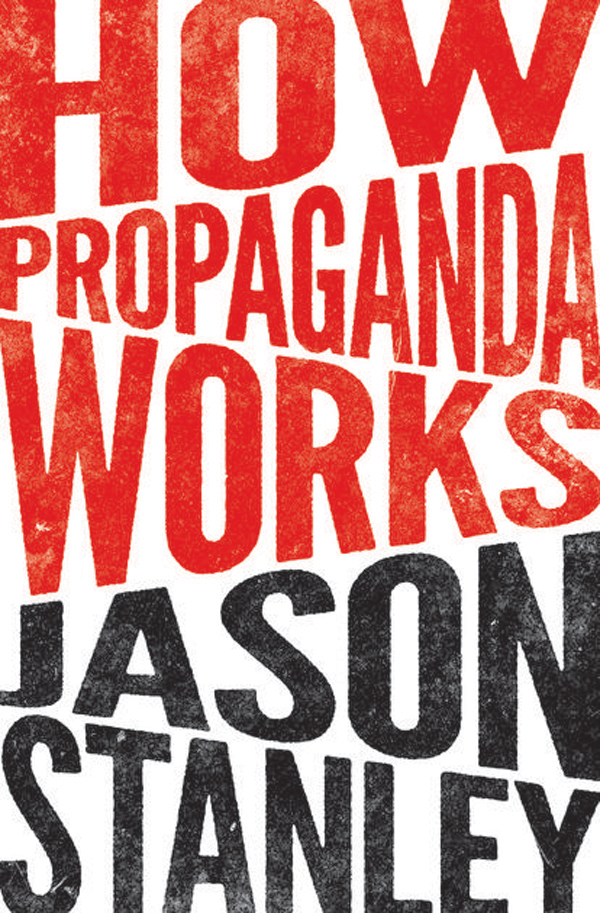

HOW PROPAGANDA WORKS

HOW

PROPAGANDA

WORKS

JASON STANLEY

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton & Oxford

Copyright 2015 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket design by Chris Ferrante

Excerpts from Victor Kemperer, The Language of the Third

Reich: LTI, Lingua Tertii Imperii, translated by Martin Brady

Reclam Verlag Leipzig, 1975. Used by permission of

Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury

Publishing PLC.

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 9780691164427

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014955002

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon Next LT Pro and League Gothic

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This will always remain one of the best jokes of democracy, that it gave its deadly enemies the means by which it was destroyed.

JOSEPH GOEBBELS, REICH MINISTER OF PROPAGANDA, 193345

CONTENTS

PREFACE

In August 2013, after almost a decade of teaching at Rutgers University and living in apartments in New York City, my wife Njeri Thande and I moved to a large house in New Haven, Connecticut, to take up positions at Yale University. Along with the move in academic affiliations came space. Soon thereafter, my stepmother, Mary Stanley, called me with a request. Could she send me some boxes of books from my fathers library? The request filled me with fear as well as anticipation. I spent half my childhood in the house she shared with my father. The walls of every room were filled with books. The shelves were double stacked; behind each row of books was another. Only my father knew the complex code that unlocked the mystery of its organizational system, and he had passed away in 2004. Mary told me that she would be sending me the contents of a room or two, to clear out a little bit of space in the house. Who knew what we would receive? With trepidation, we agreed.

My father Manfred Stanley was a sociology professor at Syracuse University, where he was for many years the director of the Center for the Study of Citizenship at the Maxwell School for Citizenship and Public Affairs; Mary Stanley was also a professor at Syracuse, and his colleague and coconspirator in the Center. He began his career as an Africanist, with a

My father, like my mother Sara Stanley, was a survivor of the Holocaust. No doubt as a consequence, he devoted his academic career to a theoretical repudiation of authoritarianism in all of its various guises. He argues in his work that no system that usurps the autonomy of persons can be acceptable, even if it is in the name of greater social efficiency or the common good. The lessons of history show that humans are too prone to confuse the furtherance of their own interests with the common good, and their subjective explanatory framework with objective fact.

I owe a substantive intellectual debt to my father and my stepmother Mary. Their project on democratic citizenship has shaped and molded my own. One way of seeing my fathers work is as devoted to explaining how sincere, well-meaning people can be deceived by self-interest into unwittingly producing propaganda. My goal in this book is to explain how sincere, well-meaning people, under the grips of flawed ideology, can unknowingly produce and consume propaganda. In the service of acknowledging my debt, I will explain the central themes of his written work, and their joint project, as a preface to my project in this book.

My fathers dissertation concerns the destructive effects of British colonialism on the Gikuyu. Its focus is on the Gikuyu land tenure system, a manner of managing land so central to Gikuyu identity that, as Jomo Kenyatta writes, [i]n studying the Gikuyu tribal organization it is necessary to take into consideration land tenure as the most important factor in the social, political, religious, and economic life of the tribe. The Gikuyu land tenure system was radically different from the system of private property at the basis of British society; it was a mans pride to own a property and his enjoyment to allow collective use of such property.the British belief that their particular system of private property was universal led to unbridgeable misunderstandings between even well-intentioned British colonialists and the Gikuyu people. The moral of colonialism is that it is much harder to make objective decisions on behalf of others even for the sake of their own good. Even those British colonialists who were sincere and well meaning found it impossible to distinguish between genuinely liberal values, their own local cultural practices, and naked self-interest.

My fathers view of autonomy was richer than mere non-domination by others. His worldview required every citizen to be provided with a liberal education, the goal of which would be to foster the capacity for autonomous decision making about ones life plans, where this involved the kind of reflection that, for him, allowed for genuine autonomy. The description of the contours of an education that could play this democratic role takes up another portion of his academic writings.

The target of my fathers book is what he often called technicism the view that scientific expertise and technological advancements are the solution to the problems of the human condition. My father saw two chief dangers in the technicist worldview. First, it seeks to replace a liberal education with vocational technical skills. The technicist educational system therefore seeks to rob us of the capacity for autonomy. Secondly, a technicist culture encourages a tendency to defer ones practical decisions to the epistemic authority of experts. As he writes,

Some societies are organized so as to restrict the distribution of important forms of authoritative agency to particular ruling elites. In other societies all normal members of society are considered responsible free agents. Even in most of these, however, certain people are designated as more equal than others. Why? Because their mastery of a particular cognitive area of discourse or practice seems to make it socially desirable that they be granted the right,

Of course, modernity demands trusting professionals; we must, after all, see the doctor. There are also salient cases in which distrust of experts is key to propaganda; the case of climate change denial is the salient example (though, even here, the form of the distrust has taken the shape of the mobilization of an alternative domain of pseudoexperts, such as the junk science commentators discussed in this book). Nevertheless, history shows that even the well meaning are likely to conflate the products of genuine scientific expertise with the imposition of their own subjective values. The British imposed their own conception of private property onto the Gikuyu inhabitants of the land they had occupied, under the misguided belief that their system of property rights was part of universally valid economic theory. The British mistakenly saw their system of private property as part of the universal values liberalism should spread. He saw similar forces at work in the United States, in the education system and the mass media.

My father does not solve the difficult problem of distinguishing legitimate versus illegitimate deference to experts, of drawing on knowledge without being subordinate to it. But he is clear about the dangers of technicist culture. Even if statistics are accurate, they nevertheless can serve a propagandistic role in domination and oppression, by obscuring the narratives that would explain them. This is a use of the ideals of scientific objectivity and the common good in pursuit of social control.

Next page