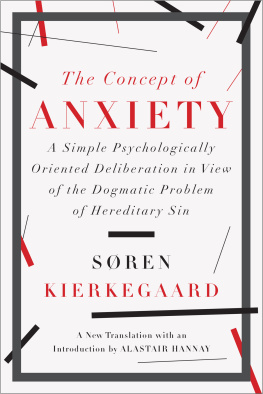

THE CONCEPT OF ANXIETY

KIERKEGAARDS WRITINGS, VIII

THE CONCEPT OF ANXIETY

A SIMPLE PSYCHOLOGICALLY ORIENTING DELIBERATION ON THE DOGMATIC ISSUE OF HEREDITARY SIN

by Sren Kierkegaard

Edited and Translated with Introduction and Notes by

Reidar Thomte

in collaboration with

Albert B. Anderson

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

Copyright 1980 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, Guildford, Surrey

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kierkegaard, Sren, 18131855.

The concept of anxiety.

Translation of Begrebet Angess.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Sin, Original. 2. Psychology, Religious. 3. Anxiety.

I. Thomte, Reidar. II. Anderson, Albert, 1928- III. Title.

BT720.K52 1980 233.14 79-3217

ISBN 0-691-07244-2

ISBN 0-691-02011-6 (pbk.)

Editorial preparation of this work has been assisted by a grant from Lutheran Brotherhood, a fraternal benefit society, with headquarters in Minneapolis, Minnesota

Princeton University Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources

Designed by Frank Mahood

http://pup.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

18 19 20

ISBN-13: 978-0-691-02011-2 (pbk.)

CONTENTS

HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

Among those attending W.F.J. Schellings series of lectures on the philosophy of mythology and revelation (Philosophie der Mythologie und Offenbarung) at the University of Berlin in the winter of 1841-1842 were both Friedrich Engels and Sren Kierkegaard. Each of these studies helped him to shape his own philosophical position and also furnished him with an arsenal for his relentless battle with Hegel and speculative idealism.

Leibnizs review of arguments pertaining to the problem of freedom interested Kierkegaard especially. In response to Leibnizs point in the Theodicy that the connection between Subsequently, Kierkegaard dealt with the problem of freedom in three of his pseudonymous works: Philosophical Fragments defines the ontological ground of freedom and its realm, whereas The Concept of Anxiety and The Sickness unto Death consider the anthropological aspects of freedom.

In response to Descartess idea of freedom, Kierkegaard noted in his papers that: In freedom I can emerge only from that into which I have entered in freedom.... If I am going to emerge from doubt in freedom, I must enter into doubt in freedom. (Act of Will.) Therefore, Descartes, according to Kierkegaard, had inverted the relationship between thought and will:

Incidentally, it is noteworthy that Descartes, who himself in one of the meditations explains the possibility of error by recalling that freedom in man is superior to thought, nevertheless has construed thought, not freedom, as the absolute. Obviously this is the position of the elder Fichtenot cogito ergo sum, but I act ergo sum, for this cogito is something derived or it is identical with I act; either the consciousness of freedom is in the action, and then it should not read cogito ergo sum, or it is the subsequent consciousness.

Kierkegaard criticized the Cartesian principle of methodical doubt because it mistakenly gives more weight to reflection (thought) than it does to act (will).

What skeptics should really be caught in is the ethical. Since Descartes they have all thought that during the period in which they doubted they dared not to express anything definite with regard to knowledge, but on the other hand they dared to act, because in this respect they could be satisfied with probability. What an enormous contradiction! As if it were not far more dreadful to do something about which one is doubtful (thereby incurring responsibility) than to make a statement. Or was it because the ethical is in itself certain? But then there was something which doubt could not reach!

Descartess apparently epistemological problem is for Kierkegaard an existential one; that is, the solution of doubt lies not in reflection but in resolution.

The remainder of Kierkegaards studies during the fall of 1842 centered on Trendelenburg and Tennemann, and from them Kierkegaard gained insights into Aristotles thought. References in his papers indicate that he also made use of primary sources. In a discussion of Aristotles doctrine of motion, Tennemann wrote: Because possibility and actuality are distinguishable in all things, change, insofar as it is change, is the actualization of the possible.... The transition from possibility to actuality is a change, . This could be expressed more precisely by saying: change, motion, is the This conception of change held great significance for Kierkegaard, and he made Tennemanns interpretation of the point of departure for his own theory of transitionwhat in The Concept of Anxiety is referred to as the qualitative leap.

Kierkegaard found support for his conception of the qualitative leap in Trendelenburgs idea that the highest principles can be demonstrated only indirectly (negatively). Yet he reproached Trendelenburg for his failure to recognize the necessity of a qualitative leap in order to recognize the validity of such principles.

Kierkegaards primary criticism of Aristotle centers on his view that the real self resides ultimately in the thinking part of man, and that consequently the contemplative life constitutes mans highest happiness. Kierkegaard found in Aristotle an understanding that ethics will not admit of the precision required for scientific knowledge: The definition of science that Aristotle gives in 6,3 is very important. The objects of science are things that can be only in a single way. What is scientifically knowable is therefore the necessary, the eternal, for everything that is absolutely necessary is also absolutely everlasting. For Kierkegaard, therefore, Aristotle falls short in his understanding that the consummation of mans ethical life lies in the contemplative posture.

Thus, however else Kierkegaard may be classified in the history of thought, he stands in direct opposition to the philosophical idealism of his day.

There is no question but that Kierkegaards thought was influenced by Hegels; however, there is some disagreement as to the degree and nature of that influence. Per Lnning writes:

It has usually been maintained that Hegels philosophy was a decisive influence in the formulation of Kierkegaards thought, especially his conception of history and of the paradox in relation to history.... Such a view seems to be rooted in a complete failure to recognize fully how Kierkegaards interpretation stands entirely independent of the Hegelian philosophy of religion. However, many of Kierkegaards conceptual formulations may be due to a relation to Hegel.

The views of Stephen Crites and Mark Taylor would have Kierkegaard considerably more indebted to Hegel, and as evidence they indicate the similarities between Kierkegaards concept of the self in The Sickness unto Death and a passage in Hegels Phenomenology of Mind.

The Concept of Anxiety was published on June 17, 1844, the year in which Nietzsche was born and Kierkegaard was thirty-one years old. On the same day, Kierkegaard also published a book called

Next page