Laurence C. Smith

The World in 2050:

Four Forces Shaping Civilization's Northern Future

For my brilliant, beautiful Abbie,

who is a part of this story

PROLOGUE

Flying into Fort McMurray

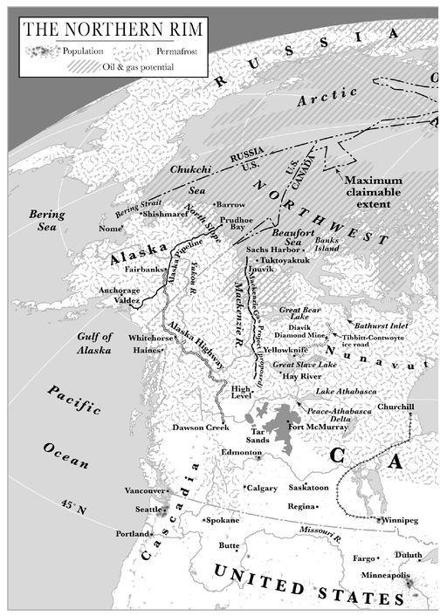

My nose was pressed against the rear window glass of a Boeing 747. It was a direct flight from Edmonton to the booming new oil city of Fort McMurray, Alberta, in the broad belt of boreal forest that girdles the globe through Alaska, Canada, Scandinavia, and Russia. The scene below morphed from urban concrete to canary-yellow canola fields, then gradually from fields to a deep shag carpet of evergreen forest jeweled with bogs. The forest was crisscrossed here and there by roads, and patched with clearings, but grew more desolate by the minute. In under an hour, the transformation from urban metropolis to farmland to wilderness was complete.

Then, suddenly, the woods dissolved into gleaming homes, the newest residential subdivision of Fort McMurray. Freshly cut survey lines radiated outward in all directions through the woods. Bulldozers and work crews ground away at roadbeds and building pads, engraving a sort of master blueprint into the landscape for hundreds more homes in waiting. Small wonder. The median price of a home in Fort McMurray had just surged to $442,000, more than $100,000 higher than in my home city of Los Angeles.1 The aggressive transformation taking place beneath my window was just one of many I was about to see over the next fifteen months.

This was not my first trip to the North. Id already been studying cold, remote places for fourteen years, beginning with a doctoral dissertation studying the Iskut River, a tree-tossing torrent that rips through a remote corner of British Columbia. Something about the rawness of the place, the sense of danger and frontier, hooked me hard. The sight of fresh grizzly-bear footprints, smashed just minutes before over my own, was a shivery thrill. I finished school, became a geography professor at UCLA, and started a long series of research projects in Alaska, Canada, Iceland, and Russia.

My specialty was the geophysical impacts of climate change. In the field I would measure stream flows, survey glacier snouts, sample soil, and the like. Back home in Los Angeles I would continue the research from my desk, extracting numbers from satellite data like little digital polyps. But all this would change in 2006. The flight to Fort McMurray was the beginning of my attempt to gain deeper understanding of other phenomena now unfolding around the northern quarter of our planet, and how they fit in with even bigger global forces reverberating throughout the world as a whole.

