Experience without theory is blind,

but theory without experience is mere intellectual play.

paraphrase of Immanuel Kant

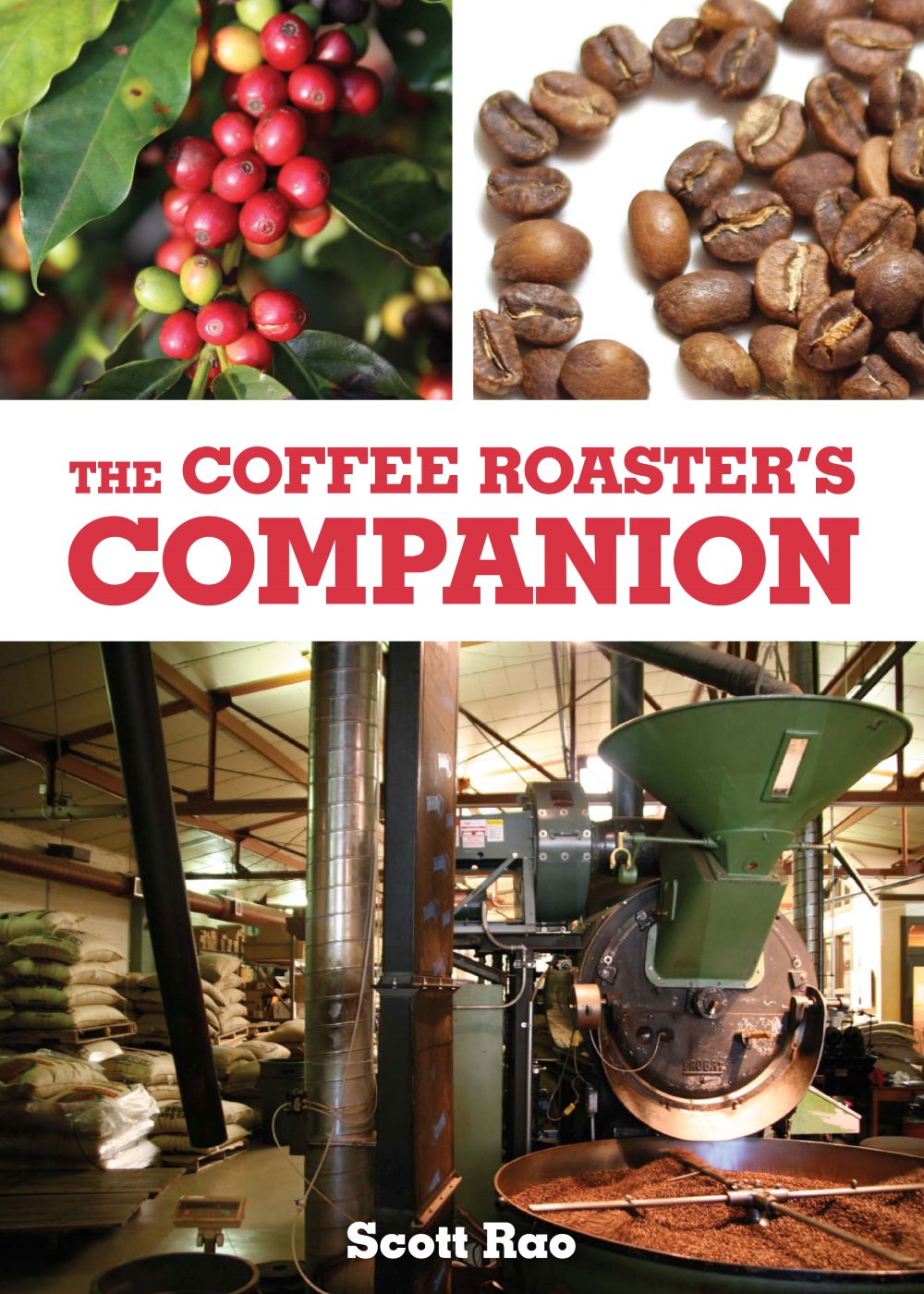

Liz Clayton and I thank Cafe Grumpy, Stone Street Coffee, Gillies Coffee Company, Pulley Collective, Intelligentsia Coffee, Irving Farm Coffee Roasters, and Dallis Bros. Coffee for graciously allowing her to photograph their roasting facilities for this book.

The author has taken care in preparation of this book but assumes no responsibility for errors or inaccuracies.

Copyright 2014 by Scott Rao

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

Printed in Canada.

ISBN 978-1-4951-1819-7

Text and graphics copyright 2014 by Scott Rao

Photographs copyright 2014 by Liz Clayton

Photography by Liz Clayton

Book design by Rebecca S. Neimark, Twenty-Six Letters

Please visit www.scottrao.com for information about purchasing this book.

Acknowledgments

Im grateful to several talented people for their help in creating this book. I would not have written a chapter on green coffee without Ryan Browns help. Ryans patient tutoring and vast knowledge of green coffee are responsible for most of the green-coffee information contained here.

Andy Schecter, Rich Nieto, Ian Levine, Mark Winick, Liz Clayton, and Vince Fedele provided valuable edits and feedback on the rst draft. Eric Svendson and Henry Schwartzberg generously offered their expertise on thermocouples. Liz Clayton created this books lovely photos and contributed insightful editorial feedback. Janine Aniko converted my amateur drawings into professional graphics.

Rebecca Neimark is responsible for this books handsome design and layout. Jean Zimmer, my editor and coach, cleaned up my cliche-laden prose and again made me look like a better writer than I am. I cant imagine publishing a book without those two.

James Marcottes brilliant roasting turned me into a coffee lover two decades ago and set a standard that few roasters have since met.

