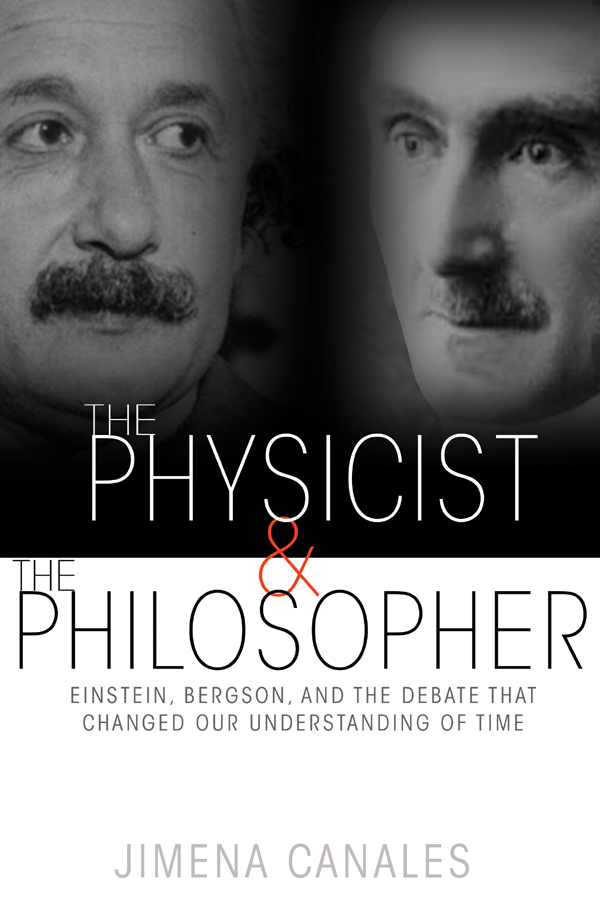

THE PHYSICIST AND THE PHILOSOPHER

THE PHYSICIST & THE PHILOSOPHER

EINSTEIN, BERGSON, AND THE DEBATE THAT

CHANGED OUR UNDERSTANDING OF TIME

JIMENA CANALES

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2015 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket photographs: Albert Einstein, detail from photograph of Albert Einstein and Others, 1931. Courtesy of the Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology, Smithsonian Institution Libraries. Henri Bergson, from The Outline of Science: A Plain Story Simply Told, by J. Arthur Thomson, 1922.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Canales, Jimena, author.

The physicist and the philosopher : Einstein, Bergson, and the debate that changed our understanding of time / Jimena Canales.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-16534-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. TimePhilosophy.

2. Relativity (Physics) 3. Einstein, Albert, 18791955. 4. Bergson, Henri, 18591941.

5. PhysicistsUnited StatesBiography. 6. PhilosophersFranceBiography. I. Title. BD638.C326 2015 115dc23

2014047686

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon Next LT Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

PREFACE

I cannot get it into my head, wrote Einstein, that the last thirty years make up almost 109 seconds. What makes a moment meaningful, haunting our past and our future? April 6, 1922 was a significant date for Einstein; it was the day he met Henri Bergson, one of the most respected philosophers of his era.

In a widely publicized meeting in Paris, the philosopher congratulated the physicist for having discovered a stunning theory but chastised him for having lost aspects of time that were intuitively important for us. Appalled to see a theory ignore what attracted our attention toward certain events and not to others, Einsteins critic sketched out the principles of an alternative cosmology that would neither fall prey to the arid precision of the sciences nor wallow in poetic rhetoric. Applauded for his full-blooded notion of time, his objections would inspire generations to come.

During the face-to-face encounter between the greatest philosopher and the greatest physicist of the twentieth century, his audience learned how to become more Einsteinian than Einstein. Bergson did not contest any experimental results; he accused the physicist of grafting upon science a dangerous metaphysics. The physicist responded swiftly, enlisting allies against the man who refused to grant to scienceand physicsthe power to reveal the time of the universe.

