Table of Contents

For Gideon and Veronica

PREFACE

The Choice

H UNDREDS OF MILLIONS of people are at risk of becoming the victims of genocide and related violence.

They live in countries governed by political regimes that have been and are inherently prone to committing mass murder. In some countries, such as Sudan, the killing is ongoing. In others, such as Rwanda, the killing has been recent. In still others, such as Kenya, the threat of mass murder has appeared real if not imminent. In yet others, although no warning signals suggest immediate danger, mass slaughter could begin precipitously.

Our time, dating from the beginning of the twentieth century, has been afflicted by one mass murder after another, so frequently and, in aggregate, of such massive destructiveness, that the problem of genocidal killing is worse than war. Until now, the worlds peoples and governments have done little to prevent or stop mass murdering. Today, the world is not markedly better prepared to end this greatest scourge of humanity. The evidence of this failure is overwhelming. It is to be found in Tibet, North Korea, the former Yugoslavia, Saddam Husseins Iraq, Rwanda, southern Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Darfur.

Individuals, institutions, and governments, in every region of the worldwe all have a choice:

We can persist in our malign neglect that consists of three parts: failing to face the problem squarely and to understand the real nature of genocide; failing to recognize we can far more effectively protect hundreds of millions of people and radically reduce mass murders incidence; and failing to choose to act on this knowledge.

Or we can focus on this scourge; understand its causes, its nature and complexity, and its scope and systemic quality; and, building upon that understanding, craft institutions and policies that will save countless lives and also lift the lethal threat under which so many people live.

How can we not choose the second?

INTRODUCTION

CLARIFYING THE ISSUES

CHAPTER ONE

Eliminationism, Not Genocide

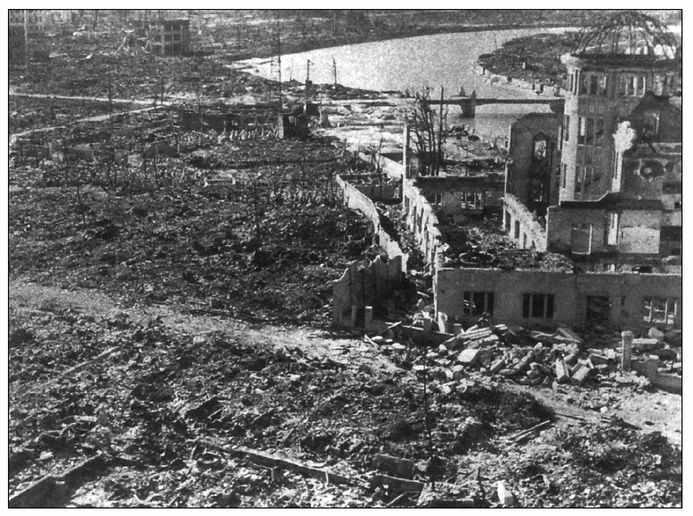

H ARRY TRUMAN, THE THIRTY-THIRD president of the United States, was a mass murderer. He twice ordered nuclear bombs dropped on Japanese cities. The first, an atomic bomb, exploded over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and the second, a nuclear bomb, detonated over Nagasaki on August 9. Truman knew that each would kill tens of thousands of Japanese civilians who had no direct bearing on any military operation, and who posed no immediate threat to Americans. In effect, Truman chose to snuff out the lives of approximately 300,000 men, women, and children. Upon learning of the first bombs annihilation of Hiroshima, Truman was jubilant, announcing that this is the greatest thing in history. He then followed up in Nagasaki with a second greatest thing. It is hard to understand how any right-thinking person could fail to call slaughtering unthreatening Japanese mass murder.

People, particularly Americans, have offered many justifications and excuses for Trumans mass slaughter. That it was necessary to end the war. That it was necessary to save tens of thousands, even hundreds of thousands of American lives. But as Truman at the time knew, and as his advisers, including his military advisers, told him prior to the bombing of Hiroshima, none of these was true.

Truman, in his press release informing the American people about the annihilation of Hiroshima, offered the primitive logic of retribution: The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid many fold. Even this best face does not change what Truman did.

