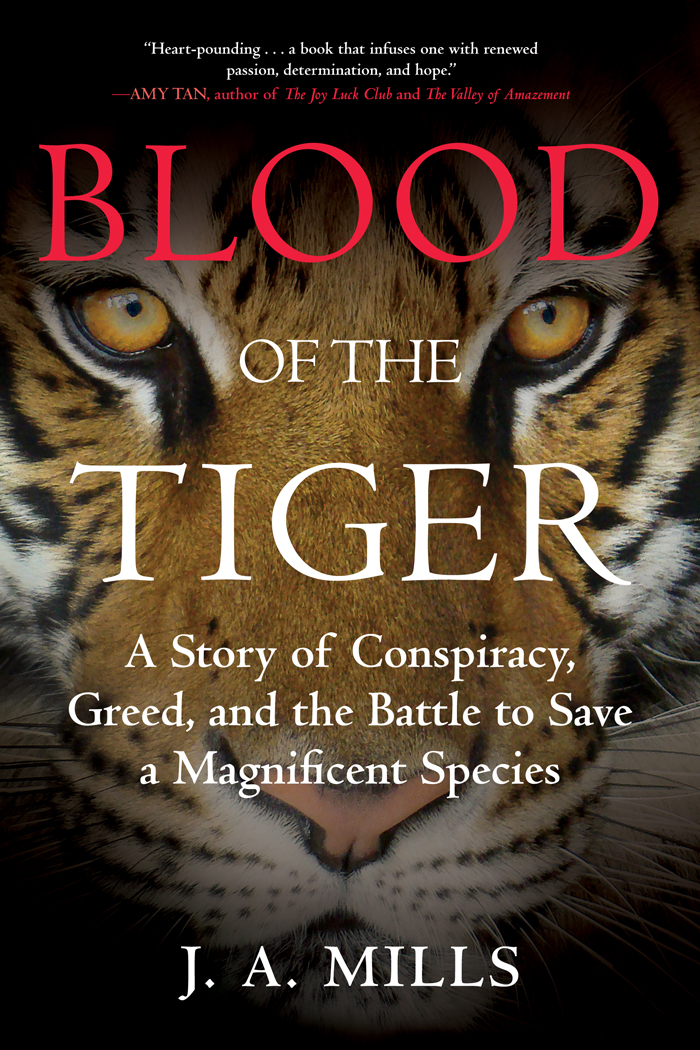

BLOOD OF THE TIGER

A Story of Conspiracy, Greed, and the Battle to Save a Magnificent Species

J.A. MILLS

BEACON PRESS, BOSTON

Beacon Press

Boston, Massachusetts

www.beacon.org

Beacon Press books are published under the auspices of the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations.

2015 by J. A. Mills

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

18 17 16 15 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Text design by Wilsted & Taylor Publishing Services

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mills, Judy A., author.

Blood of the tiger : a story of conspiracy, greed, and the battle to save a magnificent species / J.A. Mills.

pages cm

Provided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8070-7496-1 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-8070-7497-8 (ebook)

1. Tiger tradeChina. I. Title.

SK593.T54M55 2015

639.97'9756dc23

2014015760

For tigers,

the Croc Farm bear,

and Mingma Norbu Sherpa,

who died in service to wildness

The most alive is the wildest.

Not yet subdued to man,

its presence refreshes him.

HENRY DAVID THOREAU, WALKING

He who rides the tiger

is afraid to dismount.

CHINESE PROVERB

CONTENTS

5. INTERMISSION I

The Wild Ones

10. INTERMISSION II

In the Valley of the Shadow

1

THE THRALL OF THE WILD

For fifty-seven years after the Crown of the Continent became Montanas Glacier National Park, there was not a single documented case of a grizzly killing a human. Then, between midnight and dawn on August 13, 1967, two grizzlies killed two nineteen-year-old women at two different backcountry campsites nine mountainous miles apart.

While nestled in for my first-ever overnight in the backcountry, deep within Canadas side of what is now Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park, I was gripped by the details of that gruesome night, as chronicled by Jack Olson in Night of the Grizzlies. In a small orange tent, inside my blue sleeping bag with a red down jacket rolled under my head, I shined the flashlight in my right hand on the paperback in my left. I joked with my wilderness-savvy boyfriend Larry Slonaker about feeling like we were in that Far Side cartoon in which two bears behind trees peer at three people in sleeping bags and declare, Sandwiches!

Are you sure we wont become bear sandwiches tonight? I said, flashing a smile I didnt feel.

Youll be fine, Larry said, kissing my forehead as if I were a child afraid of ghosts.

I read on.

You know, I really am worried about becoming a bear sandwich.

