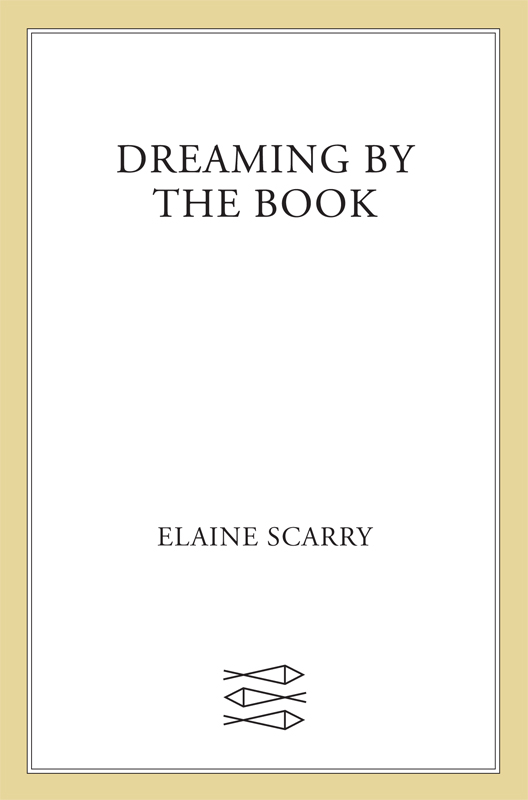

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

7:

8:

9:

10:

11:

12:

for Jack Davis

PART ONE

Making Pictures

On Vivacity

When we speak in everyday conversation about the imagination, we often attribute to it powers that are greater than ordinary sensation. But when we are asked to perform the concrete experiment of comparing an imagined object with a perceptual onethat is, of actually stopping, closing our eyes, concentrating on the imagined face or the imagined room, then opening our eyes and comparing its attributes to whatever greets us when we return to the sensory worldwe at once reach the opposite conclusion: the imagined object lacks the vitality and vivacity of the perceived one; it is in fact these very attributes of vitality and vivacity that enable us to differentiate the actual world present to our senses from the one that we introduce through the exercise of the imagination. Even if, as Jean-Paul Sartre observed, the object we select to imagine in this experiment is the face of a beloved friend, one we know in intricate detail (as Sartre knew the faces of Annie and Pierre), it will be, by comparison with an actually present face, thin, dry, two-dimensional, and inert.

It seems that we tend to notice the inadequacy of daydreamed faces only when we are especially keen on seeing a specific persons face, only when we desperately care to have it present in the mind with clarity and force. We then notice the deficiency, and, like Prousts Marcel, who berates himself for his inability to picture the face of Albertine or the face of his grandmother, we conclude that the vacuity of our imagining is somehow peculiar to our feeling about this particular person and that there must be a hidden defect in our affection. But the vacuity is instead general, and all that is peculiar or particular to such cases is the intensity of wishing to imagine that makes us confront, with more than usual honesty, the fact that we cannot do so. It is when we are soaked with the longing to imagine that we notice, as John Keats confessed, the fancy cannot cheat so well / As she is famd to do. By means of the vividness of perceptions, we remain at all moments capable of recovering, of recognizing the material world and distinguishing it from our imaginary world, even as we lapse into and out of our gray and ghostly daydreams. Aristotle refers to this grayness as the feebleness of images. Sartre calls it their essential poverty.

Of course, insofar as the imagination is enfeebled and impoverished, it is so only on sensory grounds. To complain that the imagined object lacks vivacity and vitality is only to complain that it is not a perceptual object, since vivacity and vitality are the very heart of perception. We should not be surprised that the sensory realm surpasses the imaginary realm on sensory ground; we should only be surprised that this does not always strike us with the force of tautology. Phrased another way, only by decoupling vividness from the imaginary (where we unreflectingly and inaccurately place it in many everyday conversations about aesthetics) and attaching it to its proper moorings in perception, can we then even recognize, first, that the imagined object is not ordinarily vivid, and second, that its not being vivid is tautologically bound up with its being imaginary.

Now it is a remarkable fact that this ordinary enfeeblement of images has a striking exception in the verbal arts, where images somehow do acquire the vivacity of perceptual objects, and it is the purpose of this book to trace some of the ways this comes about. The verbal arts are of particular concern here because theyunlike painting, music, sculpture, theater, and filmare almost wholly devoid of actual sensory content. There is nothing mysterious about the fact that a painting approximates or exceeds the vivacity of the visible world, since it is itself a piece of the visible world. A painting by Henri Matisse or one of the great Florentine colorists, for example, saturates our eyes with actual sensory experience. The airy yellow and ochre stripes of Interior at Nice Its visual features, as has often been observed, consist of monotonous small black marks on a white page. It has no acoustical features. Its tactile features are limited to the weight of its pages, their smooth surfaces, and their exquisitely thin edges. The attributes it has that are directly apprehensible by perception are, then, meager in number. More important, these attributes are utterly irrelevant, sometimes even antagonistic, to the mental images that a poem or novel seeks to produce (steam rising across a windowpane, the sound of a stone dropped in a pool, the feel of dry August grass underfoot), the ones whose vivacity is under investigation here.

To be clear, it might be useful to distinguish three phenomena. First, immediate sensory content: the light-filled surface of Matisses Interior at Nice, the sweet fleeting notes of Honeysuckle Rose on Fats Wallers piano recording, or indeed the particular room one, at this moment, inhabits while reading. Second, delayed sensory content, or what can be called instructions for the production of actual sensory content. A musical score has no immediate acoustical content, only the immediate visual content of lines and dots and the immediate tactile content of the smooth, thin pages, but it does directly specify a sequence of actions that, if followed, produces actually audible content. The third case, in contra-distinction to the first two, has no actual sensory content, whether immediate or delayed; there is instead only mimetic content, the figural rooms and faces and weather that we mimetically see, touch, and hear, though in no case do we actually do so.

It probably makes sense in this third case, as in the second, to use the word instructions. When we say Emily Bront describes Catherines face, we might also say Bront gives us a set of instructions for how to imagine or construct Catherines face. This reformulation is accurate if cumbersome, in that it shifts the site of mimesis from the object to the mental act. We habitually say of images in novels that they represent or are mimetic of the real world. But the mimesis is perhaps less in them than in our seeing of them. In imagining Catherines face, we perform a mimesis of actually seeing a face; in imagining the sweep of the wind across the moors, we perform a mimesis of actually hearing the wind. Imagining is an act of perceptual mimesis, whether undertaken in our own daydreams or under the instruction of great writers. And the question is: how does it come about that this perceptual mimesis, which when undertaken on ones own is ordinarily feeble and impoverished, when under authorial instruction sometimes closely approximates actual perception? In the poem Birthplace, Seamus Heaney describes a young boy named Seamus Heaney staying up all night to read for the first time a novel (Thomas Hardys Return of the Native ) and at dawn not knowing whether the newborn sounds of bird and rooster and dog were coming to him from the surface of the field or from the surface of the page. The question is: by what miracle is a writer able to incite us to bring forth mental images that resemble in their quality not our own daydreaming but our own (much more freely practiced) perceptual acts?