THE PHILOSOPHERS PLANT

AN INTELLECTUAL HERBARIUM

MICHAEL MARDER

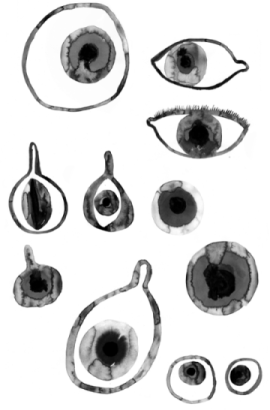

DRAWINGS BY MATHILDE ROUSSEL

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2014 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53813-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Marder, Michael, 1980

The philosophers plant : an intellectual herbarium / Michael Marder; with drawings by Mathilde Roussel.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16902-8 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-16903-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-53813-8 (e-book)

1. BotanyPhilosophy. 2. BotanyHistory.

3. PlantsAdaptation. 4. Human-plant relationships. I. Title.

QK46.M36 2014

580dc23

2014010349

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

COVER DESIGN: MATHILDE ROUSSEL

BOOK DESIGN & TYPESETTING: VIN DANG

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing.

Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

For Patrcia

To grow together

All my botanical walks, the varied impressions made on me by the places where I have seen striking things, the ideas they have stirred in me, and the incidents connected to them have all left me with the impressions, which are renewed by the sight of the plants I collected in those very places. [A]ll I have to do is open my herbarium and it quickly transports me there.

JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU, REVERIES OF THE SOLITARY WALKER

[The] flowers are of course dry and life has vanished from them. But what on earth is a living thing if the spirit of man does not breathe life into it? What is speechless but that to which man does not lend his speech?

G. W. F. HEGEL, LETTER TO NANETTE ENDEL, JULY 2, 1797

There is, absent from every garden, a dried flower in a book

JACQUES DERRIDA, MARGINS OF PHILOSOPHY

Not enough time to come and go around a thought, not enough time to make the herbarium of thoughts

HLNE CIXOUS, MANNA: FOR THE MANDELSTAMS, FOR THE MANDELAS

CONTENTS

This book reconsiders Western philosophy from the perspective of plant life, which has been systematically marginalized throughout its history. Given the vast scope of the subject, it will be impossible for me to thank everyone who has indirectly contributed to this project. I cannot, however, fail to mention the inestimable support that Wendy Lochner of Columbia University Press has provided to The Philosophers Plant since its very inception. Luis Garagalza has been my interlocutor in the last few years and has indicated a number of sources crucial for . Alan Read and the participants in a daylong event, Plant Science, at Kings College, London, which took place in May 2013, have helped me sharpen my thoughts on the place of plants and on the relation between Platos and Heideggers approaches to the vegetal. In June 2013, students in my Critical Plant Studies seminar at the Forum for Contemporary Theory at the University of Goa, India, have provided valuable feedback on the second half of the manuscript. Luce Irigaray has been generous in her comments on the chapter dedicated to her work. Mathilde Roussels creativity, expressed in beautiful and thought-provoking drawings, has turned The Philosophers Plant into a veritable intellectual herbarium. Patrcia Vieira has been a constant companion in the practical and theoretical contemplations of vegetal nature. This book is a small token of my gratitude to her.

were published on my blog, The Philosophers Plant, hosted by The Los Angeles Review of Books. All these texts are reproduced with the permission of the copyright holders.

Few among the intellectual giants of the West professed a greater love for plants than Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Through his immersion in a meticulous study of botany, which surpassed the limited scope of an empirical science and became for him an instance of lart divin, the philosopher hoped to get back to our natural origins, which were obstructed by the perversions of civilization. Alexandra Cook fittingly grouped Rousseaus botanical reflections and practices under the heading of the salutary science, a therapy for curing the modern soul by purging it of destructive passions and putting it back in touch with the simplicity, calm, and truth of nature.

In light of this sublime botany, philosophy itself changes beyond recognition: philo-sophia, the love of wisdom, is brought to life with the help of phyto-philia, the love of plants.

Already for Socrates, care for the soul was a preeminent philosophical concern. The goal of philosophy was to save the soul from its corruption and degradation by putting it in touch with its immortal provenance in the realm of Ideas. Much of the Western intellectual history that ensued accepted, without questioning, the Socratic recipe for salvation: thought had to discover a way back to its own immutable logical, metaphysical, and ontological foundations so as to dwell there in a lasting respite from the vicissitudes of everyday reality. The utopian, placeless place of salvation, exempt from the effects of time, is at the furthest remove from the plant, for which constant change and the environment wherein it flourishes are paramount. That is probably why most philosophers were not phytophiles but instead viewed growth along with its unavoidable double, decay, as anathema to true philosophizing.