Preface

Coffee roasting has always been something of a dark art. Although people have been roasting coffee for hundreds of years, little prescriptive or scientic writing about roasting exists. At best, roasters learn their trade by apprenticing under an experienced, competent roaster. More commonly, young roasters learn by trial and error, roasting and tasting countless batches, and develop a system based on folklore and spurious reasoning.

I spent the rst ten years of my roasting career lost in the labyrinth of trial and error, and while I made some progress, it was usually of the two steps forward, one step back type. I desperately wanted a rational basis for my roasting beliefs, one that would prove itself in blind taste tests and apply to all beans and roasting machines.

After owning two roasting companies, I have had the good fortune to work as a consultant for many roasters. Through consulting I have had the opportunity to use many coffee-roasting machines and witness a variety of approaches to roasting and tasting. As part of my consulting work, I have often spent long hours analyzing roast data, trying to help my clients quantify their best practices. About six years ago I began to notice that the data of the rare, extraordinary batches all shared certain patterns, regardless of the bean or machine. Ive spent the past six years testing and rening those patterns; they form the foundation of the system I present in this book.

I dont claim to have all, or even most, of the answers. Despite my ignorance, I offer the ideas in this book to begin a long-overdue conversation about how to systematically roast coffee. Merely claiming that coffee roasting should be subjected to a systematic, objective, evidence-based approach is sure to offend some coffee professionals. Many roasters believe their special feel for roasting makes their coffee great. However, as recent technological advances have improved our ability to measure roast development and consistency, those intuitive roasters results have usually been found lacking.

With the introduction of data-logging software and the coffee refractometer, roasters have powerful new tools to track and measure results, making the process more predictable and consistent. I confess I miss the romance of making countless manual adjustments during a roast, furiously scribbling notes in a logbook, and running back and forth between the machine and logbook fty times per batch. Watching a roast proles progress on a computer screen lacks the Visceral satisfaction of the old methods. I dont roast for my own entertainment, however; I roast to give my customers the best-tasting coffee I can. On the rare occasion when I allow myself to sit quietly and enjoy a coffee, Im grateful for the results.

Introduction

This book is meant to be a reference for any roaster, whether a beginner or a professional. For our purposes, I will focus on light-to-medium roasting of specialty coffee processed in a batch drum roaster in 8-16 minutes. Most of what I will discuss also applies to continuous roasters, high-yield roasters, uid-bed roasters, and other roasting technologies. However, I will not often refer to such roasting machines directly.

I implore the reader to study this entire book and not focus solely on the how to chapters. Experience with my previous books has taught me that readers who cherry-pick the parts that appeal to them end up missing some of the big picture, leading them to misapply some recommendations. Ive italicized potentially unfamiliar terms throughout the text and dened them in the glossary at the end of the book.

1: Why We Roast Coffee Beans

Coffee beans are the seeds of the cherries of the coffee tree. Each cherry typically contains two beans whose at sides face each other. When steeped in hot water, raw, or green, coffee beans offer little in the way of what one might relate to as coffee taste and aroma.

Roasting green coffee creates myriad chemical changes, the production and breakdown of thousands of compounds, and, the roaster hopes, the development of beautiful avors when the beans are ground and steeped in hot water. Among its many effects, roasting causes beans to

- Change in color from green to yellow to tan to brown to black.

- Nearly double in size.

- Become half as dense.

- Gain, and then lose, sweetness.

- Become much more acidic.

- Develop upwards of 800 aroma compounds.

- Pop loudly as they release pressurized gases and water vapor.

The goal of roasting is to optimize the avors of coffees soluble chemistry. Dissolved solids make up brewed coffees taste, while dissolved volatile aromatic compounds and oils are responsible for aroma.

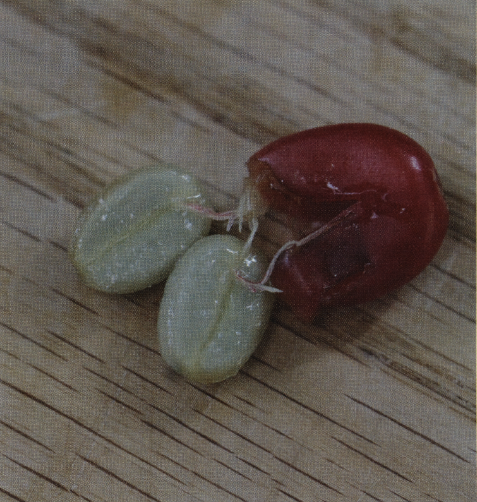

It's important to pick coffee cherries when ripe to maximize sweetness and acidity.

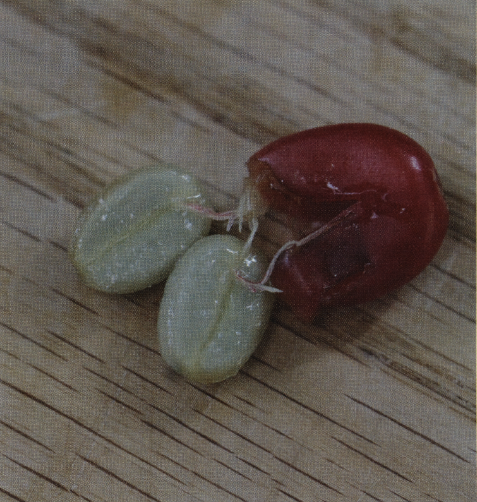

Coffee beans covered in mucilage from inside the cherry.

2: Green-Coffee Chemistry

Raw coffee beans are dense, green seeds consisting of about one-half carbohydrate in various forms and one-half a mixture of water, proteins, lipids, acids, and alkaloids. Roasters do not need to know much about green coffees chemistry to roast delicious coffee, but I offer the following summary to familiarize readers with the primary components of green coffee.

Next page