Carolina, and Charles grew up in Fayetteville, during the danger and turmoil of Reconstruction. Chesnutts fathers father, like Frederick Douglasss father, was European-Americana plantation owner who fathered seven children with an enslaved woman. Chesnutts mother also had mixed ancestry.

When he was fourteen Chesnutt began teaching in a school for African-American children. He married in 1878. Six years later he settled in Cleveland with his wife and their young children, after a brief stay in New York City in hopes of launching a literary career. He studied law and was accepted to practice as a lawyer in Ohio, but he actually supported his family as a court reporter. As Frederick Douglass noted, racism and the poverty of the vast majority of African Americans prevented the few well-educated African-American men from being able to prosper in any profession during the decades after the Civil War, as they could get neither European-American nor African-American clients.

Chesnutts story The Goophered Grapevine, published in the Atlantic magazine in 1887, was the first fiction by an African-American writer that received widespread attention from the European-American literary establishment and from European-American readers. It revealed slave life on antebellum Southern plantations and explored African-American folk culture. In 1899, in addition to his biography of Frederick Douglass, two collections of Chesnutts stories were published. The Conjure Woman was brought out in the spring by the prestigious Boston firm of Houghton Mifflin; The Wife of His Youth and Other Stories of the Color Line followed in the fall. During the next five years, three novels by Chesnutt that memorably exposed the human pain and the social costs of the U.S. heritage of chattel slaveryin particular, in relation to the color line so integral to the lives of people who had both European and African ancestrywere published. They were The House Behind the Cedars (1900), The Marrow of Tradition (1901), and The Colonels Dream (1905).

After this intensively productive period very little of Chesnutts fiction was published, but his work and its reception influenced and paved the way for the New Negro writers of the 1920s. In 1931, referring to the flourishing of African-American literary expression during the Harlem Renaissance, Chesnutt published the essay Post-BellumPre-Harlem, a retrospective look at his literary career.

Introduction

W hen Frederick Douglass arrived in New York City in September 1838 to begin life as a free man, he was entering a new and unknown world. It was not a world populated by contented people living in harmony. Even the privileged European-American males who formed the mercantile elite in the bustling port city were not having a good year.

Because young Frederick had spent quite a bit of time in the thriving Chesapeake Bay port of Baltimore (then the nations second-largest city), and because he had learned to read, he had had some access to information regarding what was happening in other parts of the United States. From newspapers and accounts given by sailors, as well as from conversations overheard on the waterfront, he would have heard about major events and issues. However, communication and transportation methods still were slow in the far-flung and fast-growing country. (Samuel F.B. Morse made a preliminary filing for his telegraph at the U.S. Patent Office in the month of Fredericks arrival in New York, but an experimental line between Washington, D.C., and Baltimore was not built until 1844.) Fredericks knowledge of living conditions in the North must have been sketchy.

In 1833 President Andrew Jackson had achieved his longtime ambition of terminating the second Bank of the United States by withdrawing all federal funds from it. New banks, which came to be known as pet banks, had been chartered in each state. In 1836 his Specie Circular had demanded that settlers pay for western land in gold or silver, not paper money. Overwrought business activity, too-easy credit, and crop failures all contributed to a difficult economic situation triggered by the major changes in banking and monetary policy. A nationwide economic depression that began with the Panic of 1837 (hundreds of bank failures) had fully taken hold, in cities, towns, and farm areas alike and would last for nearly a decade.

In New York City, about 50,000 people had lost their jobs in 1837. An estimated 6,000 had participated in the Flour Riot that winter, invading a warehouse near the City Hall. The people of the city already were reeling from the effects of the Great Fire of December 1835, which had destroyed much of the oldest section of the city. A smaller but major fire in September 1833 had destroyed the Mother A.M.E. Zion church at the corner of Church and Leonard streets, but the African-American congregation soon had rebuilt it at the same site. (Unlike the owners of the National Theater and other buildings burned in the disaster, they had had the foresight to have it fully insured for fire damage.) In October 1833 the New York City Anti-Slavery Society had been founded, with philanthropic merchant Arthur Tappan as its first president. The home of his younger brother and business partner, Lewis, was wrecked by an anti-Abolitionist mob in July 1834.