Larry didnt respond. He didnt hear my fear unfurl because he had floated serenely into his dreams.

What haunted me most about Olsons account was Julie Helgesons cry for her mother, who was hundreds of impossible miles away when a grizzly pulled the slim Minnesota coed from the warmth of her sleeping bag into the chilly blackness below the towering spires of the Continental Divide. And how another grizzly, nine miles across the parks astonishing vertical contours, dragged away delicate California beauty Michele Koons from a circle of campers bedded down beside an alpine lakeshore.

Larry and I had camped just above six thousand feet, four and a half miles up a steep, rocky path from a trailhead on a narrow strip of Waterton Lakes long, mountain-rimmed shoreline accessible only by boat. Our tent was thirty paces from a trail that was little more than a ledge that clawed its way along a cliff face and into a round of turquoise water cupped by soaring rock. How apt its called Crypt Lake, I thought. If a grizzly did attack us, no one would hear our cries. And we had no means to call in help.

I lay awake all night, straining to listen and imagining in detail. Was that a bear? Was THAT? I tried to grasp how alone those young women must have felt as they were pulled over plants, rocks, and fallen trees in the death clamp of creatures they could barely see. What was it like for them? What was it really like?

Halfway to dawn, I could no longer ignore my nagging bladder. But my mind saw the menace in wait. His dished forehead above close-set dark eyes, his humped back, his shimmering silver-tipped fur. His long snout with yellow fangs set in a steel-trap jaw. If I stepped outside to relieve my growing discomfort, he would surely carry me off by my bare bottom, ankles tangled in jeans. Then again, what defense was a bubble of orange nylon against four-inch switchblade claws? I had never spent a longer night or known such unremitting fear.

I rejoiced at first light and made my loo just inches from the back of the tent. Immediately after our breakfast of instant coffee and oatmeal, we packed up and I led a speed-trudge down miles of switchbacks. Larry tried to calm me with facts. The main causes of death in Glacier were drowning, heart attack, car accidents, and falling from high places. Did I know I was exponentially more likely to get hit by lightning than mauled by a grizzly?

Cmon, Heart, he said, were going to be fine.

Yes, he called me Heart. And wrote me love poems. As assistant city editor at the newspaper where I worked in Washington State, he massaged my stories from the cop beat into better reads. But I didnt think he could knock out a grizzly.

After a three-hour forced march, accompanied by an unbroken stream of my anxious babbling, off-key singing, and clapping of hands to scare off bears, we reached the trailhead. I plopped down, backpack still affixed, at the far end of the dock to await the water taxi that would motor us back to the tourist bustle of Waterton Township.

As it turned out, safe ground was far less transcendent than I had so desperately anticipated. Instead of feeling heady with relief when we checked into the storied Prince of Wales Hotel on its panoramic bluff above the lake, I felt deflated. Let down. Less alive. Something wondrous had gone missing. I thought it was the vertiginous dazzle of Glaciers backcountry. But it wasnt.

Shortly after I started a new job at another daily newspaper, a large male grizzly entered a campground near Yellowstone National Park on a moonlit summer night, tore open a tent with two Wisconsin men inside, yanked one out, and dragged him into the woods. When rescuers found twenty-three-year-old Roger May an hour later, he was dead and missing some seventy pounds of flesh and blood. I begged my editors to dispatch me to write about killer bears.

As I neared the site of the attack in my burgundy Honda Civic, I began to feel what had slipped my grasp after escaping my imagined Night of the Grizzlies near Crypt Lake. I call it the Man-Eater Effect.

It wasnt the threat of being eaten alive that energized me. It was the firing on all primal cylinders to avoid being eaten. Cylinders most of us rarely, if ever, activate. The primordial cocktail of chemicals that floods the human brain on alert for man-eaters brings a person sublimely, electrically, and wholly to life. Every detail of every second becomes acutely vivid. The color of wildflowers and whether any favored by man-eaters have been nibbled. A slight movement on a hillside. A muddy spot that could have registered a massive paw passing by. An abrupt change in birdsong or the flick of a deers ears that could signal alarm. The snap of a twig in forest shadows.

This heightened state was better than the morphine bliss that once made me sit up on a gurney leaving an operating room and ask, Can we do that again? Its the full-on mindful state our brains were wired for, before guns and wheels gave us dominion over all other creatures and the leisure to let our most arousing instincts atrophy. There are modern-day facsimiles. Like the opiates our brains generate when we fall in love, exercise into a runners high, parachute out of perfectly good airplanes, reach orgasm, or eat dark chocolate. The Man-Eater Effect is more akin to the high that compels war veterans to seek repeated stints in combat. Theres just no brain chemistry like that triggered by the possibility of becoming prey.