For Alice

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

This is not the next great book on American cities. That book is not needed. An intellectual revolution is no longer necessary. What characterizes the discussion on cities these days is not a wrongheadedness or a lack of awareness about what needs to be done, but rather a complete disconnect between that awareness and the actions of those responsible for the physical form of our communities.

Weve known for three decades how to make livable citiesafter forgetting for fouryet weve somehow not been able to pull it off. Jane Jacobs, who wrote in 1960, won over the planners by 1980. But the planners have yet to win over the city.

Certain large cities, yes. If you make your home in New York, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, Portland, or in a handful of other special places, you can have some confidence that things are on the right track. But these locations are the exceptions. In the small and midsized cities where most Americans spend their lives, the daily decisions of local officials are still, more often than not, making their lives worse. This is not bad planning but the absence of planning, or rather, decision-making disconnected from planning. The planners were so wrong for so many years that now that they are mostly right, they are mostly ignored.

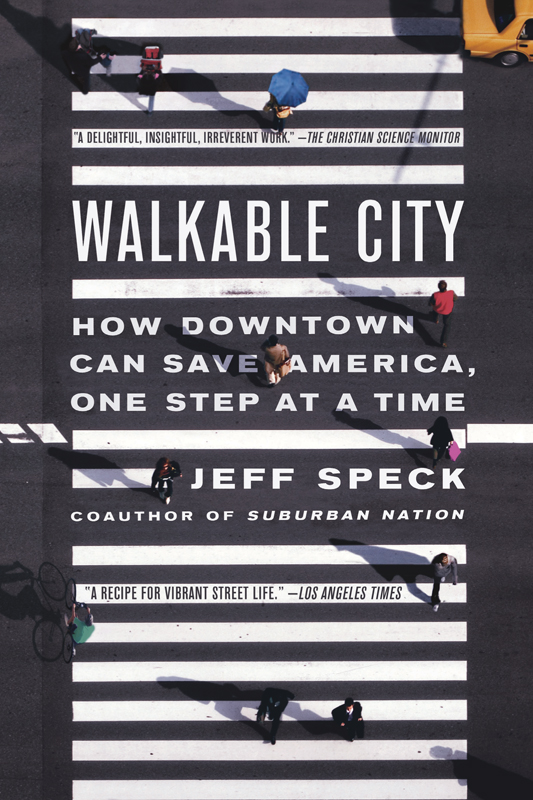

But this book is not about the planning profession, nor is it an argument for more planning per se. Instead, it is an attempt to simply delineate what is wrong with most American cities and how to fix it. This book is not about why cities work or how cities work, but about what works in cities. And what works best in the best cities is walkability.

Walkability is both an end and a means, as well as a measure. While the physical and social rewards of walking are many, walkability is perhaps most useful as it contributes to urban vitality and most meaningful as an indicator of that vitality. After several decades spent redesigning pieces of cities, trying to make them more livable and more successful, I have watched my focus narrow to this topic as the one issue that seems to both influence and embody most of the others. Get walkability right and so much of the rest will follow.

This discussion is necessary because, since midcentury, whether intentionally or by accident, most American cities have effectively become no-walking zones. In the absence of any larger vision or mandate, city engineersworshiping the twin gods of Smooth Traffic and Ample Parkinghave turned our downtowns into places that are easy to get to but not worth arriving at. Outdated zoning and building codes, often imported from the suburbs, have matched the uninviting streetscape with equally antisocial private buildings, completing a public realm that is unsafe, uncomfortable, and just plain boring. As growing numbers of Americans opt for more urban lifestyles, they are often met with city centers that dont welcome their return. As a result, a small number of forward-thinking cities are gobbling up the lions share of post-teen suburbanites and empty nesters with the wherewithal to live wherever they want, while most midsized American cities go hungry.

How can Providence, Grand Rapids, and Tacoma compete with Boston, Chicago, and Portland? Or, more realistically, how can these typical cities provide their citizens a quality of life that makes them want to stay? While there are many answers to that question, perhaps none has been so thoroughly neglected as design, and how a comprehensive collection of simple design fixes can reverse decades of counterproductive policies and practices and usher in a new era of street life in America.

These fixes simply give pedestrians a fighting chance, while also embracing bikes, enhancing transit, and making downtown living attractive to a broader range of people. Most are not expensivesome require little more than yellow paint. Each one individually makes a difference; collectively, they can transform a city and the lives of its residents.

Even New York and San Francisco still get some things wrong, but they will continue to poach the countrys best and brightest unless our other, more normal cities can learn from their successes while avoiding their mistakes. We planners are counting on these typical places, because America will be finally ushered into the urban century not by its few exceptions, but by a collective movement among its everyday cities to do once again what cities do best, which is to bring people togetheron foot.

A GENERAL THEORY OF WALKABILITY

As a city planner, I make plans for new places and I make plans for making old places better. Since the late eighties, I have worked on about seventy-five plans for cities, towns, and villages, new and old. About a third of these have been built or are well under way, which sounds pretty bad, but is actually a decent batting average in this game. This means that I have had my fair share of pleasant surprises as well as many opportunities to learn from my mistakes.

In the middle of this work, I took four years off to lead the design division at the National Endowment for the Arts. In this job, I helped run a program called the Mayors Institute on City Design, which puts city leaders together with designers for intensive planning sessions. Every two months, somewhere in the United States, we would gather eight mayors and eight designers, lock ourselves in a room for two days, and try to solve each mayors most pressing city-planning challenge. As might be imagined, working side by side with a couple hundred mayors, one mayor at a time, proved a greater design education than anything I have done before or since.

I specialize in downtowns, and when I am hired to make a downtown plan, I like to move there with my family, preferably for at least a month. There are many reasons to move to a city while you plan it. First, its more efficient in terms of travel and setting up meetings, something that can become very expensive. Second, it allows you to truly get to know a place, to memorize every building, street, and block. It also gives you the chance to get familiar with the locals over coffee, dinners in peoples homes, drinks in neighborhood pubs, and during chance encounters on the street. These nonmeeting meetings are when most of the real intelligence gets collected.

These are all great reasons. But the main reason to spend time in a city is to live the life of a citizen. Shuttling between a hotel and a meeting facility is not what citizens do. They take their kids to school, drop by the dry cleaners, make their way to work, step out for lunch, hit the gym or pick up some groceries, get themselves home, and consider an evening stroll or an after-dinner beer. Friends from out of town drop in on the weekend and get taken out for a night on the main square. These are among the many normal things that nonplanners do, and I try to do them, too.

A couple of years ago, while I was working on a plan for Lowell, Massachusetts, some old high-school friends joined us for dinner on Merrimack Street, the heart of a lovely nineteenth-century downtown. Our group consisted of four adults, one toddler in a stroller, and my wifes very pregnant belly. Across the street from our restaurant, we waited for the light to change, lost in conversation. Maybe a minute passed before we saw the pushbutton signal request. So we pushed it. The conversation advanced for another minute or so. Finally, we gave up and jaywalked. About the same time, a car careened around the corner at perhaps forty-five miles per hour, on a street that had been widened to ease traffic.