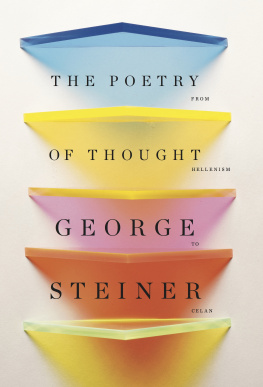

GEORGE STEINER

AT

THE NEW YORKER

Edited and with an Introduction by Robert Boyers

A NEW DIRECTIONS BOOK

CONTENTS

I. HISTORY & POLITICS

II. WRITERS AND WRITING

III. THINKERS

IV. LIFE STUDIES

IN MEMORY OF MR. SHAWN

AN INTRODUCTION BY ROBERT BOYERS

BETWEEN 1967 AND 1997, George Steiner wrote forThe New Yorker more than one hundred and fifty pieces. Most of themwere reviews, or review-essays, many quite lengthy by the standards of a weeklymagazine. Often in the course of his tenure at The New Yorker Steinerwas said to be the ideal successor to Edmund Wilson, who, like Steiner, hadwritten over several decades on a great range of issues and had made new booksand old, difficult ideas and unfamiliar subjects, seem compelling not only toliterary intellectuals but to what was once called the general reader.

In the years when he wrote regularly for The New YorkerSteiner contributed often to other publications as well, collecting only a smallproportion of his reviews in miscellaneous volumes like Language andSilence, On Difficultly, and Extraterritorial. Remarkably,Steiner also wrote several important academic books during this period,including major works like After Babel and Antigones. Thoughhe was sometimes attacked for spreading himself too thin and taking on subjectsbeyond his own field of comparative literature, his books were more oftenpraised in the highest terms by writers like Anthony Burgess and John Banville,and by leading scholars in several disciplines, from Bernard Knox and Terrencedes Pres to Donald Davie, from Stephen Greenblan to Edward Said and John Bayley.Said regarded him as an exemplary and properly passionate guide to much of thebest in contemporary writing and ideas, and Susan Sontag praised his generosityand his willingness to provoke, even when he knew that he would be attackedfor his views. He thinks, Sontag noted in 1980, that there are great works ofart that are clearly superior to anything else in their various forms, thatthere is such a thing as profound seriousness. And works created out of profoundseriousness have in his view a claim on our attention and our loyalty thatsurpasses qualitatively and quantitatively any claim made by any other form ofart or entertainment. While there were those, in the American academyespecially, who were all too ready to reach for the dismissive adjectiveelitist to describe such a stance, Sontag was more than willing to associateherself with Steiners commitment to seriousness, and there were tens ofthousands of New Yorker readers who were likewise grateful for themodel of lucidity, learning, and intellectual independence exemplified bySteiner.

It is notoriously difficult to make a strong case for the enduringvitality of criticism written for a weekly or monthly magazine. We go back tothe miscellaneous collections of pieces by Edmund Wilson, or Lionel Trilling, orSteiners long-time colleague at The New Yorker, John Updike, and ofcourse we find, among other things, a variety of local insights or judgmentsthat may seem to us, and often are, ephemeral. Can it matter to us now that JohnBergers novel G be read as an imaginative gloss on Kierkegaardsreading of Mozarts Don Giovanni in Either/Or, as Steinerrecommended back in 1973? Is it important to note, with Trilling, that certainwritersHemingway is a prime examplebecome fatuous or maudlin only when theyare writing in the first person?

But then all worthwhile insights are at bottom local, or are foundedon close readings of texts, sentences, loosely or tightly formulated ideas.Trillings view of authenticity is compelling to us because it is made to emergefrom his deep absorption in particular works by Hegel, Diderot, Wilde andothers. Wilsons understanding of violence in his account of Bolshevism haseverything to do with his careful attention to relevant texts, speeches andincidents, many of which may not in themselves seem to us terriblyconsequential. When Steiner writes of Bergers novel G, he understandsthat, as a highly literaryindeed preciousaffair, the novel asks to be readwith an eye to its plainly recognizable literary origins. To speak ofSteiners observations in such a reading as local is to say in fact only thathe was willing to do the essential work of the critic acutely responsive to anovel he took to have some genuine value.

