NEANDERTHAL

NEANDERTHAL

NEANDERTHAL MAN AND THE STORY OF HUMAN ORIGINS

PAUL JORDAN

First published in 1999 by Sutton Publishing

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

Paul Jordan, 1999, 2013

The right of Paul Jordan, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9480 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

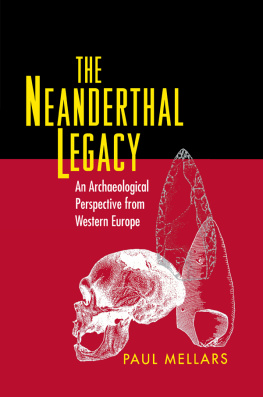

The author would like to thank Dr Robert Foley of the Department of Biological Anthropology, Cambridge University, for his generous permission to photograph the casts in the departments collection, and his assistant Maggie Bellatti for her help with the photography. All photographs were taken by the author unless otherwise stated particular thanks go to the Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann, Germany, for their colour pictures. Thanks are also due to Dr John Wymer for the use of his drawing of the Molodova finds and to Chicago University Press for permission to reproduce the jaw picture from The Middle Stone Age at Klasies River Mouth by Ronald Singer and John Wymer. Special thanks go to Professor Paul Mellars of Cambridge University for many helpful conversations in the course of writing this book.

List of illustrations

Black and White Illustrations

Neanderthal half pelvis from Kebara.

Homo habilis (right) with 1470, which may represent another related but more evolved species.

Colour plates

(between pp. 112 and 113)

Introduction

The Man from Newmandale

The very name Neanderthal makes an impact all by itself and so, if you prefer it, does Neandertal, without the h. The branch of fate that determines the names (and thereby the flavours) assigned to our various remote ancestors and the productions they left behind them Cr-Magnon, Magdalenian, Oldowan, Heidelberg and all the rest has endowed Neanderthal Man with the most flavourful name of them all. Germanic but with more than a hint of the classical, the name looks strong on the page and, however pronounced, sounds as strong to the ear. Especially when mispronounced by English-speakers, it carries a powerful charge of primitive and cloddish associations: knee-and-earthal, a fitting name for the bent and shuffling cave-man, hardly risen up out of the mud, that popular imagination still too often imagines Neanderthal Man to have been. Nayandertaal sounds cleaner altogether. Because the name starts with N and contains (at least in its older spelling) the th combination, a surprisingly large number of people go on to confuse Neanderthal Man with the Neolithic period, to the detriment of the latter, imagining that innovative time of the first farmers to have been the heyday of the shuffling cavemen. In fact, the last of the Neanderthal people missed the Neolithic by more than twenty thousand years.

The German spelling reforms at the start of the twentieth century removed the h from Thal and so from the name of the dale in North RhineWestphalia after which Neanderthal Man was called. By then, the scientific world was committed to the classification Homo neanderthalensis with the h in place, but we are at liberty to write either Neanderthal or Neandertal in common usage concerning this fossil man. With its nineteenth-century echoes of the beginnings of scientific anthropology, Neanderthal appeals, but theres no doubt that Neandertal would help English speakers to pronounce the name more accurately: most American and Continental writers prefer it, but the British often stick with Neanderthal.

The Neander Dale was an appropriate place in which to find the first correctly identified remains of an earlier form of Man, distinct from the modern worldwide species Homo sapiens sapiens. The old bones from the Neandertal were evidence of a form of Man new to science in the middle of the nineteenth century: a New Man indeed for the contemplation of both the scientific and the wider world of the time. A nice turn of fate, then, that this New Man should have been discovered in a valley named, circuitously, after a new man of the seventeenth century, who came from a family with the unremarkable name of Neumann (Newman in English). He was the vicar of St Martins, Dsseldorf, where he was also the organist, and a composer of hymns. As we could expect of a clergyman of his time, he was a classical scholar, too, and headmaster of the towns Latin College. He chose to use a Graecized form of his name for his hymn-writing, and you can come across Neander in hymn books to this day. In his late twenties, he often liked to pass his time, composing no doubt, in a particular little valley close to his home and the locals soon called the place after him, Neanderthal = Newmandale. And when the bones discovered in a quarry in the valley in 1856 came to be assigned to Neanderthal Man, a New Man in the human story was recognized for the first time.

Nearly 150 years after his first discovery, the New Man from the Neanderthal may sometimes seem a bit old hat now, overshadowed by the more recent discoveries of much older and much more primitive types like Homo erectus (first encountered in Java and China) and the early men and pre-men of East and Southern Africa. A lot more New Men and Near Men and Ape Men have come on the scene since Neanderthal Man put in his first appearance. These more recent arrivals have rightly had their due since they belong to the very early and crucial epochs of human evolution, when the first decisive steps towards hominization or anthropogenesis were taken, without which we would not be here to be interested in our origins. But interest, including scientific interest, in those earliest phases of the human story has perhaps reached the point where the newcomers who continue to back into the limelight, especially on the very old sites of East Africa have too far upstaged the old hands like Neanderthal Man, who still has a lot to tell us about the mysteries of the origin and nature of fully modern man: precisely because he is closer to us by far than the ape-men and early men of Africa and elsewhere closer, but not the same. For Neanderthal Man is the real alien with whom the human race was once in contact, in circumstances over which there has been a great deal of scholarly debate. Our popular culture is obsessed with the idea of aliens from outer space, endowed with intelligence and purpose (often hostile) but skewed away from us in some essential way, different in outlook and desire. It is highly unlikely, to say the least, that any aliens from outer space have ever come anywhere near our Earth, but it is certain that human beings of the modern sort (that is to say representatives of the species Homo sapiens sapiens, to which every member of the human race today belongs) have in the not so remote past shared parts of the world with forms of human being significantly different from themselves, both physically and, it must be, psychologically too. The Neanderthalers of Europe and Western Asia are the type par excellence of this sort of alien neighbour. How different they were has recently been a matter of fierce debate among anthropologists and up to a point may always be so, but for the moment a trend in thinking fuelled by new evidence from the field of genetics is unmistakably pointing in a particular direction. So on the grounds both of the new scientific evidence and of this particular fossil mans perennial capacity to throw light on our own nature and origin, a fresh account of the life and times of Neanderthal Man may be timely.