Also by Neil deGrasse Tyson

The Sky Is Not the Limit: Adventures of an Urban Astrophysicist

Cosmic Horizons: Astronomy at the Cutting Edge

(with Steven Soter, eds.)

One Universe: At Home in the Cosmos (with Charles Liu and Robert Irion)

Universe Down to Earth

Just Visiting This Planet

Merlins Tour of the Universe

Also by Donald Goldsmith

Chaos to Cosmos: A Space Odyssey

(with Laura Danly and Leonard David)

Connecting with the Cosmos: Nine Ways to Experience the Wonder of the Universe

The Search for Life in the Universe (with Tobias Owen; 3rd ed.)

The Runaway Universe: The Race to Find

the Future of the Cosmos

The Ultimate Planets Book

Worlds Unnumbered: The Search for Extrasolar Planets

The Ultimate Einstein (with Robert Libbon)

Einsteins Greatest Blunder? The Cosmological Constant and

Other Fudge Factors in the Physics of the Universe

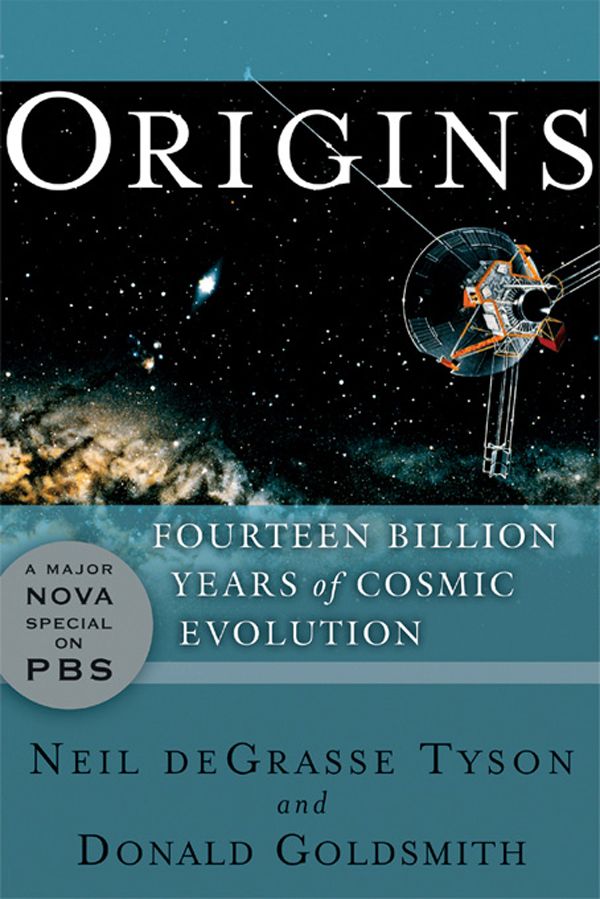

Fourteen Billion Years of

Cosmic Evolution

Neil deGrasse Tyson

and

Donald Goldsmith

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

To all those who look up,

And to all those who do not yet know

why they should

Contents

Acknowledgments

For reading and rereading the manuscript, ensuring that we mean what we say and say what we mean, we are indebted to Robert Lupton of Princeton University. His tandem expertise in astrophysics and the English language allowed the book to reach several notches higher than we had otherwise imagined for it. We are also grateful to Sean Carroll at Chicagos Fermi Institute, Tobias Owen of the University of Hawaii, Steven Soter of the American Museum of Natural History, Larry Squire of UC San Diego, Michael Strauss of Princeton University, and PBS NOVA producer Tom Levenson for key suggestions that improved several parts of the book.

For expressing confidence in the project from the beginning, we thank Betsy Lerner of the Gernert Agency, who saw our manuscript not only as a book but also as an expression of deep interest in the cosmos, deserving the broadest possible audience with whom to share the love.

Major portions of Part II and scattered portions of Parts I and III first appeared as essays in Natural History magazine by NDT. For this, he is grateful to Peter Brown, the magazines editor in chief, and especially to Avis Lang, their senior editor, who continues to work heroically as a learned literary shepherd to NDTs writing efforts.