The time of the universe discovered by Einstein and the time of our lives associated with Bergson spiraled down dangerously conflicting paths, splitting the century into two cultures and pitting scientists against humanists, expert knowledge against lay wisdom. With repercussions for American pragmatism, logical positivism, phenomenology, and quantum mechanics, a series of intrigues and alliances explain why longstanding rivalries between science and philosophy, physics and metaphysics, objectivity and subjectivity are still so passionately fought. By the end of their lives, Bergson reconsidered Einstein and Einstein reconsidered Bergson, but their views remained irreconcilable.

The Physicist and the Philosopher is divided into four main parts. The first opens with three chapters that take us directly to the meeting between Einstein and Bergson. then focuses on the men. It details the various contexts where Einsteins contributions were considered in direct relation to Bergsons critique. We follow the debate as it reverberated from France to England, Germany, and America. In each of these places, we meet some of the major players involved in the conflict, such as the Catholic Church, and see how it affected various scientific and philosophical movements, such as American pragmatism, logical positivism, and quantum mechanics. Some of these chapters focus on key moments before and after April 6, 1922, when similar arguments to those delivered that day were advanced.

centers on the things. It investigates why Einstein and Bergson remained so divided by zooming into particular examples that came up again and againexplicitly and repeatedlyin their discussions and those of their interlocutors. Certain things, such as the telegraph, telephone, radio, film, and automatic registering devices, played salient roles. Microscopic particles, tiny microbes, immense observers, superfast beings, animals and ghosts entered their discussions as well.

concludes with wordsthe last comments they made about each other. At that time, Bergson was nearly eighty, witnessing the rise of Nazism in Germany, the occupation of Paris, and a new era of conflict and unrest. Einstein was well into his seventies. He had retired from the Institute of Advanced Studies in Princeton and was reminiscing about Bergson a few months before the Americans detonated the worlds first hydrogen bomb. In the end, we encounter a story of the rise of science in a divided century, of misunderstanding and mistrust, and of the every day things that tear us apart.

PART 1

THE DEBATE

CHAPTER 1

Untimely

On April 6, 1922, Einstein met a man he would never forget. He was one of the most celebrated philosophers of the century, widely known for espousing a theory of time that explained what clocks did not: memories, premonitions, expectations and anticipations. Thanks to him, we now know that to act on the future one needs to start by changing the past.

Why does one thing did not always lead to the next? The meeting had been planned as a cordial and scholarly event. It was anything but that. The physicist and the philosopher clashed, each defending opposing, even irreconcilable, ways of understanding time. At the Socit franaise de philosophieone of the most venerable institutions in Francethey confronted each other under the eyes of a select group of intellectuals. The dialogue between the greatest philosopher and the greatest physicist of the 20th century was dutifully written down. It was a script fit for the theater. The meeting, and the words they uttered, would be discussed for the rest of the century.

The philosophers name was Henri Bergson. In the early decades of the century, his fame, prestige, and influence surpassed that of the physicistwho, in contrast, is so well known today. Bergsons reputation was at risk after he confronted the younger man. But so was Einsteins. The criticisms leveled against the physicist were immediately damaging. When the Nobel Prize was awarded to Einstein a few months later, it was not given for the theory that had made the physicist famous: relativity. Instead, it was given for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effectan area of science that hardly jolted the publics imagination to the degree that relativity did. The reasons behind the decision to focus on work other than relativity were directly traced to what Bergson said that day in Paris.

The president of the Nobel Committee explained that although most discussion centers on his theory of relativity, it did not merit the prize. Why not? The reasons were surely varied and complex, but the culprit mentioned that evening was clear: It will be no secret that the famous philosopher Bergson in Paris has challenged this theory. Bergson had shown that relativity pertains to epistemology rather than to physicsand so it has therefore been the subject of lively debate in philosophical circles.

Next page