Of course it is no small matter that Steiner is a fabulously learnedreader, that he is fluent in several languages and can speak as comfortablyabout Plato and Heidegger and Simone Weil as he can about Fernando Pessoa andAleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Leading Russian scholars acknowledged, when Steinersearly book, Tolstoy or Dostoyevski, appeared in 1959, that his grasp ofthe relevant texts and contexts was impressive, and that even without aknowledge of Russian, Steiner generated enormously original insights stirringeven to specialists in Slavic literature. That has been the case as well withSteiners work in other areas often thought to be the exclusive precinct ofclassicists, or philosophers, or linguists. And so it is not surprising that, inhis essays and reviews, Steiner has seemed an ideal guide to a great manysubjects, from the Risorgimento in Italy to the literature of the gulag, fromthe history of chess to the enduring importance of George Orwell or the idiom ofprivacy in nineteenth-century fiction.

When he confronts the work of a canonical modern figureBrecht, forexample, or Celine, or Thomas MannSteiner takes very little as settled orbeyond dispute. He proceeds from the assumption that a case remains to be made,and that even with a fiercely original writer, context counts for a great deal,and is apt to be considerably more elusive than is often acknowledged. Brecht,Steiner believes, requires to be placed, exactly, with respect to a variety ofpredecessor figures, including Lessing and Schiller, and in so placing him,Steiner reminds us that, like them, Brecht sets out to be a teacher, a moralpreceptor, in ways that become palpable to us as the plays and poems are deftlyscanned. Equally illuminating is Steiners way of positioning his man within theessential political, ethical and religious framework. Readers of The NewYorker could thus expect from Steiner, on a regular basis, passagesastonishing for their vividness and economy, and deeply instructive in theirmastery of an emotional and ideological terrain out of reach of virtually anyother practicing critic. Brechts detestation of bourgeois capitalism, Steinerwrote,

remained visceral, his intimations of its impending doom ascheerily anarchic as ever. But much in this prophetic loathing, in both itspsychology and its means of articulation, harks back to the bohemiannose-thumbing of his youth and to a kind of Lutheran moralism. His acuteantennae told him of the stench of bureaucracy, of the gray petit-bourgeoiscoercions that prevailed in Mother Russia. Even as Martin Heidegger was duringthis same time developing an inward, private National Socialism (theexpression comes from an S.S. file), so Brecht was expounding for and to himselfa satiric, analytic Communism alien to Stalinist orthodoxy and also to thesimplistic needs of the proletariat and the left intelligentsia in the West.

The palpable features of the passage on Brecht include, mostobviously, the range and depth of learning, the pedagogic clarity, the movementthrough ideas without any trace of heavy breathing or insistence. This, we feel,is criticism as the formal discourse of an amateur, as R. P. Blackmur once putit, with the word amateur signifying a person who is interested in manythings, speaks for himself rather than for a school or an entrenchedtheoretical position, and doesnt at all mind owning up to an enthusiasm or anaversion. But there is also, in the passage on Brecht, as in hundreds of othersI might have selected, an extraordinary speed and fluency, an ability to invokean origin or an intellectual nexus briefly, but with no trace of superficialityor special pleading. When Steiner notes the bohemian nose-thumbing of Brecht,his gift for satire and his visceral antagonism to orthodoxy, he perfectlyaccounts for the peculiar nature of Brechts Communism, regarding it as anexpression of the mans recoil from the stench of bureaucracy and the graypetit-bourgeois coercions. We understand at once, in Steiners passage, whyStalinist Russia could not be for Brecht an attractive alternative to thecapitalist societies he routinely disparaged. And we understand, too, why EdwardSaid was struck, as he said, with the energy and, at its best, the relentlessconcentration of [Steiners] thought. Those features are everywhere present inthis volume of criticism drawn from the pages of the