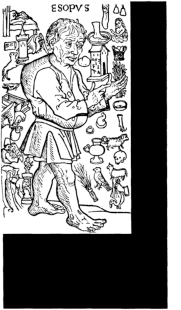

Introduction

It was prettily devised of Aesop; The fly sat upon the axle-tree of the chariot wheel, and said, What a dust do I raise?

Bacon: Of Vain-Glory

Quoting Sir Francis Bacon quoting Aesop quoting a fly, In fact, the fables use in elementary pedagogy was only one branch of the educational practice initiated by the Renaissance humanists who recovered the great texts of classical antiquity and made them the staples of early modern philology and rhetoric. And long after the boys of the sixteenth century had been taught what they could learn from the fable as a formgrammar, the essentials of narrative fiction, the relation between moral and exemplarthey were reading and rewriting fables for their adult sagacity and cogent, real-world applicability.

This book describes the Aesopian fable as a hitherto underestimated function in Renaissance culture and subsequently. Partly thanks to their traditions of originhow fables came to be written, by whom, and whytraditions which (whether or not they believed them) were deeply interesting to sixteenth- and seventeenth-century readers, the stories of the beasts, the birds, the trees, and the insects quickly acquired or recovered their function as a medium of political analysis and communication, especially in the form of a communication from or on behalf of the politically powerless. As Lydgate had put it for the late middle ages:

Of many straunge uncouthe simylitude,

Poetis of olde fablis have contryvid,

Of Sheep, of Hors, of Gees, of bestis rude,

By which ther wittis wer secretly apprevid,

Undir covert [termes] tyrantis eeke reprevid

Ther oppressiouns & malis to chastise

By examplis of resoun to be mevid,

For no prerogatiff poore folk to despise.

In England the tradition of political fabling was well established by the end of the fourteenth century, when Lydgate, it is thought, produced his own selection from Aesop and several non-Aesopian fables. Arnold Henderson has traced an increasingly explicit tradition of social commentary in the fable from the twelfth century through the fifteenth, culminating in those of Robert Henryson. Not coincidentally, the late fifteenth century, with its terrible history of baronial strife, also produced one of the most famous editions of Aesop in England, William Caxtons translation of the French version of Steinhwel, which Caxton carefully dated as being finished in the fyrst yere of the regne of kyng Rychard the thyrdde. But the period of the fables greatest significance was approximately the one hundred and fifty years from the last quarter of Elizabeths reign through the first quarter of the eighteenth century; a long historical moment whose pivot was, of course, the English civil war, which not only provided one of the strongest motivations for the discovery and development of new forms of analysis, or for making old forms perform new tricks, but established for at least the next half century a structure of opposed political values, along with a supporting symbolic vocabulary. In the last quarter of the seventeenth century, and particularly in the wake of the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688, there developed what one might reasonably call a craze for political fables, whose modishness was eventually recognized by Aesops personal transformation into a fashionable man about town.

At least for the purpose of this inquiry, it is important to distinguish the fable in the strict sense from parables, or even, more loosely, fictions. Yet the Aesopian tradition did acquire additional authority from the fact that fables, as distinct from parables, occasionally occur in scripture. Significantly, biblical (or apocryphal) fables also carry a strong political valence. In 2 Esdras 4:1318 we are told that the angel Uriel illustrated the proper limits to human understanding by a cosmic fable:

I came to a forest in the plain where the trees held a counsel, And said, Come, let us go fight against the sea, that it may give place to us, and that we may make us more woods. Likewise the floods of the sea took counsel and said, Come, let us go up and fight against the trees of the wood, that we may get another country for us. But the purpose of the wood was vain: for the fire came and consumed it. Likewise also the purpose of the floods of the sea; for the sand stood up and stopped them.

This early indictment of militant expansionism could clearly also be used in conservative political arguments; but a far more powerful model appeared in Judges 9:815, where Jotham reproached the Israelites for having made Abimelech their king. Somewhat comically, Jotham describes this event as a failed system of political nomination, whereby only the last and least qualified candidate will accept the position:

The trees went forth on a time to anoint a king over them; and they said to the olive tree, Reign thou over us. But the olive tree said unto them, Should I leave my fatness, wherewith by me they honour God and man, and go to be promoted over the trees? And the trees said to the fig tree, Come thou, and reign over us. But the fig tree said unto them, Should I forsake my sweetness, and my good fruit, and go to be promoted over the trees? Then said the trees unto the vine, Come thou, and reign over us. And the vine said unto them, Should I leave my wine, which cheereth God and man, and go to be promoted over the trees? Then said all the trees unto the bramble, Come thou, and reign over us. And the bramble said unto the trees, If in truth ye anoint me king over you, then come and put your trust in my shadow; and if not, let fire come out of the bramble, and devour the cedars of Lebanon.

As a threatening contrast between two types of government, and one that questioned the wisdom of the plebiscite, Jothams clever narrative sponsored a whole series of tree fables in the seventeenth century, when the origins and sanctions of monarchy were being publicly debated, and became in its own right a common-place of republican theory.