What if Adolf Hitler had dropped a nuclear bomb on a British or American city? What if during the Cuban Missile Crisis Nikita Khrushchev had incinerated Miami? Would we not call such acts mass murder, even though in Hitlers case it would have also been done with the veneer of a rationale that it was a military operation and not the mass slaughter of noncombatants? In the case of Hitler, we would inscribe his act prominently in his long ledger of evil. Why should Trumans wholesale extermination of so many men, women, and children be different?

What if the Japanese had not surrendered a few days after Nagasakis bombing, and Truman had proceeded to annihilate another Japanese city? And then another. And another. And another. At what point would people stop making excuses? At what point would all people speak plainly about his mass murdering? Why would the successive nuclear annihilation of the people of, say, five or ten Japanese cities be deemed mass murderwhich undoubtedly it would bebut the slaughter of the Japanese of only two cities not be?

Or what if the Americans had conquered a few Japanese cities, stopped their advance, and proceeded to shoot 140,000 Japanese civil-ians, men, women, and children (the number who died immediately or from injuries in the next few months from the atomic bombing of Hiroshima), explaining to Japans leaders and its public that only surrender would prevent more mass slaughters? Would Trumans apologists have similarly justified this more conventional mass murdering as militarily and morally necessary? What if three days later Truman ordered American soldiers to shoot another seventy thousand Japanese men, women, and children from a second city? Would we not call such slaughters mass murder? Except for the technological difference between 210,000 bullets and two nuclear bombs (the nuclear bombs destroyed also the cities themselves, and subsequently caused at least another sixty thousand deaths owing to radiation poisoning and other injuries), it is hard to see how, in deciding whether each constitutes mass murder, these two scenarios differ in any conceptually or factually meaningful way. Trumans Chief of Staff William Leahy, a Navy admiral, abhorred using nuclear weapons against the Japanese, and not only because the Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender. Leahy explains: My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make wars in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and childrenbecause that is not war but mass murder.

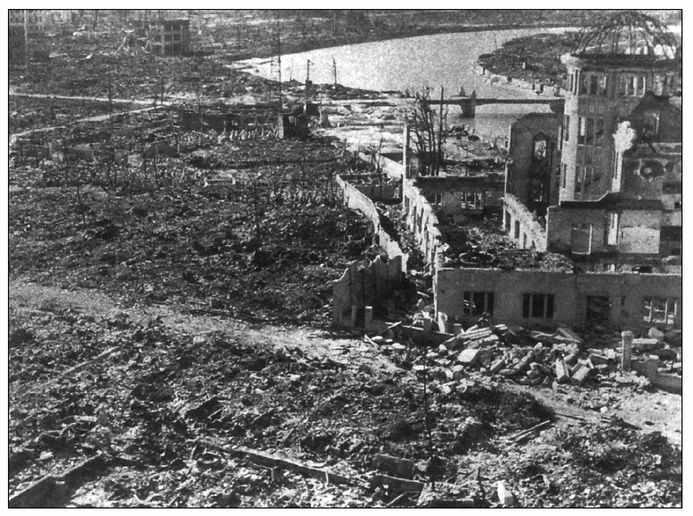

Hiroshima after the mass murder

I start with the Trumans mass annihilation of Japanese to indicate how deficient our understanding of large-scale mass murder is. The willful slaughter of more than a quarter million people, in full view of the world, should be universally recognized for what it was, causing the label mass murderer to be affixed to Trumans name. Japanese, to a degree people in other countries, and especially critics of the United States do see Trumans use of nuclear weapons this way. But in the United States and the corridors of power, it is denied or ignored. That Trumans nuclear incineration of Hiroshima and Nagasakis people is not invariably and prominently listed among our times mass murders points us to one of the acute problemsaside from truthfulnessconfounding our understanding: the problem of definition. How should we define mass murder so that we do not misconstrue it?

Why have Trumans actions not been universally seen and condemned for what they were? For Americans the problem of facing up to the crimes of ones own country and countrymen is real. Most peoples have prettified self-images that cover up blemishes, airbrush scars and open sores on the self-drawn portraits of their nations, their pasts, and themselves. For Americans, Turks, Japanese, Poles, Russians, Chinese, French, British, Guatemalans, Croats, Serbs, Hutu, and countless others, the ugliness that they easily see in others, they fail to acknowledge in themselves, their own countries, or their countrymen. How can we establish appropriate general criteria that give people a more accurate view of themselves?