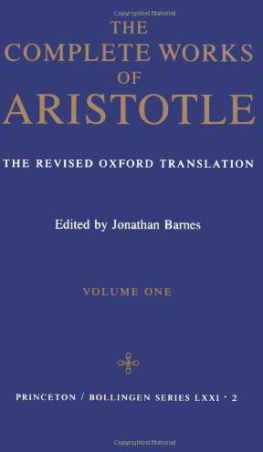

BOLLINGEN SERIES LXXI 2

THE

COMPLETE WORKS OF

ARISTOTLE

THE REVISED OXFORD TRANSLATION

Edited by

JONATHAN BARNES

VOLUME ONE AND TWO

Copyright1984 by The Jowett Copyright Trustees

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William St.,

Princeton, New Jersey

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

THIS IS PART TWO OF THE SEVENTY-FIRST

IN A SERIES OF WORKS SPONSORED

BY BOLLINGEN FOUNDATION

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A RISTOTLE.

The complete works of Aristotle.

(Bollingen series ; 71:2)

Includes index.

1. PhilosophyCollected works, I. Barnes, Jonathan. II. Title. III. Series.

B407.S6 1984 185 82-5317

ISBN-13: 978-0-691-01650-4

Princeton University Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources

Printed in the United States of America

Second Printing, 1985

Fourth Printing, 1991

Sixth Printing, with Corrections, 1995

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13

ISBN-13: 978-0-691-01650-4

ISBN-10: 0-691-01650-X

CONTENTS

Volume One |

|---|

Volume Two |

: See the Note to the Reader |

PREFACE

BENJAMIN JOWETT published his translation of Aristotles Politics in 1885, and he nursed the desire to see the whole of Aristotle done into English. In his will he left the perpetual copyright on his writings to Balliol College, desiring that any royalties should be invested and that the income from the investment should be applied in the first place to the improvement or correction of his own books, and secondly to the making of New Translations or Editions of Greek Authors. In a codicil to the will, appended less than a month before his death, he expressed the hope that the translation of Aristotle may be finished as soon as possible.

The Governing Body of Balliol duly acted on Jowetts wish: J. A. Smith, then a Fellow of Balliol and later Waynflete Professor of Moral and Metaphysical Philosophy, and W. D. Ross, a Fellow of Oriel College, were appointed as general editors to supervise the project of translating all of Aristotles writings into English; and the College came to an agreement with the Delegates of the Clarendon Press for the publication of the work. The first volume of what came to be known as The Oxford Translation of Aristotle appeared in 1908. The work continued under the joint guidance of Smith and Ross, and later under Rosss sole editorship. By 1930, with the publication of the eleventh volume, the whole of the standard corpus aristotelicum had been put into English. In 1954 Ross added a twelfth volume, of selected fragments, and thus completed the task begun almost half a century earlier.

The translators whom Smith and Ross collected together included the most eminent English Aristotelians of the age; and the translations reached a remarkable standard of scholarship and fidelity to the text. But no translation is perfect, and all translations date: in 1976, the Jowett Trustees, in whom the copyright of the Translation lies, determined to commission a revision of the entire text. The Oxford Translation was to remain in substance its original self; but alterations were to be made, where advisable, in the light of recent scholarship and with the requirements of modern readers in mind.

The present volumes thus contain a revised Oxford Translation: in all but three treatises, the original versions have been conserved with only mild emendations. (The three exceptions are the Categories and de Interpretatione, where the translations of J. L. Ackrill have been substituted for those of E. M. Edgehill, and the Posterior Analytics, where G. R. G. Mures version has been replaced by that of J. Barnes. The new translations have all been previously published in the Clarendon Aristotle series.) In addition, the new Translation contains the tenth book of the History of Animals, and the third book of the Economics, which were not done for the original Translation; and the present selection from the fragments of Aristotles lost works includes a large number of passages which Ross did not translate.

In the original Translation, the amount and scope of annotation differed greatly from one volume to the next: some treatises carried virtually no footnotes, others (notably the biological writings) contained almost as much scholarly commentary as textthe work of Ogle on the Parts of Animals or of dArcy Thompson on the History of Animals, Beares notes to On Memory or Joachims to On Indivisible Lines, were major contributions to Aristotelian scholarship. Economy has demanded that in the revised Translation annotation be kept to a minimum; and all the learned notes of the original version have been omitted. While that omission represents a considerable impoverishment, it has reduced the work to a more manageable bulk, and at the same time it has given the constituent translations a greater uniformity of character. It might be added that the revision is thus closer to Jowetts own intentions than was the original Translation.

The revisions have been slight, more abundant in some treatises than in others but amounting, on the average, to some fifty alterations for each Bekker page of Greek. Those alterations can be roughly classified under four heads.

(i) A quantity of work has been done on the Greek text of Aristotle during the past half century: in many cases new and better texts are now available, and the reviser has from time to time emended the original Translation in the light of this research. (But he cannot claim to have made himself intimate with all the textual studies that recent scholarship has thrown up.) A standard text has been taken for each treatise, and the few departures from it, where they affect the sense, have been indicated in footnotes. On the whole, the reviser has been conservative, sometimes against his inclination.

(ii) There are occasional errors or infelicities of translation in the original version: these have been corrected insofar as they have been observed.

(iii) The English of the original Translation now seems in some respects archaic in its vocabulary and in its syntax: no attempt has been made to impose a consistently modern style upon the translations, but where archaic English might mislead the modern reader, it has been replaced by more current idiom.

(iv) The fourth class of alterations accounts for the majority of changes made by the reviser. The original Translation is often paraphrastic: some of the translators used paraphrase freely and deliberately, attempting not so much to English Aristotles Greek as to explain in their own words what he was intending, to conveythus translation turns by slow degrees into exegesis. Others construed their task more narrowly, but even in their more modest versions expansive paraphrase from time to time intrudes. The revision does not pretend to eliminate paraphrase altogether (sometimes paraphrase is venial; nor is there any precise boundary between translation and paraphrase); but it does endeavor, especially in the logical and philosophical parts of the

Next page