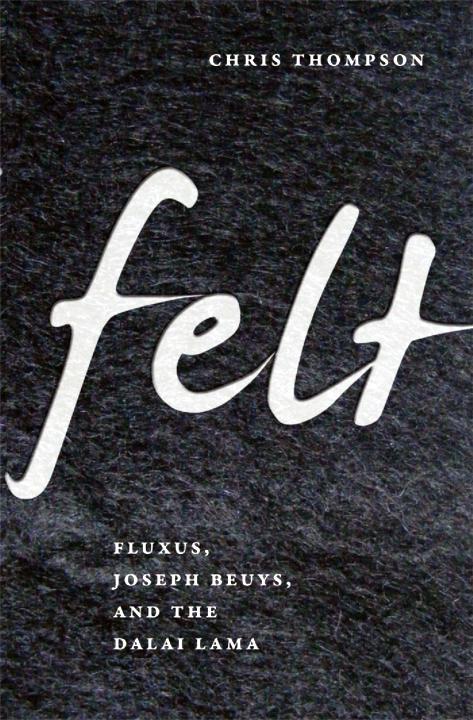

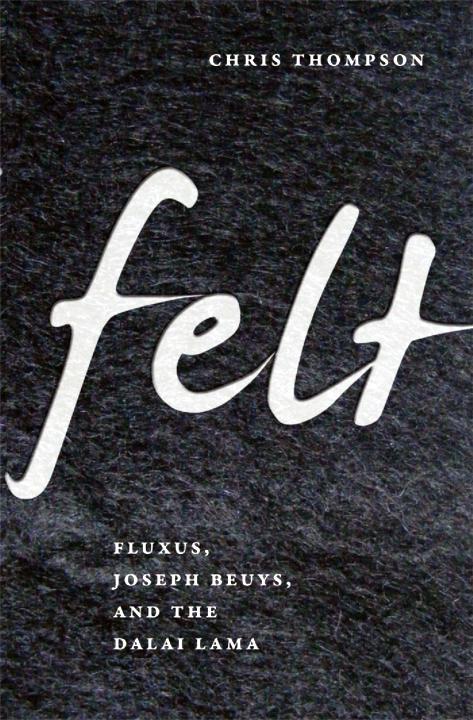

CHRIS THOMPSON

(Remember that we sometimes demand definitions for the sake not of the content, but of their form. Our requirement is an architectural one: the definition is a kind of ornamental coping that supports nothing.)

-LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN, Philosophical Investigations

Robert Filliou, Telepathique musique no. 21, Art-of-Peace Biennale, Hamburg, 1985. Photograph: Herstellung Druckhaus Hentrich, Berlin. Courtesy of Marianne Filliou.

ix

i

On January 23,1998, 1 made my first visit to Amsterdam to meet with Dutch artist and writer LouwrienWijers,who had organized the 1982 meeting between German artist Joseph Beuys and His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama of Tibet. This meeting was the subject of my Ph.D. research, which I had just begun a few months before. In fact my first step as a researcher had been to write a long letter to Wijers in October 1997, explaining my great interest in this meeting and in her work. It was the kind of heartfelt and effusive student letter that one, in looking back on it, cannot imagine writing as a "professional scholar," and it was probably precisely for this reason that it got so prompt and warm a reply, in a way that no well-seasoned prose ever could. She wrote telling me that she was delighted that someone was actually interested in this meeting and its consequences, and she invited me to come to Amsterdam as soon as I could, to meet her and begin a conversation in person. This book is the result of that conversation; it is an indirect result, in that the project that has unfolded from that point to this has been circuitous and anarchic, but a direct result in the sense that it was from precisely that momentmy receipt of that welcoming reply from an artist I had never metthat the project started.And upon its completion, of even those parts that had nothing directly to do with her, this book reveals itself to be circumscribed by that friendship in a way that makes this at once my project and her invention.

After arriving at Schiphol Airport I took the train to Amsterdam Centraal and then, following the canals, managed to find my way to Wijers's home. Just one block from it, I passed the bar that, I would soon learn, had been the favorite haunt of her close friend the Dutch performance artist Ben d'Armagnac, of whom more below. It was the last place he had been seen alive, on the evening of September 28, 1978, moments before his accidental drowning at the corner of the canals Herengracht and Brouwersgracht. A convex mirror, attached to the wall of the canal diagonally opposite from Wijers's front door and used by boat pilots to help them see oncoming vessels around the corner, today serves as a kind of makeshift memorial marking the site of his death.

Corner of Brouwersgracht and Herengracht, Amsterdam, site of d'Armagnac's death on September 28, 1978. Photograph by Chris Thompson, 2000.

Wijers answered the door with a smile, showed me to the living room, where we were to have our discussions, and to the tiny mattress piled high with wool blankets in the corner of that room, which would be my bed as well as my desk during that visit and the three that would follow-in January 1999, February 2000, and October 2004.

Atop the dresser at the foot of the bed were photographs of her deceased mother and of the Tibetan lama who had slept in the same bed during his visits to Amsterdam since the early 1980s. On the table at the head of the bed stood a small statue of the Buddha.

Wijers wanted to run an errand before we began our interview, so that we would not need to interrupt our discussion later. I looked forward to the opportunity to see a bit of Amsterdam, so agreed to walk along with her. We stepped out onto the pavement overlooking the canal. As we walked, to make conversation in the way one does as a first-time visitor, I asked her a question about Amsterdam. It was a question to which I already more or less knew the answer, because on the flight from London that morning I had begun to study the city map, which was marked with a number of tourist attractions and places of interest. I asked Wijers whether she lived near Anne Frank's house. She smiled and said,"Yes, it is very near." I asked whether she had ever been to see it.The air was cold and the sky was gray with the hint of a snow that never did come."No, in fact I have never been inside there." She looked at me then, with a smile connecting her cheeks. She told me that the whole of Amsterdam was Anne Frank's house.

"He's drunk," his wife said as she entered the room with my wife."He always gets drunk when you show up.... And when he gets drunk he thinks he's a poet or a philosopher."'

Years ago, when I was an undergraduate student, during one of several late-night drunken conversations with one of my good friends, our meandering efforts at erudition led us to stumble into a discussion of a short poem he had recently written.

I told him, pulling forth pearls of the wisdom gleaned from several weeks spent in my Hinduism, Buddhism,Taoism class, that it sounded like Lao-Tzu.This prompted him to tell me of a phrase he had always loved, one that he felt sure came from the writings of some obscure Taoist sage whose name he could not recall. We delighted in this uncertainty like young undergraduates: much better, much more fitting, that the author was unknown. The phrase, the jewel of Taoist insight, was: "It loves to happen." What matter who said it, we two sages said! Bottoms up!

Next page