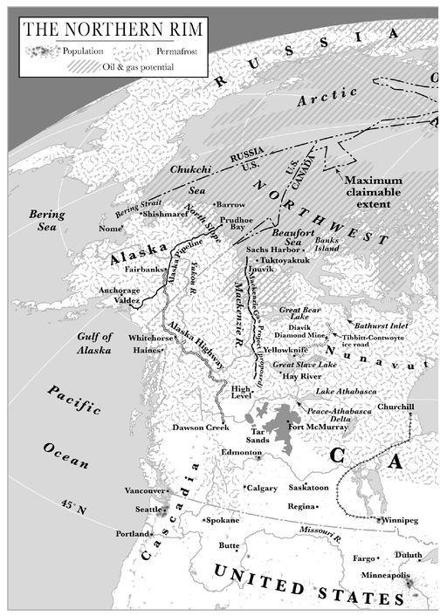

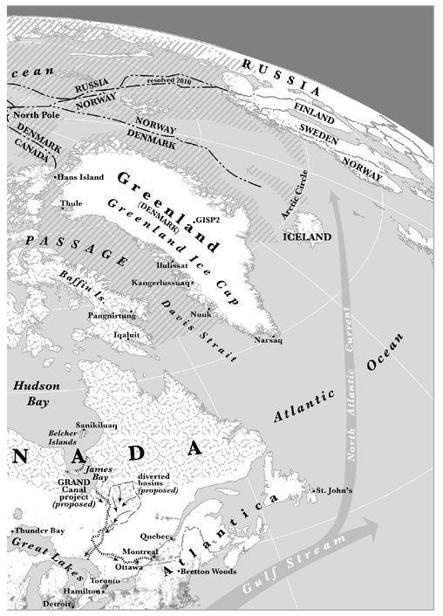

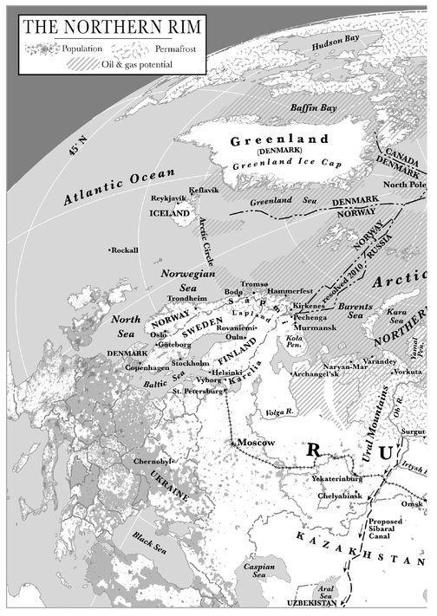

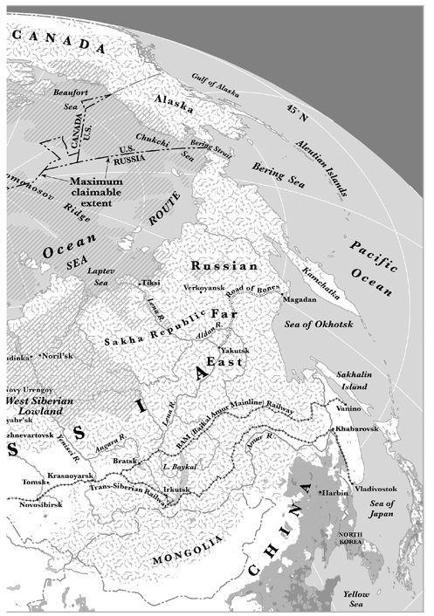

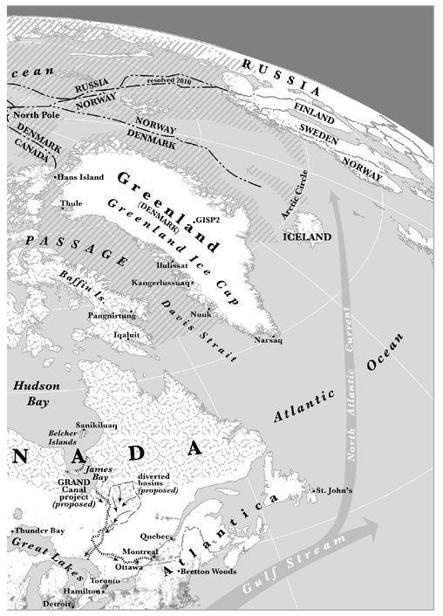

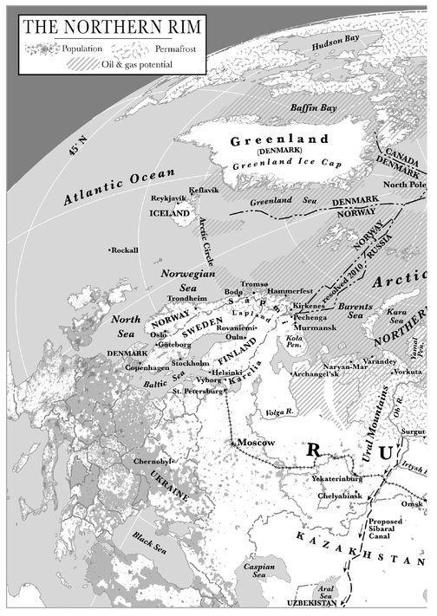

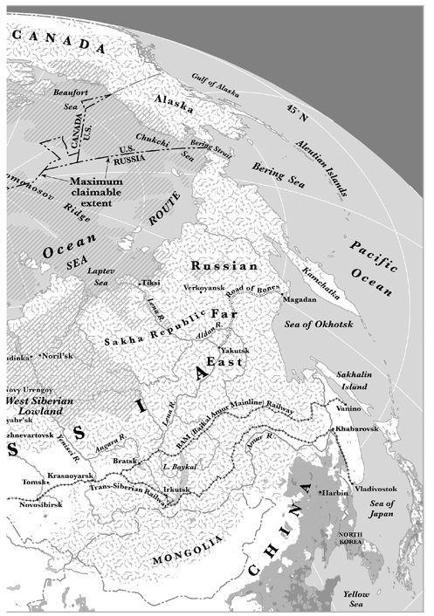

From my scientific research, I knew that amplified climate warming had begun in the North, but what might that mean for the regions people and ecosystems? What about its ongoing political and demographic trends, or the vast fossil fuel deposits thought to exist beneath its ocean floors? How would it be transformed by even bigger pressures building around the world? And if, as many climate models suggest, our planet becomes one of killer heat waves, fickle rain, and baked croplands, might new human societies emerge in places currently unappealing for settlement? Could the twenty-first century see the decline of the southwestern United States and European Mediterranean, but the ascent of the northern United States, Canada, Scandinavia, and Russia? The more I looked, the more it seemed this northern geographic region was highly relevant to the future of us all.

I was about to burn through almost two years of my life going to places youve heard of, like Toronto, Helsinki, and Cedar Rapids, and others you maybe havent, like High Level, Troms, and the Belcher Islands. I was about to fly on helicopters and airplanes, rent cars, ride buses and trains, and live on a ship. My goal was to see with my own eyes what is happening with these places, and to ask the scientists, business owners, politicians, and ordinary residents who live and work in them what they saw happening and where they thought things might be heading. After studying it for years, I was about to discover the Northand its broader importance to our futurefor the very first time.

CHAPTER 1

Martells Hairy Prize

Prediction is very difficult. Especially about the future.

Niels Bohr (1885-1962)

The future is here. Its just not evenly distributed yet.

William Gibson (1948-)

On a cold April day in 2006, Jim Martell, a sixty-five-year-old businessman from Glenns Ferry, Idaho, shot and killed a strange beast. Cradling his rifle, he ran with his guide, Roger Kuptana, to where it lay slumped on the snow. Both men wore thick parkas as protection against the icy wind. They were on Banks Island, high in the Canadian Arctic, some 2,500 miles north of the U.S. border.

