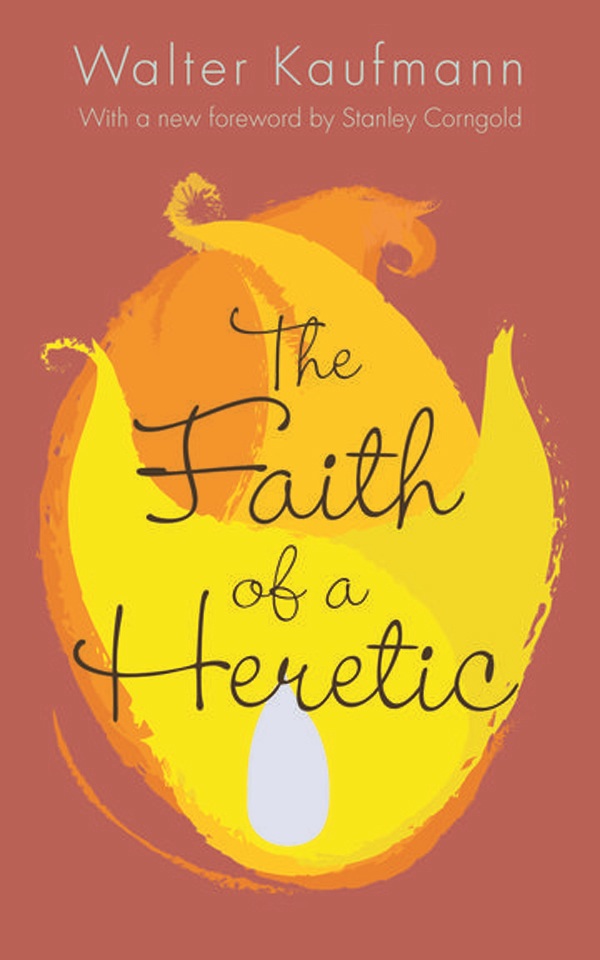

The

Faith

of a

Heretic

The

Faith

of a

Heretic

WALTER KAUFMANN

WITH A NEW FOREWORD BY STANLEY CORNGOLD

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2015 by the Walter Kaufmann Copyright Trust

Foreword copyright 2015 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Original cloth edition published by Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1961

Anchor Books Edition, 1963

First Princeton University Press paperback edition, with a new foreword by Stanley Corngold, 2015

Library of Congress Control Number 2014951277

Paperback ISBN 978-0-691-16548-6

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Janson Text

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To My Uncles

Walter Seligsohn

who volunteered in 1914 and was shot off his horse

on the Russian front in 1915

Julius Seligsohn

AND

Franz Kaufmann

both Oberleutnant, Iron Cross, First Class, 191418,

one a devout Jew,

one a devout convert to Christianity,

one killed in a Nazi concentration camp in 1942,

one shot by the Secret Police in 1944,

both for gallantly helping others

in obedience to conscience, defiant

J EREMIAH: They have healed the wound of my people lightly, saying, Peace, peace, when there is no peace.

K ANT: All the interest of my reason (speculative as well as practical) comes together in the following three questions:

1. What can I know?

2. What ought I to do?

3. What may I hope?

Critique of Pure Reason

W HITMAN: Piety and conformity to them that like,

Peace, obesity, allegiance, to them that like

I am he who walks the States with a barbd tongue, questioning every one I meet,

Who are you that wanted only to be told what you knew before?

Who are you that wanted only a book to join you in

your nonsense?

By Blue Ontarios Shore

N IETZSCHE: Is it really so difficult simply to accept what is considered truth in the circle of ones relatives and of many good men, and what, moreover, really comforts and elevates man? Is that more difficult than to strike new paths, fighting the habitual, experiencing the insecurity of independence and the frequent wavering of ones feelings and even ones conscience, proceeding often without any consolation. Here the ways of men part: if you wish to strive for peace of soul and pleasure, then believe; if you wish to be a devotee of truth, then inquire.

Letter, 1865

T OLSTOY: I do not believe my faith to be the one indubitable truth for all time, but I see no other that is plainer, clearer, or answers better to all the demands of my reason and my heart; should I find such a one I shall at once accept it. But I can no more return to that from which with such suffering I have escaped, than a flying bird can re-enter the egg shell from which it has emerged. He who begins by loving Christianity better than truth, will proceed by loving his own sect or church better than Christianity, and end in loving himself (his own peace) better than all, said Coleridge.

Reply to Edict of Excommunication

W ITTGENSTEIN: What is the use of studying philosophy if (See 10)

S ARTRE: If a writer has chosen to be silent (See 16)

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Stanley Corngold

In a disarmingly simple sentence in The Faith of a Heretic, Walter Kaufmann writes of the commitments made by two formidable men of letters, Hermann Hesse and Martin Buber: Their personalities qualify their ideas. Kaufmann means that such commitmentsHesses apolitical, quietist reclusiveness and Martin Bubers subjective principles of Bible translationmay not have the same value when accepted by men of a different character. Here we have the authors recurrent insistence on the exemplary importance of great personalities, if we are ever to learn the meaning of humanity. He might have quoted Stephen Spender: I think continually of those who were truly great. Shakespeare, Goethe, Nietzsche, and Freud are Kaufmanns distinctive examples. This high valuation of character over culturea character informed by what was once called virtwill, flooded with intelligencecould make Kaufmanns thoughts seem out of season in our acquisitive, culture-besotted age. But his distaste throughout the 1950s and 1960s for the feeling that the times could no longer countenance greatness of soul would have survived him into our century. His short life gives us a good, strong taste of what such greatness of soul would be like.

Kaufmann was born in 1921 in Freiburg, Germany, into a Protestant family with Jewish forebears. His heretical disposition was in evidence at a very early age. In a vivid interview, he recalls that he was unable to understand who or what the Holy He took this conclusion very seriously and, not yet twelve years old, formally abjured Christianity, asking forand receivingan official document that confirmed his decision.

His abjuration of Christianity was not an abjuration of religion, a subject that would occupy him for the rest of his life. It is the essential subject of The Faith of a Heretic. At twelve, he converted to Judaism, ignorant of the fact that all his grandparents were born Jewish. Thereafter, he intended to become a rabbi, a not-surprising impulse, he explains, since

in Germany at that time, there was nothing else to study. As a Jew I couldnt go to the university, so, being terribly interested in religion at that time, and in Judaism in particular, that was what I thought I would do.

Kaufmann immigrated to the United States in 1939, escaping the fate of several members of his family. Their change of faith meant nothing to the Nazis; the entire family, Walter Kaufmann included, could have expected certain death had they not left Germany. One of Walters uncles, fighting for the fatherland in the First World War, died in Russia; two others were murdered. The dedication to this volume reads:

To My Uncles

Walter Seligsohn

who volunteered in 1914 and was

shot off his horse on the Russian front in 1915

Julius Seligsohn

and

Franz Kaufmann

both Oberleutnant, Iron Cross, First-Class, 191418, one a devout Jew,

one a devout convert to Christianity,

one killed in a Nazi concentration camp in 1942,

one shot by the Secret Police in 1944,

both for gallantly helping others

in obedience to conscience, defiant

On arriving in the United States, Kaufmann enrolled at Williams College, where he majored in philosophy and religion. His likely path was to graduate school, to write a doctoral thesis in philosophy, but his ever-present will to action, and now with a war on, urged him, after a year at Harvard, to join the Army Air Force and thereafter the Military Intelligence Service. His experience with the occupying troops was morally vexing, and a poem in his volume Cain and Other Poems tells of his chagrin:

Occupation

Parading among a conquered and starving people

Next page