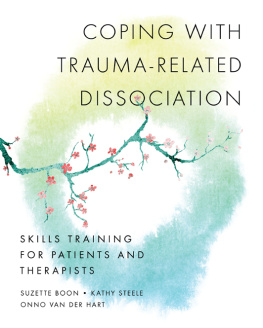

Coping With

Trauma-Related Dissociation

Skills Training for Patients

and Their Therapists

SUZETTE BOON

KATHY STEELE

ONNO VAN DER HART

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

New York London

A NORTON PROFESSIONAL BOOK

This e-book contains some places that ask the reader to fill in questions or comments. Please keep pen and paper handy as you read this e-book so that you can complete the exercises within.

To our patients, who have taught us much,

and are the true inspiration for this manual

CONTENTS

PART ONE

Understanding Dissociation and Trauma-Related Disorders

PART TWO

Initial Skills for Coping With Dissociation

PART THREE

Improving Daily Life

PART FOUR

Coping With Trauma-Related Triggers and Memories

PART FIVE

Understanding Emotions and Cognitions

PART SIX

Advanced Coping Skills

PART SEVEN

Improving Relationships With Others

PART EIGHT

Guide for Group Trainers

Coping With Trauma-Related Dissociation is the first manual developed for patients with complex developmental trauma disorders such as Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) and Dissociative Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (DDNOS). The treatment of complex dissociative disorders has gained increasing acceptance because these diagnoses have been validated across numerous populations, and treatment approaches based on expert clinical consensus have shown consistent and significant promise (for treatment guidelines, see International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation [ISSTD], in press). Studies to date, although methodologically flawed, indicate patients with a dissociative disorder benefit from treatment that specifically focuses on dissociative pathology, with two thirds showing improvements in a range of symptoms that include dissociation, anxiety, depression, general distress, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Brand, Classen, McNary, & Zaveri, 2009, p. 652). Preliminary efforts to empirically validate these treatments have shown positive results (Brand, Classen, Lanius, et al., 2009), and further research is underway.

In the 1990s, skills-training books for traumatized and other psychotherapy patients began to emerge, but none were specific for individuals with a complex dissociative disorder. Many focused on a particular theoretical approach or techniques for problems related to but not specific for trauma, and thus have become useful additions to the treatment of traumatized individuals in general. Some were intended as an adjunct to individual therapy or for personal use, whereas others were designed for structured group settings.

These valuable manuals cover a wide range of topics, including safety, emotional regulation and affect phobia, social anxiety, addictions, self-harm, depression, anxiety, and relationship issues. Some of the prominent ones that have been particularly useful for many trauma survivors include dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality (Linehan, 1993); systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving (STEPPS; Blum et al., 2008; Bos, Van Wel, Appelo, & Verbraak, 2010 also for borderline personality; short-term psychodynamic treatment of affect phobia (McCullough et al., 2003); and mindfulness and mentalization-based treatments such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Follette & Pistorello, 2007).

In the past decade, manuals that specifically address the treatment of trauma have emerged, a number of them empirically validated. Several are specific to PSTD, mostly based on cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and prolonged exposure (for example, Rothbaum, Foa, & Hembree, 2007; Williams & Poijula, 2002). Other PTSD manuals have integrated CBT with additional modalities, including emotion regulation (for example, Ford & Russo, 2006: trauma adaptive recovery group education and therapy [TARGET]; Wolfsdorf & Zlotnick, 2001; Zlotnick et al., 1997); interpersonal and case management for trauma and addictions (Seeking Safety, Najavits, 2002); and an eclectic approach Beyond Survival, Vermilyea, 2007). Cloitre, Cohen, and Koenen (2006) were the first to develop a psychotherapy manual specifically for complex PTSD in adult survivors of childhood abuse, based on CBT and attachment-interpersonal-object relations. In the Netherlands, a stabilization course for complex PTSD, Vroeger & Verder (Dorrepaal, Thomaes, & Draijer, 2008), was published, adapted from an original manual by C. Zlotnick et al., with some additional materials.

Some of these trauma-focused manuals are meant to specifically address the treatment of traumatic memories, but expert consensus indicates that patients with a complex dissociative disorder are at significant risk of being destabilized and may even decompensate when they are exposed prematurely to traumatic memories. The vast majority of these patients require a significant period of stabilization and skills building before they can successfully tolerate and integrate traumatic memories. In fact, the general clinical consensus for the treatment of chronically traumatized individuals, including patients with DID or DDNOS, is phase-oriented individual outpatient therapy, consisting of the following: (1) stabilization, symptom reduction, and skills training; (2) treatment of traumatic memories; and (3) personality integration and rehabilitation (Boon & Van der Hart, 1991; Brown, Scheflin, & Hammond, 1998; Chu, 1998; Courtois, 1999; Herman, 1992; ISSTD, in press; Kluft, 1999; Steele & Van der Hart, 2009; Steele, Van der Hart, & Nijenhuis, 2001, 2005; Van der Hart, Van der Kolk, & Boon, 1998; Van der Hart, Nijenhuis, & Steele, 2006).

The treatment guidelines for DID and DDNOS (ISSTD, 2011) and other publications by experts in the field provide an excellent overview of treatment approaches (for example, Kluft & Fine, 1993; Kluft, 1999, 2006; Putnam, 1989; 1997; Ross, 1989, 1997; Steele & Van der Hart, 2009; Van der Hart, Nijenhuis, & Steele, 2006). These publications also provide specific interventions. Nevertheless, therapists are still left to cull a hodgepodge of specific Phase I skills-based techniques from the literature and rich oral traditions of the field of dissociative disorders, leaving any given treatment at the mercy of the therapists creativity and familiarity with the literature. In this manual, we have attempted to gather fundamental Phase I stabilization techniques for patients and their therapists, specifically tailored to address the dissociation that underlies and maintains many of their symptoms. Some of these skills include mentalization; mindfulness; emotion and impulse regulation; inner empathy, communication, and cooperation; development of inner safety; and cognitive, affective, and relational skills.

At the heart of the manual is approximately 30 years of clinical experience that each of the authors has had with patients who have DID or DDNOS, coupled with the magnificent and foundational work of many other colleagues who are pioneers in the field. It is well known that clinical innovations come from clinicians, not researchers (Westen, Novotny, & Thompson-Brenner, 2004), and until sufficient randomized controlled studies have been conducted on treatment of complex dissociative disorders, we are reliant upon this hard-won clinical wisdom. For the first time, this manual provides an operationalized treatment protocol that is subject to empirical validation for this most-in-need population which has been excluded from other studies on trauma treatments.

Development of the Skills-Training Manual

This manual is partly based on ongoing learning experiences with outpatient day treatment programs for patients with DID in the past decade in The Netherlands. These day programs usually ran daily during the week for a half to a full day, and they included adjunctive therapies, such as art and movement therapy. This distinguished them from the more cognitively oriented courses for borderline personality disorder. The nonverbal, experiential components of these treatment programs proved to be particularly destabilizing for many patients with complex dissociative disorders in the early stages of treatment. These modalities can reactivate traumatic memories and dissociative parts, which results in disorganization of the person as a whole, especially when the phobia of inner experience remains intense. These difficulties led one of us (S. B.) to develop a manualized course of limited duration, comparable to skills training such as dialectical behavior therapy (Linehan, 1993) and STEPPS (Blum et al., 2008; Bos et al., 2010), but specifically designed for patients with complex dissociative disorders.

Next page