Martell was an avid big-game hunter and had paid about forty-five thousand dollars for the right to bag Ursus maritimus, a polar bear, one of the most coveted trophies of his sport. Kuptana was an Inuit tracker and guide who lived in the nearby village of Sachs Harbor. Polar bear hunting is strictly regulated but legal in Canada, and the hefty license and guide fees provide important revenue to Sachs Harbor and other Inuit towns like it. Martell had permission to take down a polar bear and only a polar bear. But that was not what lay bleeding in the snow.

At first glance the creature looked well enough like a polar bear, albeit a small one. It was seven feet long and covered with creamy white fur. However, its back, paws, and nose were mottled with patches of brown. There were dark rings, like a pandas, around its eyes. The creatures face was flattened, with a humped back and long claws. In fact, it had many of the features of Ursus arctos horribilis, the North American grizzly bear.

Martells bear triggered an international sensation. Canadian wildlife officials seized the body and submitted DNA samples to a genetics lab to find out what it was. Tests confirmed the animal was indeed a half-breed, the product of a grizzly bear father and a polar bear mother.2 It was the first evidence of grizzly/polar bear copulation ever reported in the wild. News outlets announced the arrival of a Hairy Hybrid3 and the blogosphere erupted with either wonderment and proposed namespizzly? grizzlar? grolar bear?or outrage that the only known specimen had been shot dead. A Save the Pizzly Web site hawked T-shirts, coffee mugs, and stuffed dolls. Martell was subjected to angry criticism; in response he pointed out that the world would never have learned of the thingwhatever it was calledif not for his fine shot.

For this bizarre tryst even to have happened required that a grizzly wander far north into polar bear territory, a formerly rare phenomenon that biologists are now beginning to see more often. Journalists were quick to make a climate change connection: Was this, they wondered, a preview of natures response to global warming? But scientists like Ian Stirling, a leading polar bear biologist, were rightly skeptical of drawing strong conclusions from what was, after all, an isolated event. That changed in 2010, when a second specimen was shot. Tests confirmed it was the offspring of a hybrid mother; in other words,