But with a sense of its current debasement in fashionable excesses of sensibility. The age of High Romanticism made the word a focus for hopes of revolution and social change in the future. It became a political term.

Instead of improbable notions and false sensibility, Romanticism came to stand for authenticity, integrity and spontaneity. It was seen as a positive artistic and intellectual assertion of the extremes in the human psyche, the areas of experience beyond logic and reason which could only be expressed in a direct and heartfelt way. These new concerns were seen as a valid response to the extremes of change and uncertainty which the age itself displayed.

A new term is needed to define qualities in the arts which have never been given such prominence before the free expression of imagination and association.

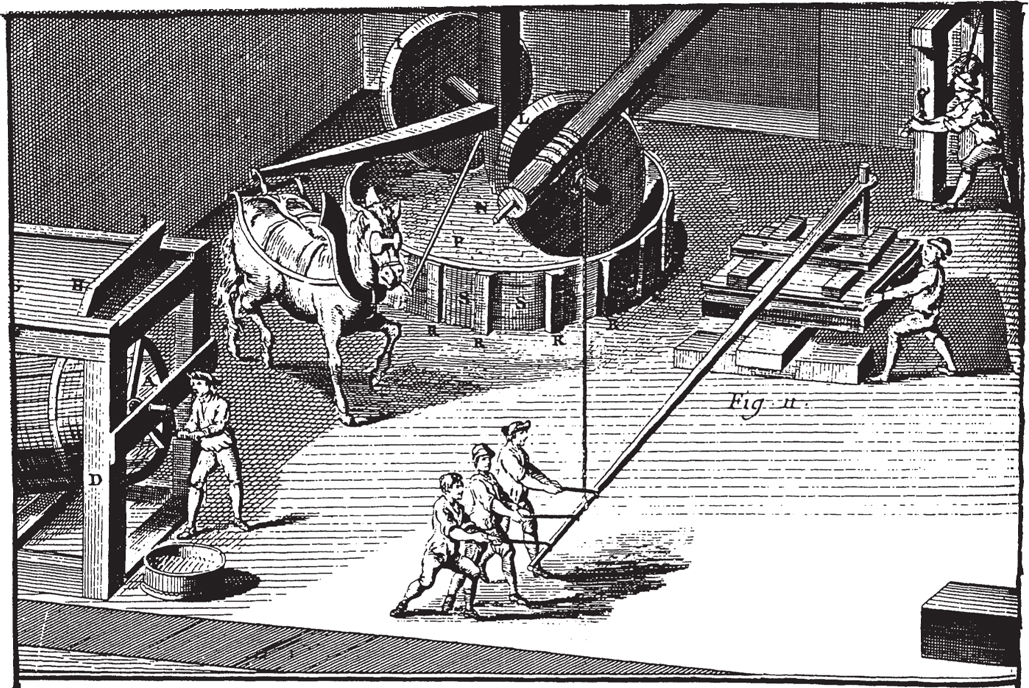

But what had happened in the forty years between Johnson and Schlegel to make such a difference in their attitudes? The Western world had been shaken by two political revolutions, in America (1776) and France (1789), and by an industrial revolution which was beginning to erode the traditionally agrarian lives of many people.

New ways of living had to be reflected in new ways of thinking. Romanticism, for want of any better word, came to stand for this new experience of the world. The true Romantic was not an over-sensitive dreamer, but a heroic figure facing head-on the painful realities of his time a figure of genius.

The Problem Child of the Enlightenment

To understand Romanticism, it is necessary first to understand the Enlightenment. As the problem child of this great movement, Romanticism shows many of the characteristics of its parent, but equally some radical differences.

The Enlightenment affected most of the Western world during the late 17th and 18th centuries. It was above all a movement which sought to emancipate mankind, regardless of political frontiers, from the triple tyranny of despotism, bigotry and superstition. What were the weapons in this fight?

The great advancement in learning which marks this age The possibility of a concerted intellectual movement Rationalism as the common language of science, philosophy and literature.

Momentous advances occurred in science, philosophy and politics. The discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton (16421727) confirmed the regular and ordered nature of the universe. The philosopher John Locke (16321704) asserted that only the information of the senses, experience and observation could provide true understanding of the external world. Scientific knowledge could banish superstition.

Universal Enlightenment

The aim of intellectuals was to cosmopolitanize their work and make inquiry an international activity which would shed light on the universal collective condition of man. The American and French Revolutions were given their intellectual basis by the common struggle for secular humanistic ideals which, in spite of their differences of opinion, united intellectuals across the Western world. The German philosopher Immanuel Kant was in no doubt about this

It is time to cast off mans immaturity through the action of the inquiring mind, even if the limits of possible knowledge are revealed in the process.

Philosophers, satirists, scientists, artists, politicians and intellectuals attempted to banish mans dependence on received wisdom and the authority of the Church in favour of a theory of existence in which man could stand unaided at the centre of his own rational universe.

Intellectual inquiry across the Western world was marked by a spirit of unity and self-confidence. The colossal Encyclopdie supervised by Denis Diderot (171384), a work which attempted to bring together the accumulated wisdom of the age using the talents of its foremost intellects, was the definitive product of the Enlightenment ethos.