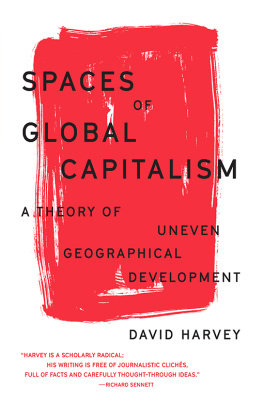

ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS: SOCIAL AND CULTURAL GEOGRAPHY

Volume 12

DAVID HARVEYS GEOGRAPHY

DAVID HARVEYS GEOGRAPHY

JOHN L. PATERSON

First published in 1984

This edition first published in 2014

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1984 J.L. Paterson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-415-83447-6 (Set)

eISBN: 978-1-315-84860-0 (Set)

ISBN: 978-0-415-73348-9 (Volume 12)

eISBN: 978-1-315-84832-7 (Volume 12)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

David Harveys Geography

John L. Paterson

CROOM HELM

London & Canberra

BARNES & NOBLE BOOKS

Totowa, New Jersey

1984 J.L. Paterson

Croom Helm Ltd, Provident House, Burrell Row,

Beckenham, Kent BR3 1AT

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Paterson, John

David Harveys geography.

1. Harvey, David, 1935 Oct. 31 2. Geography Philosophy

I. Title

910.01 G96

ISBN 0-7099-2029-6

First published in the USA 1984 by

Barnes and Noble Books

81 Adams Drive

Totowa, New Jersey, 07512

ISBN 0-389-20441-2

Printed and bound in Great Britain

CONTENTS

This book is a revised version of a thesis submitted for the Master of Philosophy degree at the University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand, in December 1980. Not only has the original work been updated and edited, but also significant sections of the study, especially the second half, have been rewritten. Unfortunately, Harveys latest book, The Limits to Capital (Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1982), was not available to me until after the completion of the revised manuscript. However, in that book Harvey confirms the analysis that I present in regarding the existence of a fundamental tension in his Marxist writings. This tension gives rise to a separation between theoretical and concrete historical analyses and the consequent problem of successfully integrating the two. In Harveys own words,

I think it is possible to transcend the seeming boundaries between theory, abstractly formulated, and history, concretely recorded; between the conceptual clarity of theory and the seemingly endless muddles of political practice. But time and space force me to write down the theory as an abstract conception, without reference to the history. In this sense the present work is, I fear, but a pale apology for a magnificent conception. And a violation of the ideals of historical materialism to boot. In self-defence I have to say that no one else seems to have found a way to integrate theory and history (The Limits to Capital, 1982, p. xiv).

I originally undertook this research on Harveys writings in order to gain some familiarity with two major philosophical influences in contemporary human geography, namely logical positivism and Marxism, and to explore the relationships between philosophy, methodology and geographical research. The emphasis in the book is therefore upon these issues rather than upon a biography of David Harvey. If some of my more critical comments prove eventually to have been misguided or unfounded, then I hope that a contribution nevertheless will have been made to the understanding of one of the most innovative and iconoclastic scholars in contemporary Anglo-American human geography.

J.L.P., Vancouver.

The research upon which this book is based was undertaken in the Department of Geography at the University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand, in 1979 and 1980. I would like to acknowledge the guidance, assistance and inspiration of teachers and friends among the staff and students of that Department. Professor Craig Duncan, my chief supervisor, actively encouraged and assisted me throughout the original project. Both Ann Magee, my second supervisor, and Lex Chalmers provided moral support and inspiration at crucial times. Lex has also rendered invaluable practical assistance. When I was employed in the Registry of the same University, I received some very practical assistance with the task of revision from friends and colleagues there. Another friend, Fletcher Cole, undertook the majority of the work on the index. Above all, I must record my thanks to my wife, Jean, and to my parents, who have unceasingly supported me in many ways.

I would like to thank Edward Arnold Ltd, London, for permission to reproduce extracts from Harveys Explanation in Geography (1969) and Social Justice and the City (1973), and the Institute of British Geographers for permission to reproduce Figures 1 and 2 from R.T. Harrison and D.N. Livingstone, Philosophy and Problems in Human Geography: a Presuppositional Approach, Area, 12, 1980, 25-31.

Finally, I would like to record my debt to the late S.S. Cameron who, in 1976, at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, guided me in my initial studies in the history and philosophy of geography. This book is dedicated to his memory and to the advancement of a genuine philosophical pluralism in geography.

1961 | I have no intention of trying to erect any elaborate mansion of theory around the conclusions already established only to find that we are still obliged to live in the shack outside (1961, p.ix) |

1967 | The student of geography can either bury his head, ostrich-like, in the sand grains of an idiographic human history, conducted over unique geographic space Or he can become a scientist The first stage of scientific investigation involves the careful testing of theories and generalization, against the facts (1967a, p. 551) |

1969 | The quest for an explanation, writes Zetterberg (1965, p. 11), is a quest for theory Without theory we cannot hope for a controlled, consistent, and rational, explanation of events. Without theory we can scarcely claim to know our own identity (1969a, pp. 89, 486) |

Geographers [have been] failing, by and large, to take advantage of the fantastic power of the scientific method (1969a, p. vi) |

1970 | Shortly after [coming to America], I happened to read Karl Marx The more I read, the more it seemed to make sense We could, Marx suggested, create a theory to explain the contradictions [of capitalism] at the same time as it would help us to overcome them. I found this very exciting and started to work at it. And lo and behold, one by one, the contradictions crumbled before the power of the analysis (1978e, p. K2) |