About This Edition

This edition is made available under the imprint of DocSouth Books, a collaborative endeavor between the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library and the University of North Carolina Press. Titles in DocSouth Books are drawn from the Librarys Documenting the American South (DocSouth) digital publishing program, online at docsouth.unc.edu. These print and downloadable e-book editions have been prepared from the DocSouth electronic editions.

Both DocSouth and DocSouth Books present the transcribed content of historic books as they were originally published. Grammar, punctuation, spelling, and typographical errors are therefore preserved from the original editions. DocSouth Books are not intended to be facsimile editions, however. Details of typography and page layout in the original works have not been preserved in the transcription.

DocSouth Books editions incorporate two pagination schemas. First, standard page numbers reflecting the pagination of this edition appear at the top of each page for easy reference. Second, page numbers in brackets within the text (e.g., [Page 9]) refer to the pagination of the original publication; online versions of the DocSouth works use this same original pagination. Page numbers shown in tables of contents and book indexes, when present, refer to the original works printed page numbers and therefore correspond to the page numbers in brackets.

Summary

Published in 1817, The Doctrines and Discipline of the African Methodist Episcopal Church was the first Discipline published by the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church. Discipline here can be thought of in one of the registers offered by the Oxford English Dictionary: instruction as given to disciples, scholars, etc.; schooling, teaching. It is a slim but definitive guide to the history, beliefs, teachings, and practices of the early A.M.E. Church. It begins with a brief history of that Church, and moves into a presentation of the Articles of Religion, including: the Trinity, the Word of God, scripture, original sin and free will, works, sacraments, baptism, Lords Supper, church ceremonies, and government. Some of the articles in this first section are quite specific, for example, the rejection of speaking in tongues in church. Immediately following the articles is an extended four-part catechism that more fully explicates the meanings and implications of the doctrinal statements.

The rest of the document is concerned with the practical matters of denominational organization. It gives guidelines for the composition and agenda of the General Conference and Yearly Conferences, specific qualifications and duties of superintendents, elders, and preachers, along with advice for the education of children. The book also takes up various kinds of united societies, providing both guidelines for duty and pitfalls to be avoided in class meetings and band societies. Proper practice and beliefs concerning marriage, dress, and liquor are covered, apparently in response to controversies at the time of its writing.

Instructions for sacramental services follow, and the book provides scripture, text, prayer, and order of service for Lords Supper, baptisms, weddings, funerals, and ordinations. The final section of the book considers concerns of the moment, a Temporal Economy that provides guidelines for preachers salaries, fundraising for home missions, the operation of a publishing venture (the A.M.E.s Book Concern) and the proscription of slaveholders in the A.M.E. Church.

Christopher Hill

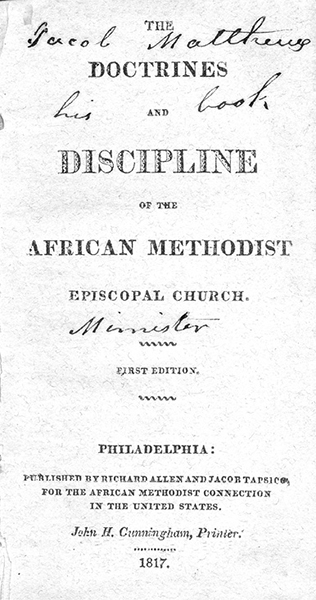

[Title Page Image]

THE DOCTRINES AND DISCIPLINE OF THE AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH.

FIRST EDITION.

PHILADELPHIA:

PUBLISHED BY RICHARD ALLEN AND JACOB TAPSICO FOR THE AFRICAN METHODIST CONNECTION IN THE UNITED STATES.

John H. Cunningham, Printer.

1817.

[Page 3] TO THE MEMBERS OF THE AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH, IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA:

Beloved Brethren,

We deem it necessary to annex to our book of discipline, a brief statement of our rise and progress, which we hope will be satisfactory, and conducive to your edification and growth in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. In November, 1787, the coloured people belonging to the Methodist Society in Philadelphia, convened together, in order to take into consideration the evils under which they laboured, arising from the unkind treatment of their white brethren, who considered them a nuisance in the house of worship, and even pulled them off their knees while in the act of prayer, and ordered them to the back seats. From these, and various other acts of unchristian conduct, we considered it our duty to devise a plan in order to build a house of our own, to worship God under our own vine and fig tree: in this undertaking, we met with great opposition from an elder of the Methodist church (J. McC.) who threatened, that if we did not give up the building, erase our names from the subscription paper, and make acknowledgments for having attempted such a thing, that in three months we should all be publicly expelled from the Methodist society. Not considering ourselves bound to obey this injunction, and being fully satisfied we should be treated without mercy, we sent in our resignations.

[Page 4]Being now as outcasts, we had to seek for friends where we could; and the Lord put it into the hearts of Dr. Benjamin Rush, Mr. R. Ralston, and other respectable citizens, to interpose for us, both by advice and assistance, in getting our building finished: Bishop White also aided us, and ordained one from among ourselves, after the order of the English church, to be our pastor.

In 1793, the number of serious people of colour, being greatly increased, they were of different opinions respecting the mode of religious worship; and, as many felt a strong partiality for that adopted by the Methodists, Richard Allen, with the advice of some of his brethren, proposed erecting a place of worship on his own ground, and at his own expense, as an African Methodist Meetinghouse. As soon as the preachers of the white Methodist church, in Philadelphia, came to the knowledge of this, they opposed it with all their might, insisting that the house should be made over to the conference, or they would publish us in the newspapers as imposing on the public, as we were not Methodists. However, the building went on, and when finished, we invited Francis Asbury, then bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, to open the house for Divine service; which invitation he accepted, and the house was named BETHEL. (See Gen. chap. 28)

It was now proposed by the resident elder, (J. McC.) that we should have the Church incorporated, that we might receive any donation or legacy, as well as enjoy other advantages arising therefrom. This was agreed to; and, in order to save expense, the elder [Page 5] proposed drawing it up for us. But, we soon found he had done it in such a manner as entirely deprived us of that liberty we expected to enjoy. So that by this stratagem, we were again brought into bondage by the white preachers.