The authors further recognize support from the Sloan Foundation in the writing and preparation of this book. We continue to admire their legacy of support for projects such as this.

Neil deGrasse Tyson, New York City

Donald Goldsmith, Berkeley, California

June 2004

PREFACE

A Meditation on the Origins of Science and the Science of Origins

A new synthesis of scientific knowledge has emerged and continues to flourish. In recent years, the answers to questions about our cosmic origins have not come solely from the domain of astrophysics. Working under the umbrella of emergent fields with names such as astrochemistry, astrobiology, and astro-particle physics, astrophysicists have recognized that they can benefit greatly from the collaborative infusion of other sciences. To invoke multiple branches of science when answering the question, Where did we come from? empowers investigators with a previously unimagined breadth and depth of insight into how the universe works.

In Origins: Fourteen Billion Years of Cosmic Evolution , we introduce the reader to this new synthesis of knowledge, which allows us to address not only the origin of the universe but also the origin of the largest structures that matter has formed, the origin of the stars that light the cosmos, the origin of planets that offer the likeliest sites for life, and the origin of life itself on one or more of those planets.

Humans remain fascinated with the topic of origins for many reasons, both logical and emotional. We can hardly comprehend the essence of anything without knowing where it came from. And of all the stories that we hear, those that recount our own origins engender the deepest resonance within us.

Self-centeredness bred into our bones by our evolution and experience on Earth has led us naturally to focus on local events and phenomena in the retelling of most origin stories. However, every advance in our knowledge of the cosmos has revealed that we live on a cosmic speck of dust, orbiting a mediocre star in the far suburbs of a common sort of galaxy, among a hundred billion galaxies in the universe. The news of our cosmic unimportance triggers impressive defense mechanisms in the human psyche. Many of us unwittingly resemble the man in the cartoon who gazes at the starry heavens and remarks to his companion, When I look at all those stars, Im struck by how insignificant they are.

Throughout history, different cultures have produced creation myths that explain our origins as the result of cosmic forces shaping our destiny. These histories have helped us to ward off feelings of insignificance. Although origin stories typically begin with the big picture, they get down to Earth with impressive speed, zipping past the creation of the universe, of all its contents, and of life on Earth, to arrive at long explanations of myriad details of human history and its social conflicts, as if we somehow formed the center of creation.

Almost all the disparate answers to the quest of origins accept as their underlying premise that the cosmos behaves in accordance with general rules, which reveal themselves, at least in principle, to our careful examination of the world around us. Ancient Greek philosophers raised this premise to exalted heights, insisting that we humans possess the power to perceive how nature operates, as well as the underlying reality beneath what we observe: the fundamental truths that govern all else. Quite understandably, they insisted that uncovering those truths would be difficult. Twenty-three hundred years ago, in his most famous reflection on our ignorance, the Greek philosopher Plato compared those who strive for knowledge to prisoners chained in a cave, unable to see objects behind them, and who must attempt to deduce from the shadows of these objects an accurate description of reality.

With this simile, Plato not only summarized humanitys attempts to understand the cosmos but also emphasized that we have a natural tendency to believe that mysterious, dimly sensed entities govern the universe, privy to knowledge that we can, at best, glimpse only in part. From Plato to Buddha, from Moses to Mohammed, from a hypothesized cosmic creator to modern films about the matrix, humans in every culture have concluded that higher powers rule the cosmos, gifted with an understanding of the gulf between reality and superficial appearance.

Half a millennium ago, a new approach toward understanding nature slowly took hold. This attitude, which we now call science, arose from the confluence of new technologies and the discoveries that they fostered. The spread of printed books across Europe, together with simultaneous improvements in travel by road and water, allowed individuals to communicate more quickly and effectively, so that they could learn what others had to say and could respond far more rapidly than in the past. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, this hastened back-and-forth disputation and led to a new way of acquiring knowledge, based on the principle that the most effective means of understanding the cosmos relies on careful observations, coupled with attempts to specify broad and basic principles that explain a set of these observations.

Next page